The Importance of Emphasizing Power Training in Older Clients

Muscular power is the ability to quickly generate force, apply it to a load and successfully complete an action. Although we routinely schedule programming that enhances power development in athletes, many times, when training older clients, we concentrate our programming on muscular strength. We often avoid power exercises out of fear of injury or under the assumption that if we increase strength, power will take care of itself. However, as we age, muscle power output decreases at a much faster rate than strength. This means that without appropriately designed training programs that emphasize all aspects of muscular health (endurance, strength, and power), the ability to perform activities of daily living becomes compromised in these individuals and the risk of experiencing a life changing accident or fall increases dramatically.

Overestimating Training Crossover

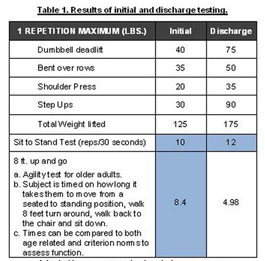

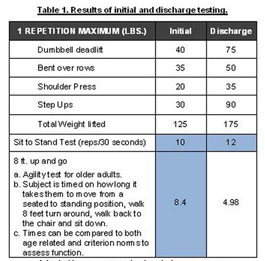

Last September, a student and I investigated the impact of a linear periodized resistance training program on muscular strength and power in individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Before and after training, we measured participant’s 1RM in four lifts (deadlifts, bent over rows, step ups, and shoulder presses) along with scores on the sit to stand and 8 foot up and go mobility scale to determine baseline muscular strength and power. The training program we designed consisted of an endurance phase (60-75% of 1RM with 1-2 sets x 10-12 reps) and a strength phase (85% of 1RM with 2 set of 8 reps). We assumed that training at high loads and low volume would adequately compensate for the lack of a specific power phase. In table one, you can see the initial and discharge results of one of our participants, a 62-year-old male with moderate pulmonary disease.

While we found significant strength gains in all four lifts, he only improved in one of the power measures, the 8-foot up go mobility scale. This really surprised me. Here was a man who increased his 1RM in deadlifts by 30 pounds and his steps-ups by 60 pounds but still scored below average in the chair stand task. Why? A lack of power: the ability to quickly generate force to complete an action. In our programming, we did not specifically address this issue. Also by repeatedly stressing during training the importance of controlling the weight and avoiding ballistic movements, we limited the amount of crossover that might occur. So while there were some changes in muscle power, they weren’t of sufficient intensity to improve scores in both power measures. This is important to note because maintaining health and independence over a lifetime requires individuals possess not only adequate muscle endurance and strength but power as well. Activities that you and I take for granted like stopping a forward fall, climbing steps or stairs, and avoiding oncoming traffic when crossing the street are more about muscle power then strength.

Designing Workouts That Emphasize Power Development

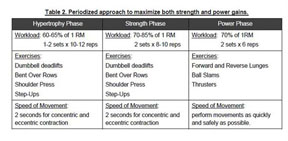

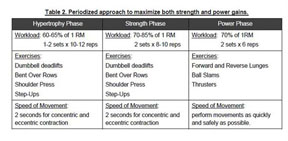

If I could redo the study, I’d shift the focus on the last two weeks to emphasize power development rather than maximize strength gains. Workouts would be built around movements that emphasize speed of force development and rapid changes in direction. As you can see in table 2, I’d replace deadlifts and shoulder press with thrusters, bent over rows with ball slams, and step-ups with lunges.

The load would be 70% of 1 RM with instructions to perform the movements as quickly and safely as possible. Why 70%? Load assignments in the power phase are directly related to the deficits you want to address. The research shows that changes in balance and gait speed are positively impacted with loads of around 40% of 1RM while difficulty in chair stands (my study participant’s limitation/weakness) and stair climbing are more positively impacted with loads of around 70-80% of 1RM. You can use lunges, ball slams and thrusters, as you can see in the table below, but there are a number of other exercises available as well.

By adding a power phase, you directly address the mobility issues we see in older adults and increase the chances of a client maintaining their independence as they age.

Working Around Client Limitations

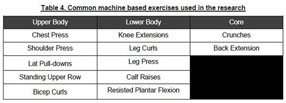

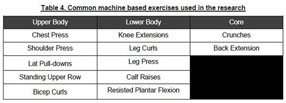

While I’m not a huge fan of isolation work or machines, they can play a role in programming. Machines are a non-threatening, safe, and practical way to introduce adults to lifting. In a review article by Michele Porter in Experimental Gerontology, thirteen of the fifteen studies she described employed machines as their primary training tool (see table 4), with knee extensions being the primary exercise in eleven of the studies.

Keep in mind that many older adults may have range of motion or joint limitations due to poor flexibility or arthritis. Knee extensions performed through a full ROM may cause pain in many individuals, but especially older adults who may have knee osteoarthritis in one or more compartments of the knee. To avoid this Tony Brosky, PT, DHS, Professor of Physical Therapy at Bellarmine University suggests, “if knee extension machines are going to be used, have clients perform them through a limited range of motion from 45-90 degrees while training in the terminal degrees of knee extension (45-0) can be best accomplished through weight bearing activities.” That way, “you facilitate quad strength, limit patellar femoral compression and decrease the chances of exacerbating their arthritis,” says Brosky.

However, as an athlete’s strength and confidence increases, it’s imperative to progress to more complex exercises and movements. Also, only using machines reinforces isolated movements, not patterns of movement and ignores the concept of functional specificity. “Incorporate what you want to achieve into you programming,” says Brosky. Since the activities of daily living consist of movement patterns, not isolated muscle contractions, utilize exercises that mimic those patterns like squats, step-ups, and lunges. Brosky frequently employs partial or quarter lunges in his programs beginning with a simple forward lunge. As clients improve, they graduate to a variety of activities including reverse and diagonal lunges, all positions they could find themselves in if they were to lose their balance.

Putting It All Together

Improving muscle power is a key element in anyone’s training. However, due to the significant losses we see in older adults, exercises emphasizing power play a crucial role in maintaining high levels of mobility and physical function. Utilizing a periodized approach is one way to make sure your clients have these attributes when they need them.

Overestimating Training Crossover

Last September, a student and I investigated the impact of a linear periodized resistance training program on muscular strength and power in individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Before and after training, we measured participant’s 1RM in four lifts (deadlifts, bent over rows, step ups, and shoulder presses) along with scores on the sit to stand and 8 foot up and go mobility scale to determine baseline muscular strength and power. The training program we designed consisted of an endurance phase (60-75% of 1RM with 1-2 sets x 10-12 reps) and a strength phase (85% of 1RM with 2 set of 8 reps). We assumed that training at high loads and low volume would adequately compensate for the lack of a specific power phase. In table one, you can see the initial and discharge results of one of our participants, a 62-year-old male with moderate pulmonary disease.

While we found significant strength gains in all four lifts, he only improved in one of the power measures, the 8-foot up go mobility scale. This really surprised me. Here was a man who increased his 1RM in deadlifts by 30 pounds and his steps-ups by 60 pounds but still scored below average in the chair stand task. Why? A lack of power: the ability to quickly generate force to complete an action. In our programming, we did not specifically address this issue. Also by repeatedly stressing during training the importance of controlling the weight and avoiding ballistic movements, we limited the amount of crossover that might occur. So while there were some changes in muscle power, they weren’t of sufficient intensity to improve scores in both power measures. This is important to note because maintaining health and independence over a lifetime requires individuals possess not only adequate muscle endurance and strength but power as well. Activities that you and I take for granted like stopping a forward fall, climbing steps or stairs, and avoiding oncoming traffic when crossing the street are more about muscle power then strength.

Designing Workouts That Emphasize Power Development

If I could redo the study, I’d shift the focus on the last two weeks to emphasize power development rather than maximize strength gains. Workouts would be built around movements that emphasize speed of force development and rapid changes in direction. As you can see in table 2, I’d replace deadlifts and shoulder press with thrusters, bent over rows with ball slams, and step-ups with lunges.

The load would be 70% of 1 RM with instructions to perform the movements as quickly and safely as possible. Why 70%? Load assignments in the power phase are directly related to the deficits you want to address. The research shows that changes in balance and gait speed are positively impacted with loads of around 40% of 1RM while difficulty in chair stands (my study participant’s limitation/weakness) and stair climbing are more positively impacted with loads of around 70-80% of 1RM. You can use lunges, ball slams and thrusters, as you can see in the table below, but there are a number of other exercises available as well.

By adding a power phase, you directly address the mobility issues we see in older adults and increase the chances of a client maintaining their independence as they age.

Working Around Client Limitations

While I’m not a huge fan of isolation work or machines, they can play a role in programming. Machines are a non-threatening, safe, and practical way to introduce adults to lifting. In a review article by Michele Porter in Experimental Gerontology, thirteen of the fifteen studies she described employed machines as their primary training tool (see table 4), with knee extensions being the primary exercise in eleven of the studies.

Keep in mind that many older adults may have range of motion or joint limitations due to poor flexibility or arthritis. Knee extensions performed through a full ROM may cause pain in many individuals, but especially older adults who may have knee osteoarthritis in one or more compartments of the knee. To avoid this Tony Brosky, PT, DHS, Professor of Physical Therapy at Bellarmine University suggests, “if knee extension machines are going to be used, have clients perform them through a limited range of motion from 45-90 degrees while training in the terminal degrees of knee extension (45-0) can be best accomplished through weight bearing activities.” That way, “you facilitate quad strength, limit patellar femoral compression and decrease the chances of exacerbating their arthritis,” says Brosky.

However, as an athlete’s strength and confidence increases, it’s imperative to progress to more complex exercises and movements. Also, only using machines reinforces isolated movements, not patterns of movement and ignores the concept of functional specificity. “Incorporate what you want to achieve into you programming,” says Brosky. Since the activities of daily living consist of movement patterns, not isolated muscle contractions, utilize exercises that mimic those patterns like squats, step-ups, and lunges. Brosky frequently employs partial or quarter lunges in his programs beginning with a simple forward lunge. As clients improve, they graduate to a variety of activities including reverse and diagonal lunges, all positions they could find themselves in if they were to lose their balance.

Putting It All Together

Improving muscle power is a key element in anyone’s training. However, due to the significant losses we see in older adults, exercises emphasizing power play a crucial role in maintaining high levels of mobility and physical function. Utilizing a periodized approach is one way to make sure your clients have these attributes when they need them.

|

Mark Kaelin, M.S., CSCS is a certified strength and conditioning specialist with the National Strength and Conditioning Association and has almost 20 years of experience working in health and fitness. He is currently an instructor in the biology department at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Ky., and writes frequently for health and fitness publications. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date