Body Mechanics for Grappling: Pivoting and Pressure

The grappling arts, whether for sport or self defense, have been greatly popularized since the advent of the Ultimate Fighting Championship and other mixed martial arts events. While the technical emphasis of Judo, Sambo, wrestling, and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu may differ, they all rely on the essential principles of space, weight, leverage, and timing, and are becoming increasingly intermixed in this era of cross-training. For the sake of simplicity, I will use Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu terminology and methodology to explain two critical body mechanics for grappling: pivoting and pressure.

Pivoting

One objective of BJJ practice is to rehearse methods of moving on the ground that eliminate as much friction as possible. This allows for fluid movement, even with gravity working against you. In a live situation, your bodyweight and the bodyweight of your opponent work against you if your back is flat on the mat. A flat back has a large surface area, which means too much friction for free movement.

It is imperative for grapplers to develop mechanisms that allow them to generate space when necessary—but just enough space to implement their techniques. Generating excessive space not only wastes energy, but it may allow your opponent to improve their position as both players scramble for control. If you are in a drastically inferior position, a return to your knees or to standing may be a large improvement (and relief!), but then the process of establishing grips and capturing your opponent's center begins all over again. Strategically, the pivot allows you to create just enough space to more favorably position yourself to regain guard, escape sidemount, or break down posture, eventually leading to a sweep or submission.

Pivoting can be done with several body parts, including the head, hands, elbows, shoulders, knees, and ball of the foot. Beginning students can improve their ability to transfer weight smoothly between their limbs by doing a simple counterbalancing exercise.

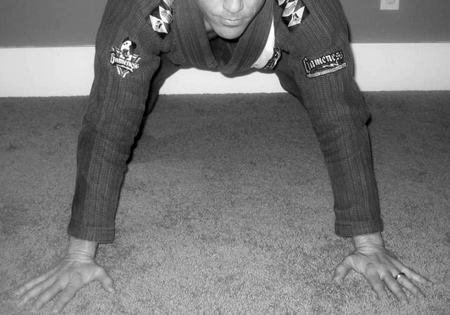

Start on all fours, knees slightly bent, on your toes.

Lift your left foot and right hand off of the ground, swinging your left foot underneath your right leg, while bringing your right hand over your right leg. Try to work slowly and smoothly, and feel the large degree of counterbalancing employed during the swapping of hand and foot positions. Reverse motions to the original position, then work the opposite side.

Intermediate and advanced students can begin pivoting off of other body parts, especially the elbow.

Shoulder pivoting is often easier to practice from a bridge,

Then drop your foot underneath your leg to go to your knees. If these movements are practiced smoothly, this pivot will become reflexive, and escaping sidemount by going to your knees will become second nature.

In a grappling match, the fight is largely over space, eliminating it or creating it, stifling or allowing movements. In a live situation, it is difficult to create all the space you would like, so pivoting is a method of movement that helps to position yourself for maximum leverage with minimal space.

Pressure

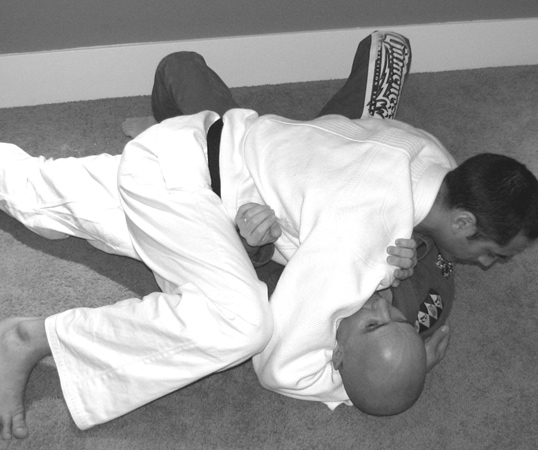

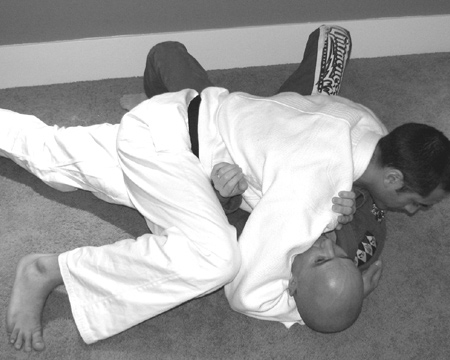

Offensively, the goal of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is to cut off angles and eliminate space. Starting from a standing position, a jiu jitsu player may lower his center of gravity, explosively shoot in on his opponent with a double leg takedown from wrestling, and end up in sidemount. By closing the gap between the two participants, the space is now controlled, and the angles of rear movement are no longer available to the person with his back on the ground. Plus that person is fighting gravity and the body weight of his opponent.

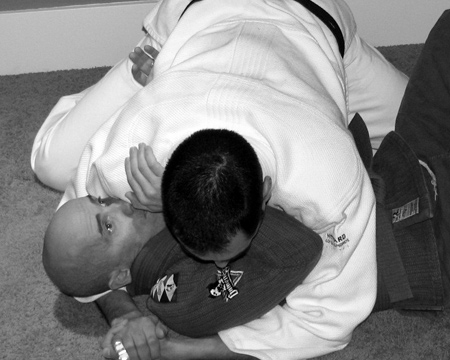

This is a solid sidemount position. Knees and elbows tight to his body—I am framing him in. I have eliminated most of the space between us; however, I can go further and create pressure in how I hold Jimmy. Pressure is the use of bodyweight, angles, and isometric strength to go beyond the reduction of space between bodies to the point of invasively compressing your opponent. Not only can they not move, they can't breathe. The first step in creating such pressure is cupping underneath the back:

Lift your opponent's shoulder up off the ground with the hand underneath their armpit, then replace with the hand running underneath their neck. Reinforce with your other hand and you are now able to use your back muscles to pull your weight into your opponent while pushing your chest forward.

I can further increase the strain on my opponent by making him support my entire bodyweight.

Note that I am not resting any weight on my knees or elbows, and am driving forward off of my toes. I angle my torso slightly, and drop my rear hip to block his knee from coming in. I can easily switch positions, bringing my left knee to his hip, and drive off of my right leg if the situation calls for it. My shoulder can also be used to turn his face away from me, making it extremely difficult for him to regain guard.

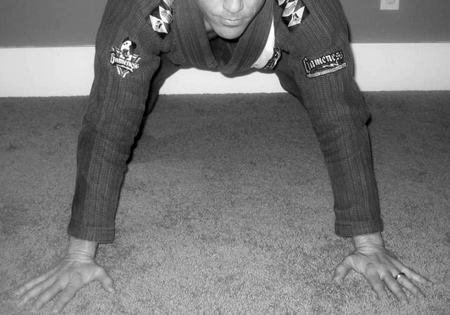

One helpful exercise for developing the isometric strength required for sustained pressure are low angle pushups. From a pushup position, drop down until your chest is a few inches off the floor. Lightly bounce here and feel the position. Alternate dropping shoulders, then eventually drop the same side hip and shoulder as your opposite knee comes up.

Work both sides, and feel for a momentary weight transfer to your hands while your legs quickly switch position.

Pressure is used in guard passing, immobilizations, chokes, and as incentive for your opponents to move and create an opening. Pivoting allows you to deflect or redirect the pressure and power aimed against you through movement and repositioning. Both are critical to developing a powerful and energy efficient grappling game, creating maximum leverage with minimal effort.

Pivoting

One objective of BJJ practice is to rehearse methods of moving on the ground that eliminate as much friction as possible. This allows for fluid movement, even with gravity working against you. In a live situation, your bodyweight and the bodyweight of your opponent work against you if your back is flat on the mat. A flat back has a large surface area, which means too much friction for free movement.

It is imperative for grapplers to develop mechanisms that allow them to generate space when necessary—but just enough space to implement their techniques. Generating excessive space not only wastes energy, but it may allow your opponent to improve their position as both players scramble for control. If you are in a drastically inferior position, a return to your knees or to standing may be a large improvement (and relief!), but then the process of establishing grips and capturing your opponent's center begins all over again. Strategically, the pivot allows you to create just enough space to more favorably position yourself to regain guard, escape sidemount, or break down posture, eventually leading to a sweep or submission.

Pivoting can be done with several body parts, including the head, hands, elbows, shoulders, knees, and ball of the foot. Beginning students can improve their ability to transfer weight smoothly between their limbs by doing a simple counterbalancing exercise.

Start on all fours, knees slightly bent, on your toes.

Lift your left foot and right hand off of the ground, swinging your left foot underneath your right leg, while bringing your right hand over your right leg. Try to work slowly and smoothly, and feel the large degree of counterbalancing employed during the swapping of hand and foot positions. Reverse motions to the original position, then work the opposite side.

Intermediate and advanced students can begin pivoting off of other body parts, especially the elbow.

Shoulder pivoting is often easier to practice from a bridge,

Then drop your foot underneath your leg to go to your knees. If these movements are practiced smoothly, this pivot will become reflexive, and escaping sidemount by going to your knees will become second nature.

In a grappling match, the fight is largely over space, eliminating it or creating it, stifling or allowing movements. In a live situation, it is difficult to create all the space you would like, so pivoting is a method of movement that helps to position yourself for maximum leverage with minimal space.

Pressure

Offensively, the goal of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is to cut off angles and eliminate space. Starting from a standing position, a jiu jitsu player may lower his center of gravity, explosively shoot in on his opponent with a double leg takedown from wrestling, and end up in sidemount. By closing the gap between the two participants, the space is now controlled, and the angles of rear movement are no longer available to the person with his back on the ground. Plus that person is fighting gravity and the body weight of his opponent.

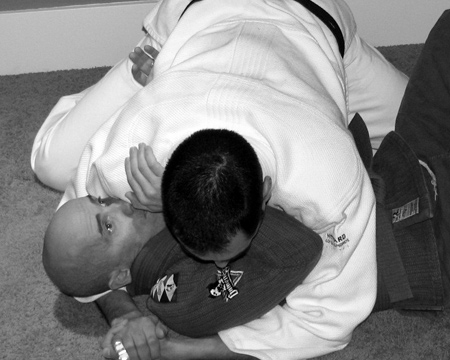

This is a solid sidemount position. Knees and elbows tight to his body—I am framing him in. I have eliminated most of the space between us; however, I can go further and create pressure in how I hold Jimmy. Pressure is the use of bodyweight, angles, and isometric strength to go beyond the reduction of space between bodies to the point of invasively compressing your opponent. Not only can they not move, they can't breathe. The first step in creating such pressure is cupping underneath the back:

Lift your opponent's shoulder up off the ground with the hand underneath their armpit, then replace with the hand running underneath their neck. Reinforce with your other hand and you are now able to use your back muscles to pull your weight into your opponent while pushing your chest forward.

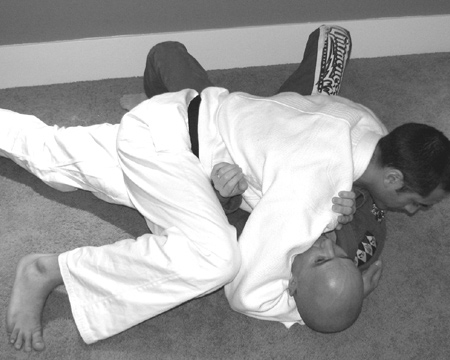

I can further increase the strain on my opponent by making him support my entire bodyweight.

Note that I am not resting any weight on my knees or elbows, and am driving forward off of my toes. I angle my torso slightly, and drop my rear hip to block his knee from coming in. I can easily switch positions, bringing my left knee to his hip, and drive off of my right leg if the situation calls for it. My shoulder can also be used to turn his face away from me, making it extremely difficult for him to regain guard.

One helpful exercise for developing the isometric strength required for sustained pressure are low angle pushups. From a pushup position, drop down until your chest is a few inches off the floor. Lightly bounce here and feel the position. Alternate dropping shoulders, then eventually drop the same side hip and shoulder as your opposite knee comes up.

Work both sides, and feel for a momentary weight transfer to your hands while your legs quickly switch position.

Pressure is used in guard passing, immobilizations, chokes, and as incentive for your opponents to move and create an opening. Pivoting allows you to deflect or redirect the pressure and power aimed against you through movement and repositioning. Both are critical to developing a powerful and energy efficient grappling game, creating maximum leverage with minimal effort.

|

Roy Dean has continuously studied martial arts since receiving his first degree black belt in Kodokan Judo at age 17. Dedicating himself to grappling arts, by age 24 he had also earned black belts in Aikikai Aikido and Seibukan Jujutsu, as well as a blue belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu under Claudio Franca. Moving to San Diego, Dean focused exclusively on the study of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu under Professor Roy Harris, receiving the prestigious black belt in 2006. Dean has won Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and submission grappling tournaments, and seeks to teach the refined art of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu at his Academy in Bend, Oregon. www.roydeanacademy.com |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date