Olympic Lifting for the College Football Player

Olympic weightlifting has long been used in numerous American football organizations to increase athletic performance. The University of Minnesota is no different. We utilize a wide variation of the Olympic movements to further enhance football performance.

First, let’s take a look at how the two events are similar; the average football play lasts about five seconds and is performed at a very high speed with large amounts of strength necessary to overcome one’s opponent. At the college level, there is a 40 second play clock before the next snap must occur, not accounting for timeouts.

Across the multiple positions, football is considered to be 90% Anaerobic and 10% glycolytic/intermediate energy system pathway. Weightlifting, in comparison, is performed at 100% of the anaerobic pathway. Not many sports other than certain field events in track and field (shot put, discus) are performed at intensity this high.

Along the same lines, both football and weightlifting are dependent on ground force application. If you refer to Newton’s 3 law of motion, you’ll know that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. With consideration to these two events, the harder you push into the ground, the more force you will be able to produce. A common phrase used among our staff is “the harder you push into the ground, the faster you run and higher you jump.” The game of football is played with athletes’ feet on the ground; therefore, it is vital to train with feet on the ground. The kinetic chain of power utilized to clean or snatch a heavy load is the very same chain utilized to propel one’s body in a given direction.

In addition, the motor skill development of weightlifting carries over to myriad other skills. The greatest lifters in the world are not necessarily stronger than others, but rather, much more technically sound. The ability to contract and relax the muscles of elite Olympic weightlifters is second to none. Football, being a game of trying to outmaneuver one’s opponent by multiple techniques, makes this contraction/relaxation ability a great asset to being able to utilize said different techniques to dominate one’s opponent.

How Olympic Lifting Is Programmed at the University of Minnesota

Our objective as strength and conditioning coaches for football is to create the best football player we can. It’s not to make elite Olympic weightlifters. If our goal was to create elite weightlifters, we would only use the full movements. With that being said, it is important to understand how we utilize the partial movements of the Clean & Jerk and the Snatch. A football player must be able to produce force at different body angles and also receive force at different angles.

Terminology

Clean: pulled from the floor, caught in a full front squat

Hang Clean: begins from hang position (standing position, bar at hips), caught in full front squat

Hang Power Clean: begins from the hang position, caught in “power position” (1/4 squat)

Power Clean: pulled from the floor, caught in “power position”

Block Power Clean: pulled from boxes with bar just below or just above knee, caught in “power position”

Block Clean: pulled from boxes with bar just below or above knee, caught in full front squat.

The Snatch variations are listed as the same, trading clean for snatch and bar is caught above the head in a full squat or “power position.”

Teaching Progression

The snatch is the first full movement taught to our new players. We believe that the snatch is easier to learn once the fundamentals of the RDL/hip hinge, triple extension, and high pull have been established. With that being said, before either the snatch or clean, the athletes are taken through a progression that breaks down the movement into the above sequence.

Foot Placement – Feet should start in one’s jumping stance, that is to say, feet underneath the hips.

Grip – We use the hook grip.

RDL – Knees are slightly bent, and athletes hinge at hips, pushing their butt back, loading their hamstrings and heels.

Triple Extension – Body weight transfers from heels to the balls of feet, and hips/knees/ankles simultaneously extend, bringing the athlete to tallest position possible.

High Pull – The explosive triple extension propels the bar upwards; the arms simply guide the bar up in close proximity to the body. Elbows remain above the wrists.

Catch – either snatch or clean catch.

The hook grip, RDL, Triple Extension, and High Pull are all taught as part of a complex during the first four to six weeks of a new athlete’s training program.

For example: 6x RDL, 6x Triple Extension/Shrug, 6x High Pull, 6x Front Squat.

As you can see, the front squat is being taught in concert with the other movements, thus making a smooth transition to the clean catch once proper bar and body position has been established.

Simultaneously, on a different training day, the overhead press is taught in progression from a strict military press, to push press, to push jerk. This enforces proper bar placement overhead. We call it the “sweet spot;” the position overhead with the elbows locked dispersing the load of the bar throughout the entire body. Note that all presses are taught from the front rack position (front squat catch).

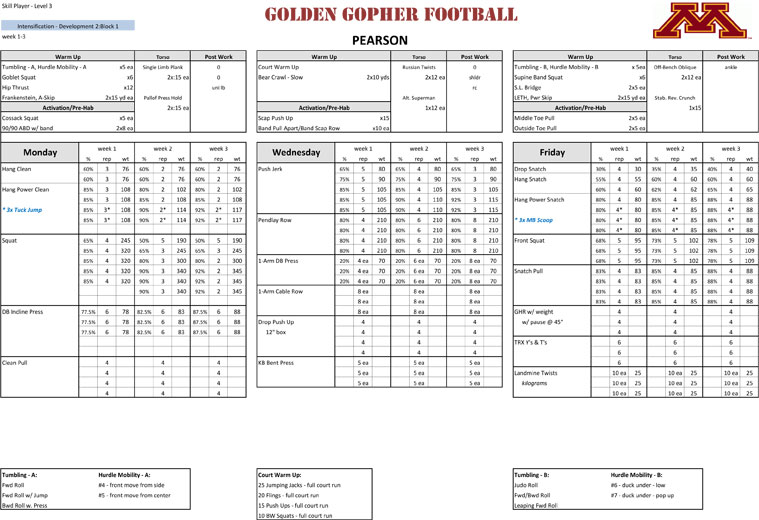

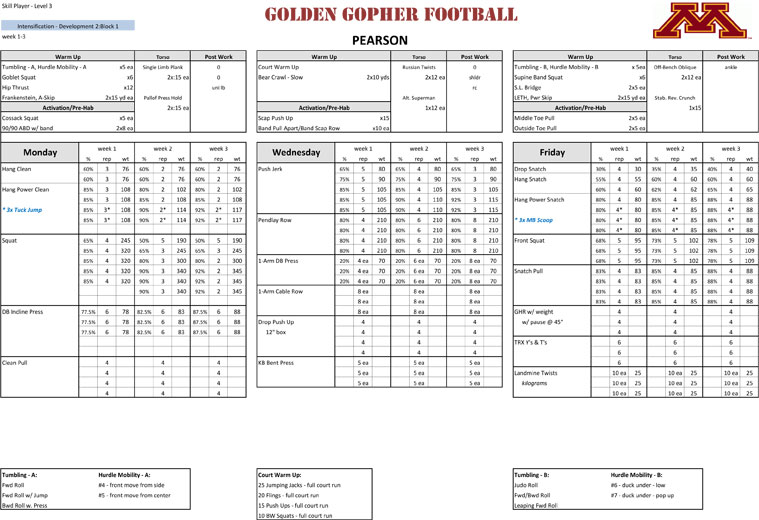

Positional Differences: The strength and conditioning program at the University of Minnesota is designed to progress the athlete for a full four years. As the athlete enters as a freshman in the summer or as a junior college transfer, they enter what we call Block Zero, similar to that of Coach Joe Kenn during his tenure at the University of Louisville. This is a phase of training where the teaching progressions take place. The importance is placed on quality of the movements rather than quantity. There is no interest in how heavily the athlete can lift a weight incorrectly. Further, the athletes will progress another 4 levels with the next level beginning in January. After the athlete finishes Block Zero and enters Level 1, they will be split into a Front-7 group (offensive line, tight ends, defensive line, linebackers, long snappers), or a Skill group (wide receivers, running backs, defensive backs, kickers, punters), or a Quarterback group.

The differences in these levels are subtle, as the main priority of each training day is the same. However, a basic understanding of the positional needs is met. A Front-7 player will begin each play from a static position and usually with a hand on the ground, especially the offensive and defensive linemen. Therefore, a majority of the Olympic movements performed will begin with the bar on the floor to emulate the static position to begin each play. A Skill player will commonly be in a more athletic position, often moving before the snap of the ball. Therefore, a majority of the movements are performed from a hang position. Rep/set schemes are very similar during individual phases of the year (in-season, winter, spring, summer), but commonly change between each one. The highest number of reps in a set is limited to six and often in the 3-5 rep range. In order to increase total volume, more sets are added to accomplish the desired training effect at the prescribed load.

It is understood that the security of a strength and conditioning coach is limited to the success of the football team. Therefore, it is vital that we are able to produce the best possible athlete in the safest possible way. Having a star player on the sidelines with an injury due to poor training (barring any freak injury) is a strength coach’s worst nightmare. By utilizing the Olympic weightlifting movements to increase ground force production, motor skill development--and in conjunction with the athletes current speed training/conditioning phase--it is our desire that these athletic abilities will transfer to the football field, enabling the athlete to utilize their skills to become a great football player.

References:

Arthur, Michael; Bailey, Bryan. Complete Conditioning for Football. Champaign, Ill: 1998. Human Kinetics

Siff, Mel C. Supertraining. Denver, Co: 2003. Supertraining Institute

First, let’s take a look at how the two events are similar; the average football play lasts about five seconds and is performed at a very high speed with large amounts of strength necessary to overcome one’s opponent. At the college level, there is a 40 second play clock before the next snap must occur, not accounting for timeouts.

Across the multiple positions, football is considered to be 90% Anaerobic and 10% glycolytic/intermediate energy system pathway. Weightlifting, in comparison, is performed at 100% of the anaerobic pathway. Not many sports other than certain field events in track and field (shot put, discus) are performed at intensity this high.

Along the same lines, both football and weightlifting are dependent on ground force application. If you refer to Newton’s 3 law of motion, you’ll know that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. With consideration to these two events, the harder you push into the ground, the more force you will be able to produce. A common phrase used among our staff is “the harder you push into the ground, the faster you run and higher you jump.” The game of football is played with athletes’ feet on the ground; therefore, it is vital to train with feet on the ground. The kinetic chain of power utilized to clean or snatch a heavy load is the very same chain utilized to propel one’s body in a given direction.

In addition, the motor skill development of weightlifting carries over to myriad other skills. The greatest lifters in the world are not necessarily stronger than others, but rather, much more technically sound. The ability to contract and relax the muscles of elite Olympic weightlifters is second to none. Football, being a game of trying to outmaneuver one’s opponent by multiple techniques, makes this contraction/relaxation ability a great asset to being able to utilize said different techniques to dominate one’s opponent.

How Olympic Lifting Is Programmed at the University of Minnesota

Our objective as strength and conditioning coaches for football is to create the best football player we can. It’s not to make elite Olympic weightlifters. If our goal was to create elite weightlifters, we would only use the full movements. With that being said, it is important to understand how we utilize the partial movements of the Clean & Jerk and the Snatch. A football player must be able to produce force at different body angles and also receive force at different angles.

Terminology

Clean: pulled from the floor, caught in a full front squat

Hang Clean: begins from hang position (standing position, bar at hips), caught in full front squat

Hang Power Clean: begins from the hang position, caught in “power position” (1/4 squat)

Power Clean: pulled from the floor, caught in “power position”

Block Power Clean: pulled from boxes with bar just below or just above knee, caught in “power position”

Block Clean: pulled from boxes with bar just below or above knee, caught in full front squat.

The Snatch variations are listed as the same, trading clean for snatch and bar is caught above the head in a full squat or “power position.”

Teaching Progression

The snatch is the first full movement taught to our new players. We believe that the snatch is easier to learn once the fundamentals of the RDL/hip hinge, triple extension, and high pull have been established. With that being said, before either the snatch or clean, the athletes are taken through a progression that breaks down the movement into the above sequence.

Foot Placement – Feet should start in one’s jumping stance, that is to say, feet underneath the hips.

Grip – We use the hook grip.

RDL – Knees are slightly bent, and athletes hinge at hips, pushing their butt back, loading their hamstrings and heels.

Triple Extension – Body weight transfers from heels to the balls of feet, and hips/knees/ankles simultaneously extend, bringing the athlete to tallest position possible.

High Pull – The explosive triple extension propels the bar upwards; the arms simply guide the bar up in close proximity to the body. Elbows remain above the wrists.

Catch – either snatch or clean catch.

The hook grip, RDL, Triple Extension, and High Pull are all taught as part of a complex during the first four to six weeks of a new athlete’s training program.

For example: 6x RDL, 6x Triple Extension/Shrug, 6x High Pull, 6x Front Squat.

As you can see, the front squat is being taught in concert with the other movements, thus making a smooth transition to the clean catch once proper bar and body position has been established.

Simultaneously, on a different training day, the overhead press is taught in progression from a strict military press, to push press, to push jerk. This enforces proper bar placement overhead. We call it the “sweet spot;” the position overhead with the elbows locked dispersing the load of the bar throughout the entire body. Note that all presses are taught from the front rack position (front squat catch).

Positional Differences: The strength and conditioning program at the University of Minnesota is designed to progress the athlete for a full four years. As the athlete enters as a freshman in the summer or as a junior college transfer, they enter what we call Block Zero, similar to that of Coach Joe Kenn during his tenure at the University of Louisville. This is a phase of training where the teaching progressions take place. The importance is placed on quality of the movements rather than quantity. There is no interest in how heavily the athlete can lift a weight incorrectly. Further, the athletes will progress another 4 levels with the next level beginning in January. After the athlete finishes Block Zero and enters Level 1, they will be split into a Front-7 group (offensive line, tight ends, defensive line, linebackers, long snappers), or a Skill group (wide receivers, running backs, defensive backs, kickers, punters), or a Quarterback group.

The differences in these levels are subtle, as the main priority of each training day is the same. However, a basic understanding of the positional needs is met. A Front-7 player will begin each play from a static position and usually with a hand on the ground, especially the offensive and defensive linemen. Therefore, a majority of the Olympic movements performed will begin with the bar on the floor to emulate the static position to begin each play. A Skill player will commonly be in a more athletic position, often moving before the snap of the ball. Therefore, a majority of the movements are performed from a hang position. Rep/set schemes are very similar during individual phases of the year (in-season, winter, spring, summer), but commonly change between each one. The highest number of reps in a set is limited to six and often in the 3-5 rep range. In order to increase total volume, more sets are added to accomplish the desired training effect at the prescribed load.

It is understood that the security of a strength and conditioning coach is limited to the success of the football team. Therefore, it is vital that we are able to produce the best possible athlete in the safest possible way. Having a star player on the sidelines with an injury due to poor training (barring any freak injury) is a strength coach’s worst nightmare. By utilizing the Olympic weightlifting movements to increase ground force production, motor skill development--and in conjunction with the athletes current speed training/conditioning phase--it is our desire that these athletic abilities will transfer to the football field, enabling the athlete to utilize their skills to become a great football player.

References:

Arthur, Michael; Bailey, Bryan. Complete Conditioning for Football. Champaign, Ill: 1998. Human Kinetics

Siff, Mel C. Supertraining. Denver, Co: 2003. Supertraining Institute

|

Chad Pearson is the Assistant Director of Strength and Conditioning coach for the University of Minnesota Football program, where he’s been working since December 2010. Pearson came to Minnesota after three years as an Assistant Sports Performance Coach at Northern Illinois University. In his three years at NIU, Pearson worked primarily with football players, baseball and softball players and wrestlers. He earned his master's degree in Kinesiology from Southern Illinois University in 2009. He is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA, and a USAW Sports erformance Coach. A former two-sport collegiate athlete, Pearson currently trains and competes in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date