True or False: Fascial Release Techniques Break Up Adhesions

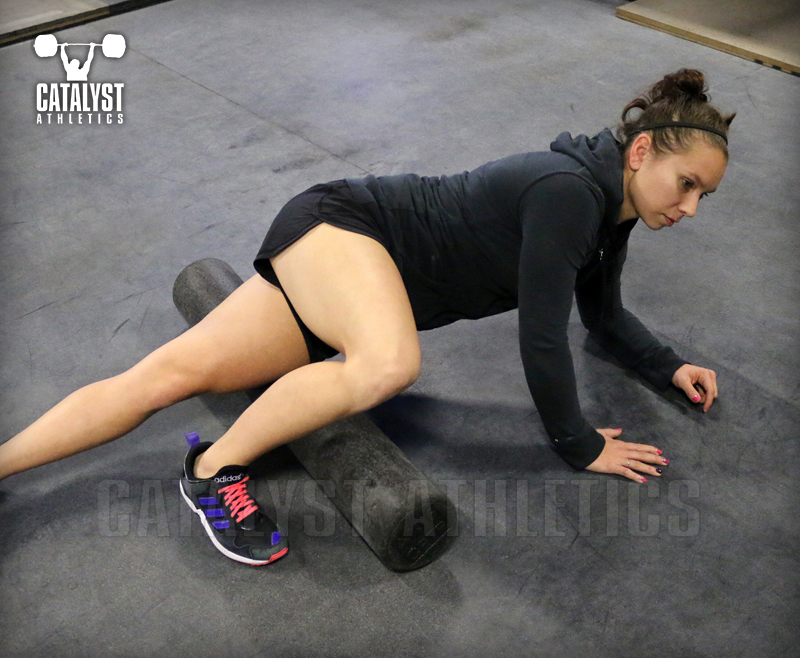

Some manual therapists talk a lot about fascia, and explain how their techniques will help to release or stretch your fascia and break up adhesions or scar tissue. They might talk about fascial release or myofascial release, or active release therapy, or you might see products such as foam rollers that promise to help you release your own fascia. In today’s column, we’ll look at what fascia is, and whether these claims hold water.

What is fascia?

Fascia is the name given to the sheets of connective tissue that separate or enclose muscles, internal organs within the body. If you’re a meat eater, think of the silvery film that you find when you cut into your chunk of meat, or the chewy gristle in a tough piece of steak. It comes in different layers, and is made up of similar components to tendons and ligaments. Much has been made of the fact that there is a web of fascia running through your body and connecting everything together.

Physical therapists often point out, quite rightly, that there is much that science doesn’t understand about fascia, and that it’s an ongoing area of research. There are conferences and societies that have been set up, dedicated to promoting and discussing fascia science, and in amongst all of this there is a lot of very interesting biology. But the important question is whether any of it is at all relevant to the treatments that fascia enthusiasts are promoting.

As massage therapist turned debunker of alternative health myths Paul Ingram points out on his website, “In the history of science and medicine, knowledge gaps get filled with guesses, and the guesses usually turn out to be wrong. Exotic biology is rarely useful biology. Interesting, but not useful. No one can get safe, effective, reliable treatment protocols out of barely understood biology. If you could, the biology wouldn’t be poorly understood anymore — and you’d be famous for pushing back the frontiers of human knowledge and reducing human suffering.”

Can we “release” fascia?

It seems increasingly unlikely. Fascia is an incredibly tough, dense material, almost as strong as steel according to some tests. Studies have shown that it’s pretty hard to stretch it much, if at all.

Some therapists point out that studies looking at fascia in the laboratory - whether from cadavers, or from pieces that have been removed as part of surgery - doesn’t necessarily tell us how it behaves in a living body. There are numerous nerve endings in the fascia, and we know that cells within the fascia can respond to certain kinds of mechanical stress over time, for example by stimulating cells to produce more collagen fibers in response to repeated weight bearing exercise for example. However, although research is ongoing, there appears to be little evidence at present for claims that this responsiveness to mechanical loading may provide a plausible mechanism for fascial release techniques in the clinic, which involve smaller forces over shorter time frames.

Does that mean these therapies don’t work?

Not quite so fast. What it means is that many of them don’t work the way that they claim to work. That doesn’t mean they’re not having an effect, though. If you enjoy having your body worked on and feel better afterwards, then there are some more plausible explanations for why that might be the case. Many therapists nowadays are starting to think and talk more in terms of pain science, and the effect that their treatment has on the nervous system, instead of focusing on changing the tissues under their fingers.

A review article by Robert Schleip written in 2003 casts doubt on the mechanical explanations of fascial release, and suggests an alternative mechanism for the reported effects of hands on treatment that’s centered around the effect that manual therapy has on the nervous system. This is more consistent with what we’re starting to understand about pain science, and there is a new wave of manual therapists (for example, Greg Lehman) who are beginning to talk about this as an updated model for what they do.

Studies that examine whether myofascial release techniques are actually effective are thin on the ground, however, and suffer from many of the difficulties associated with research on manual and manipulative therapies (small sample sizes, difficulty in finding an appropriate control condition, consistency of technique from one therapist to another, amongst others).

The verdict

Probably false. There is much that isn’t fully understood about fascia, but what we do know makes look increasingly unlikely that manual therapy has much of a mechanical effect on it directly. But even though your manual therapist may not be breaking down scar tissue or releasing adhesions, that doesn’t necessarily mean that what they’re doing isn’t having a beneficial effect via a different mechanism. If you find it helpful, then the fact that it’s not working as advertised may not be a deal-breaker. If you can find an open minded practitioner who is up to date with the research and talks about what they’re doing in terms of pain science and the nervous system, so much the better!

What is fascia?

Fascia is the name given to the sheets of connective tissue that separate or enclose muscles, internal organs within the body. If you’re a meat eater, think of the silvery film that you find when you cut into your chunk of meat, or the chewy gristle in a tough piece of steak. It comes in different layers, and is made up of similar components to tendons and ligaments. Much has been made of the fact that there is a web of fascia running through your body and connecting everything together.

Physical therapists often point out, quite rightly, that there is much that science doesn’t understand about fascia, and that it’s an ongoing area of research. There are conferences and societies that have been set up, dedicated to promoting and discussing fascia science, and in amongst all of this there is a lot of very interesting biology. But the important question is whether any of it is at all relevant to the treatments that fascia enthusiasts are promoting.

As massage therapist turned debunker of alternative health myths Paul Ingram points out on his website, “In the history of science and medicine, knowledge gaps get filled with guesses, and the guesses usually turn out to be wrong. Exotic biology is rarely useful biology. Interesting, but not useful. No one can get safe, effective, reliable treatment protocols out of barely understood biology. If you could, the biology wouldn’t be poorly understood anymore — and you’d be famous for pushing back the frontiers of human knowledge and reducing human suffering.”

Can we “release” fascia?

It seems increasingly unlikely. Fascia is an incredibly tough, dense material, almost as strong as steel according to some tests. Studies have shown that it’s pretty hard to stretch it much, if at all.

Some therapists point out that studies looking at fascia in the laboratory - whether from cadavers, or from pieces that have been removed as part of surgery - doesn’t necessarily tell us how it behaves in a living body. There are numerous nerve endings in the fascia, and we know that cells within the fascia can respond to certain kinds of mechanical stress over time, for example by stimulating cells to produce more collagen fibers in response to repeated weight bearing exercise for example. However, although research is ongoing, there appears to be little evidence at present for claims that this responsiveness to mechanical loading may provide a plausible mechanism for fascial release techniques in the clinic, which involve smaller forces over shorter time frames.

Does that mean these therapies don’t work?

Not quite so fast. What it means is that many of them don’t work the way that they claim to work. That doesn’t mean they’re not having an effect, though. If you enjoy having your body worked on and feel better afterwards, then there are some more plausible explanations for why that might be the case. Many therapists nowadays are starting to think and talk more in terms of pain science, and the effect that their treatment has on the nervous system, instead of focusing on changing the tissues under their fingers.

A review article by Robert Schleip written in 2003 casts doubt on the mechanical explanations of fascial release, and suggests an alternative mechanism for the reported effects of hands on treatment that’s centered around the effect that manual therapy has on the nervous system. This is more consistent with what we’re starting to understand about pain science, and there is a new wave of manual therapists (for example, Greg Lehman) who are beginning to talk about this as an updated model for what they do.

Studies that examine whether myofascial release techniques are actually effective are thin on the ground, however, and suffer from many of the difficulties associated with research on manual and manipulative therapies (small sample sizes, difficulty in finding an appropriate control condition, consistency of technique from one therapist to another, amongst others).

The verdict

Probably false. There is much that isn’t fully understood about fascia, but what we do know makes look increasingly unlikely that manual therapy has much of a mechanical effect on it directly. But even though your manual therapist may not be breaking down scar tissue or releasing adhesions, that doesn’t necessarily mean that what they’re doing isn’t having a beneficial effect via a different mechanism. If you find it helpful, then the fact that it’s not working as advertised may not be a deal-breaker. If you can find an open minded practitioner who is up to date with the research and talks about what they’re doing in terms of pain science and the nervous system, so much the better!

| Rosi Sexton studied math at Cambridge University, and went on to do a PhD in theoretical computer science before realizing that she didn’t want to spend the rest of her life sat behind a desk, so she became a professional MMA fighter instead. Along the way, she developed an interest in sports injuries, qualified as an Osteopath (in the UK), and became the first British woman to fight in the UFC. She retired from active competition in 2014, and these days, she divides her time between fixing broken people, doing Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, climbing, writing, picking up heavy things, and taking her son to soccer practice. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date