Injury: Grieving and Getting Past It

Injuries. They happen to the best of us. Whether nagging or serious, injuries throw us off of our game in more ways than one. To not be able to train and compete in the sports we love is a major blow to not only our lifestyle, but also our mental health. It is a great loss to not be able to physically perform the training we do on a routine basis, and as with all losses, working your way through a grieving process is standard. For those of you who have suffered an injury or who are currently managing an injury-related hiatus, you have/will most likely weave your way through the five stages of grief. Though the road to recovery can seem daunting, understanding how we mentally process what has happened to us is the first step in healing.

Denial

“This isn’t happening to me.” “I can’t be hurt!” “The pain isn’t that bad.” Those of us who have been injured during the tenure of our athletic training have probably uttered at least one of these statements. Refusing to accept that we are no longer physically capable of cleaning the bar or executing a pull-up—whether temporarily or permanently—is pretty much a part of our competitive DNA. No one wants to admit that they are breakable. We train hard and we eat clean. We do everything we are supposed to do to remain in optimum shape. We are creatures of habit and dedication; we don’t have time for injury. These are all of the thoughts that rattle through our brains because accepting the reality of our new situation is too jarring to comprehend. Eventually, however, reality will set in, which is when we move through to the second stage.

Anger

You leave your doctor’s office infuriated. She’s just told you to completely halt all lifting for the next four weeks. Doesn’t she understand what this means to you? You sit at home, replaying the moments back that lead to that ill-fated fumble. You beat yourself up. You are sure that if you would have done this or that, then the injury wouldn’t have occurred. If you would’ve been more rested, if you would’ve warmed up more, if you would’ve lifted less weight and focused more on form, if you would’ve tried harder. Why didn’t you just try harder? Your emotions start to get the best of you, but you have no outlet for them because you can’t do the one thing you like to do when your emotions are getting the best of you. So how do you manage? You bargain.

Bargaining

In stage three, athletes will start to cut deals with themselves. In our minds, if we promise to do better next time, that fulfills some sort of cosmic healing shortcut that will trim time off of our recovery. You make a solemn oath to your coaches to always heed their advice, as if they have the power to grant your wishes on the spot. You swear a blood oath to yourself that you will work on mobility every day just as soon as your knee heals, then look down at it, waiting for the miracle to happen. But it doesn’t happen. The wishes, and the prayers, and the promises do not accelerate the recovery process, and this catapults you into stage four.

Depression

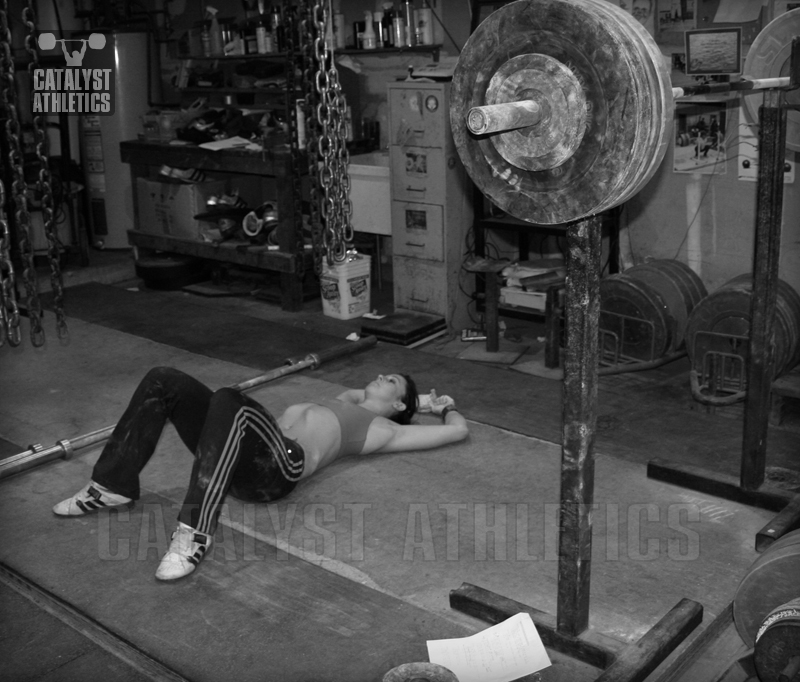

All hope is lost. You’re going to put on weight. You’re going to lose all of your strength. That hard work you’ve been putting in for the past six months is completely wasted. You might as well have never started training, because by the time you get back to it, you’ll be an out-of-shape slob who has completely forgotten what it’s like to do a bodyweight squat let alone a squat snatch. You can’t bring yourself to even drive by your gym. Seeing people – healthy people – walking through its doors cuts like a knife. “Do they even know how lucky they are,” you mumble under your breath. No. They don’t, and neither did you until it was too late. This is perhaps the hardest stage from which to pull ones self. Depending on the severity of the injury and the longevity of the recovery process, this stage can last weeks or months, perhaps even longer. Once through this dark time, however, you will find yourself in the last stage of the grieving process.

Acceptance

No matter how or when you arrive at this stage, something to keep in mind is that acceptance is not the same thing as feeling fine with your situation. Accepting your injury merely means you have accepted it as your reality. When—and only when—you have made it to stage five can you truly begin the mental healing process. You have finally reached the point where you can think and act on your recovery in a sensible manner, figuring out the next and best courses of action. Perhaps you schedule time to work with a physical therapist if you haven’t already. Maybe talking to a sports psychologist will help you get your head back in the game. Whatever it is that you decide, know that there is a light at the end of the proverbial tunnel. After all, you’ve made it this far.

Knowing, as they say, is half the battle. If you become injured, understanding the grieving process will help you to move through each phase with a little more ease. Be proactive: set up appointments with doctors and physical therapists to help you through this. Lay out a recovery game plan and a timeline you can physically check off. Keep track of your healing progress in a journal, which is also a great outlet for some of that stress and frustration you will undoubtedly feel. In short, tackle your recovery with the same tenacity that you tackle your training.

Denial

“This isn’t happening to me.” “I can’t be hurt!” “The pain isn’t that bad.” Those of us who have been injured during the tenure of our athletic training have probably uttered at least one of these statements. Refusing to accept that we are no longer physically capable of cleaning the bar or executing a pull-up—whether temporarily or permanently—is pretty much a part of our competitive DNA. No one wants to admit that they are breakable. We train hard and we eat clean. We do everything we are supposed to do to remain in optimum shape. We are creatures of habit and dedication; we don’t have time for injury. These are all of the thoughts that rattle through our brains because accepting the reality of our new situation is too jarring to comprehend. Eventually, however, reality will set in, which is when we move through to the second stage.

Anger

You leave your doctor’s office infuriated. She’s just told you to completely halt all lifting for the next four weeks. Doesn’t she understand what this means to you? You sit at home, replaying the moments back that lead to that ill-fated fumble. You beat yourself up. You are sure that if you would have done this or that, then the injury wouldn’t have occurred. If you would’ve been more rested, if you would’ve warmed up more, if you would’ve lifted less weight and focused more on form, if you would’ve tried harder. Why didn’t you just try harder? Your emotions start to get the best of you, but you have no outlet for them because you can’t do the one thing you like to do when your emotions are getting the best of you. So how do you manage? You bargain.

Bargaining

In stage three, athletes will start to cut deals with themselves. In our minds, if we promise to do better next time, that fulfills some sort of cosmic healing shortcut that will trim time off of our recovery. You make a solemn oath to your coaches to always heed their advice, as if they have the power to grant your wishes on the spot. You swear a blood oath to yourself that you will work on mobility every day just as soon as your knee heals, then look down at it, waiting for the miracle to happen. But it doesn’t happen. The wishes, and the prayers, and the promises do not accelerate the recovery process, and this catapults you into stage four.

Depression

All hope is lost. You’re going to put on weight. You’re going to lose all of your strength. That hard work you’ve been putting in for the past six months is completely wasted. You might as well have never started training, because by the time you get back to it, you’ll be an out-of-shape slob who has completely forgotten what it’s like to do a bodyweight squat let alone a squat snatch. You can’t bring yourself to even drive by your gym. Seeing people – healthy people – walking through its doors cuts like a knife. “Do they even know how lucky they are,” you mumble under your breath. No. They don’t, and neither did you until it was too late. This is perhaps the hardest stage from which to pull ones self. Depending on the severity of the injury and the longevity of the recovery process, this stage can last weeks or months, perhaps even longer. Once through this dark time, however, you will find yourself in the last stage of the grieving process.

Acceptance

No matter how or when you arrive at this stage, something to keep in mind is that acceptance is not the same thing as feeling fine with your situation. Accepting your injury merely means you have accepted it as your reality. When—and only when—you have made it to stage five can you truly begin the mental healing process. You have finally reached the point where you can think and act on your recovery in a sensible manner, figuring out the next and best courses of action. Perhaps you schedule time to work with a physical therapist if you haven’t already. Maybe talking to a sports psychologist will help you get your head back in the game. Whatever it is that you decide, know that there is a light at the end of the proverbial tunnel. After all, you’ve made it this far.

Knowing, as they say, is half the battle. If you become injured, understanding the grieving process will help you to move through each phase with a little more ease. Be proactive: set up appointments with doctors and physical therapists to help you through this. Lay out a recovery game plan and a timeline you can physically check off. Keep track of your healing progress in a journal, which is also a great outlet for some of that stress and frustration you will undoubtedly feel. In short, tackle your recovery with the same tenacity that you tackle your training.

|

Jennifer Dietrich has a B.A. in English/Creative Writing and an M.A. in Education. She is a high school English teacher, freelance writer/blogger, and USATF certified coach. Jennifer initially came to CrossFit in early 2015 to help build strength and speed. She recently retired from triathlon in order to pursue CrossFit and Olympic weightlifting, as well as to focus on her 5K training. Jennifer resides in Cleveland, Ohio with her husband and two cats. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date