Absolute Strength, Absolute Speed, and Everything In Between

When working with high level CrossFit athletes and assessing their relative strengths and weaknesses, I often categorize them as either “faster than strong” or “stronger than fast.” The purpose of this article is not only to shed light of what the aforementioned terms mean, but also to explain their implications and how they affect the development of an athlete.

The Force Velocity Curve:

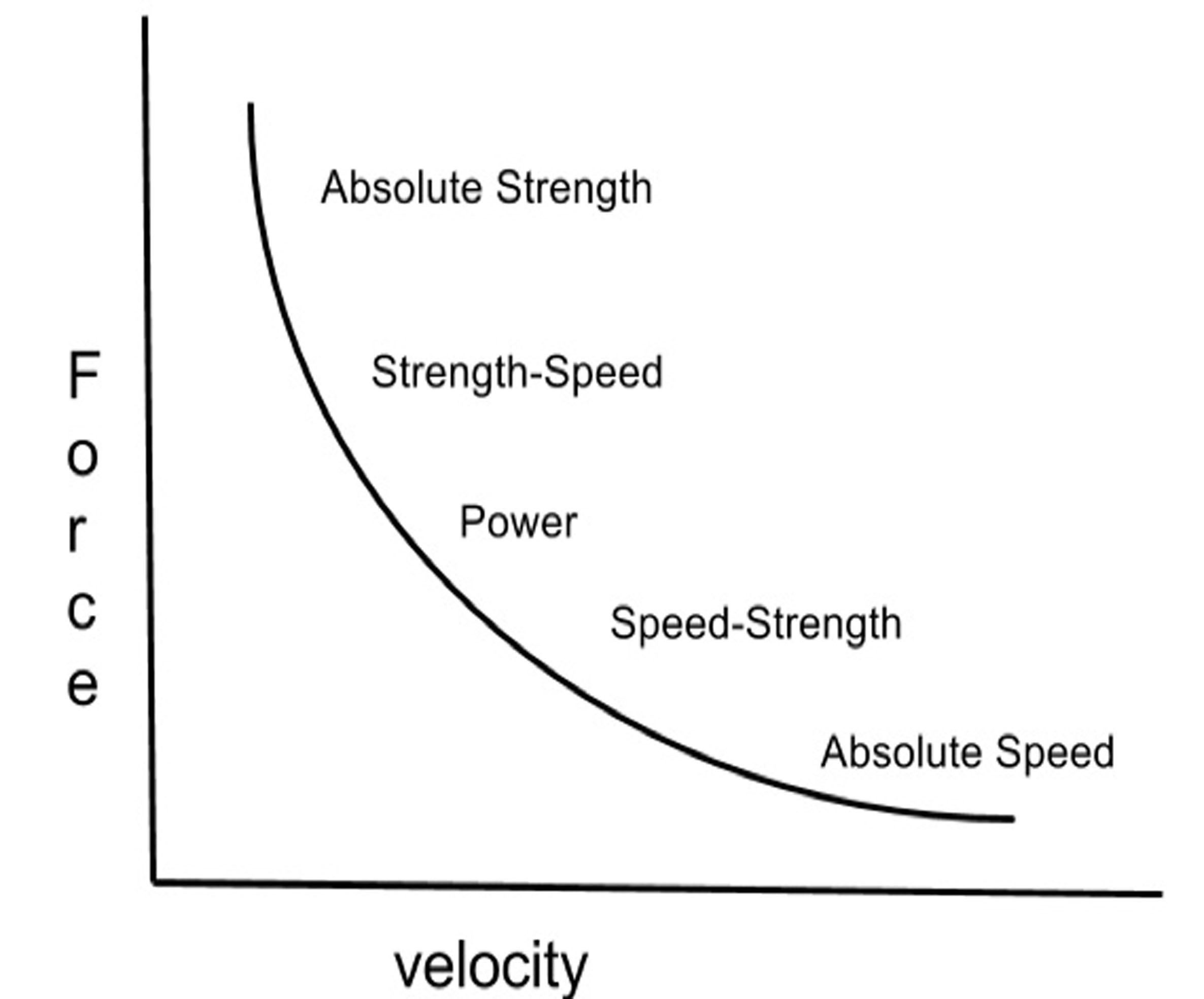

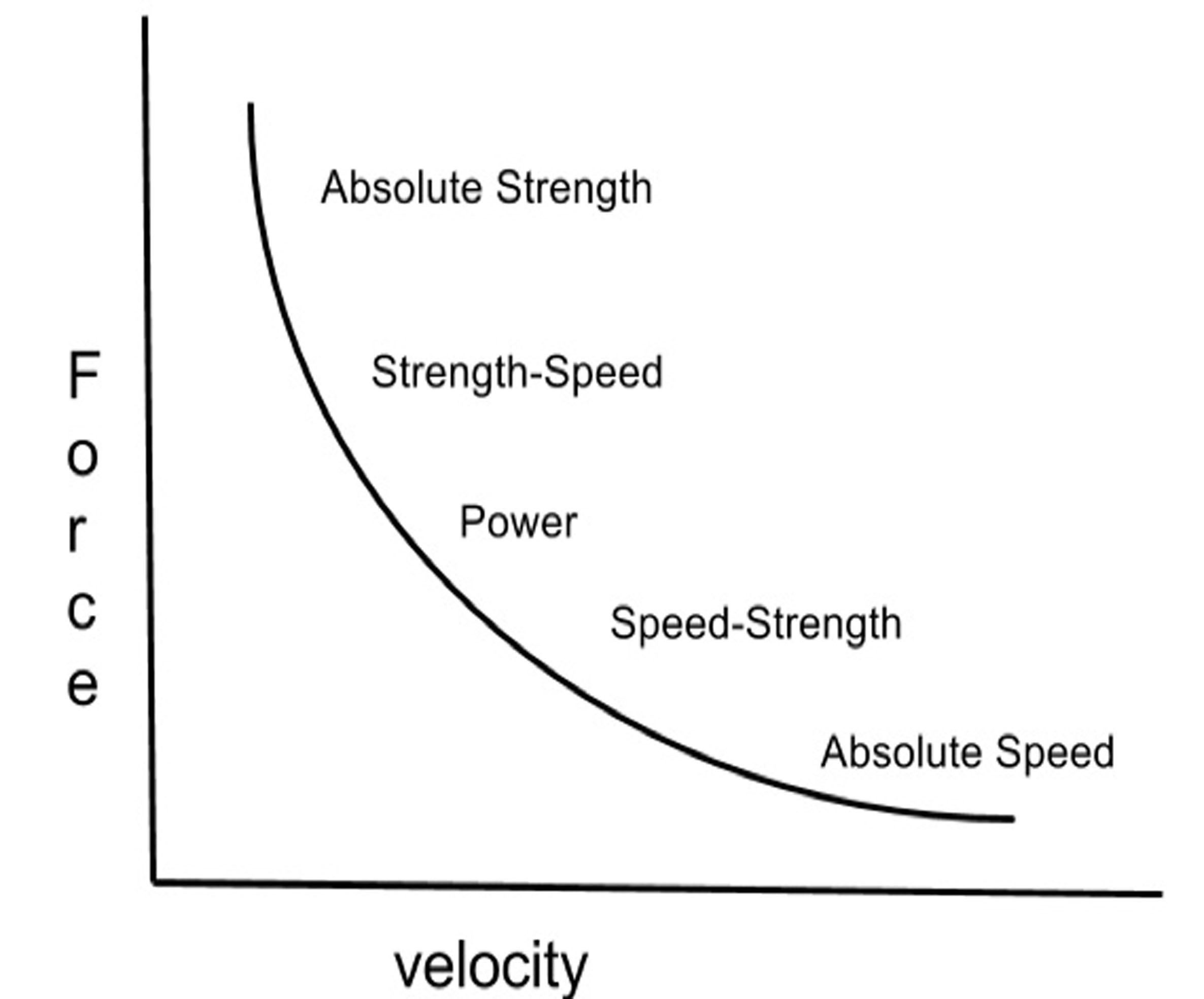

As seen below, the force-velocity curve is a hyperbolic function. (Do you regret not paying attention in 10th grade pre-calc now?) It depicts an inverse relationship between absolute strength and absolute speed--meaning that as force increases, speed decreases, and vice versa.

Why is this relevant to our discussion? Put simply, an athlete will sit somewhere on this curve and in order to maximize their potential in the sport of CrossFit, we want them to sit somewhere in the middle. So, knowing this we can now say that:

1) An athlete who is stronger than fast sits on the left side of the curve—in essence, they need speed development to maximize their power output.

2) An athlete who is faster than strong sits on the right side of the curve, so they need absolute strength development to maximize power output.

3) A balanced athlete will sit on the middle of the curve.

However, this now raises another question: How do we know where an athlete sits on the curve?

When assessing where an athlete lies on the force velocity curve, the specific tests/ assessments we like to use are the relationship between back squat, clean, snatch, and deadlift maxes, as well as video analysis, and a handful of specialized tests. Some specific ratios we look for between lifts are: Clean: Back Squat (75-77%) Snatch: Back Squat (65-67%) Clean: Deadlift (60%) Power Snatch: Full Snatch (87-89%) Power Clean: Full Clean (87-89%) Assuming the athlete in question has full technical proficiency on all lifts, we can conclude the following:

1) An athlete whose numbers fall under the given ratios is stronger than fast--and needs speed development.

2) An athlete whose numbers are over the given ratios is faster than strong—and needs strength development.

For example:

Athlete #1 Cleans 225, Back Squats 275, and Snatches 185lbs. If we run a few of his ratios we get this:

Clean:BS- 81%

Snatch:BS- 69%

Based on this data set, we can determine that this athlete needs absolute strength development to further develop their lifts and become balanced.

The Power Curve

Once we know where an athlete sits on the curve, our goal is now to make them sit towards the middle: in essence, towards power. This will not only make them more balanced in terms of absolute strength/speed, but will increase their potential for improvement in the sport of CrossFit.

Note, however, that different sports have different demands in terms of speed and strength. As such, the goal will not always be to sit in the middle of a curve for all athletes. For example, a strength athlete may benefit from sitting closer to the left side of the curve, while a high jumper or sprinter may benefit from sitting closer to the right side of the curve. This is due to the demands of their sport, and the specific strength characteristics that would allow them to excel (i.e. absolute strength development would be more beneficial to a strength athlete than absolute speed, and the converse can be said for a sprinter or high jumper).

Program Application:

Now that we know how to assess where an athlete sits, as well as where we want them to go, we can discuss how to get them there. But first, some definitions and examples.

Absolute Strength is the maximum amount a person can lift in one repetition--in essence, the maximum force they can exert on an object. Below I’ve included two sample sessions designed to train absolute strength.

Sample Session 1:

A. Back Squat @20x1; 2 reps x10 sets; rest 2m

B1. Push Press; 2-3x5; rest 90s

B2. Romanian Deadlift; 4-6x5; rest 90s

C. Weighted. Pull-up @21x2; 3x3; rest 2m

Sample Session 2:

A. BS Cluster @31x1; [3.3.3]x4; rest 20s/2m

B1. Bench Drop Set; [5.3.2]x3; rest 90s

B2. WCU Cluster; [2.2.2]; rest 20s/90s

C. Singe Leg DL; 4x4/leg; rest 2m

For the sake of keeping these examples simple, I stuck to a straightforward full body training session. The first example is more general, while the second example has specific RX’s used on athletes with low(er) neuromuscular efficiencies since they can handle higher volume relative to their one rep max.

Neuromuscular Efficiency (NME) can be defined as the nervous systems ability to efficiently send impulses from the brain to the muscle fibers. Consequently, enabling muscles to work together properly in all planes of motion.

In order to test NME, we use the “85% test,” which is conducted as follows: An athlete works to a 1RM Back Squat. After they hit their final weight, they rest three to five minutes, and they perform one set of back squats to failure @85% of their daily max. If an athlete gets 1-3 reps, they have a high NME. If they get 4-6 reps, they have a moderate NME, and it they get 7+ reps, they have a low NME.

Strength Speed is a muscular action containing more relative contribution from force than speed. Examples of how to train strength-speed include heavier singles in the Olympic lifts, with adequate rest, where heavy is a relative term depending on a given athlete’s NME. As a general rule, though, the weight will be in the vicinity if 80-90% of their 1RM.

Speed Strength: a muscular action containing more relative contribution from speed than from force. Examples of how to train speed strength are highly sport specific, but in the context of CrossFit, my preferred method for training this quality is EMOM (every minute on the minute) work with the Olympic lifts at light(er) weights relative to the individual (e.g. 55-75% 1RM).

Absolute Speed: The fastest rate at which someone is able to move (the magnitude of velocity). Examples of how to train absolute speed include high turnover repetition work (example: touch and go power cleans), or my preferred method, Anaerobic A-Lactic work. Examples include Aerodyne sprints, or actual sprinting if mechanics allow it.

Be aware that some athletes will not be able to get the dose response on absolute speed work, since they may not be able to generate a high enough power output. Consequently, it is not to be used on beginners or athletes who have far more endurance than power.

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, it’s time to talk specific RX’s...

Note that structural balance, the time of year, and NME are all factors that come into play when determining an Rx to ensure it is appropriate for a given athlete. For example, if an athlete is weak in certain movement patterns, they will not follow the same training prescription as a structurally balanced athlete. Similarly, if an athlete is two weeks out from competition, their training will look a lot different than it would in the off season. That being said, these are general examples and need to be adapted to the individual to be used effectively.

Stronger Than Fast:

As I’ve already touched on, athletes who are stronger than fast will need to spend more time on the right of the force velocity curve, meaning that they should focus on speed strength and absolute speed. A simple example of a workout utilizing both of these--as to avoid confusion regarding which training method is for which characteristic—is this:

A. Power Snatch; 1 rep OTM for 15 Min @60-70% (Speed Strength)

B. 20 Minute EMOM: (Speed Strength)

1 Power Clean & Push Jerk @65-75% (even minutes)

1 Med Ball Reverse Shot Toss (odd minutes)

C. 12 Second Aerodyne @100%; rest __ x__ sets (Absolute Speed)

Faster Than Strong:

If an athlete who is stronger than fast will need to spend more time on the right side of the curve, then it should be obvious that an athlete who is faster than strong should spend more time on the left side of the curve. Here is an example focusing on absolute strength and strength speed.

A. Front Squat @30x1; 2-3x4; rest 2m (Absolute Strength)

B. Clean Pull; build to a heavy triple (drop & reset b/w reps) (Absolute Strength)

C. Hang Clean; 1-1-1-1-1-1-1; rest 2m (start @80%, then build) (Strength-Speed)

The Force Velocity Curve:

As seen below, the force-velocity curve is a hyperbolic function. (Do you regret not paying attention in 10th grade pre-calc now?) It depicts an inverse relationship between absolute strength and absolute speed--meaning that as force increases, speed decreases, and vice versa.

Why is this relevant to our discussion? Put simply, an athlete will sit somewhere on this curve and in order to maximize their potential in the sport of CrossFit, we want them to sit somewhere in the middle. So, knowing this we can now say that:

1) An athlete who is stronger than fast sits on the left side of the curve—in essence, they need speed development to maximize their power output.

2) An athlete who is faster than strong sits on the right side of the curve, so they need absolute strength development to maximize power output.

3) A balanced athlete will sit on the middle of the curve.

However, this now raises another question: How do we know where an athlete sits on the curve?

When assessing where an athlete lies on the force velocity curve, the specific tests/ assessments we like to use are the relationship between back squat, clean, snatch, and deadlift maxes, as well as video analysis, and a handful of specialized tests. Some specific ratios we look for between lifts are: Clean: Back Squat (75-77%) Snatch: Back Squat (65-67%) Clean: Deadlift (60%) Power Snatch: Full Snatch (87-89%) Power Clean: Full Clean (87-89%) Assuming the athlete in question has full technical proficiency on all lifts, we can conclude the following:

1) An athlete whose numbers fall under the given ratios is stronger than fast--and needs speed development.

2) An athlete whose numbers are over the given ratios is faster than strong—and needs strength development.

For example:

Athlete #1 Cleans 225, Back Squats 275, and Snatches 185lbs. If we run a few of his ratios we get this:

Clean:BS- 81%

Snatch:BS- 69%

Based on this data set, we can determine that this athlete needs absolute strength development to further develop their lifts and become balanced.

The Power Curve

Once we know where an athlete sits on the curve, our goal is now to make them sit towards the middle: in essence, towards power. This will not only make them more balanced in terms of absolute strength/speed, but will increase their potential for improvement in the sport of CrossFit.

Note, however, that different sports have different demands in terms of speed and strength. As such, the goal will not always be to sit in the middle of a curve for all athletes. For example, a strength athlete may benefit from sitting closer to the left side of the curve, while a high jumper or sprinter may benefit from sitting closer to the right side of the curve. This is due to the demands of their sport, and the specific strength characteristics that would allow them to excel (i.e. absolute strength development would be more beneficial to a strength athlete than absolute speed, and the converse can be said for a sprinter or high jumper).

Program Application:

Now that we know how to assess where an athlete sits, as well as where we want them to go, we can discuss how to get them there. But first, some definitions and examples.

Absolute Strength is the maximum amount a person can lift in one repetition--in essence, the maximum force they can exert on an object. Below I’ve included two sample sessions designed to train absolute strength.

Sample Session 1:

A. Back Squat @20x1; 2 reps x10 sets; rest 2m

B1. Push Press; 2-3x5; rest 90s

B2. Romanian Deadlift; 4-6x5; rest 90s

C. Weighted. Pull-up @21x2; 3x3; rest 2m

Sample Session 2:

A. BS Cluster @31x1; [3.3.3]x4; rest 20s/2m

B1. Bench Drop Set; [5.3.2]x3; rest 90s

B2. WCU Cluster; [2.2.2]; rest 20s/90s

C. Singe Leg DL; 4x4/leg; rest 2m

For the sake of keeping these examples simple, I stuck to a straightforward full body training session. The first example is more general, while the second example has specific RX’s used on athletes with low(er) neuromuscular efficiencies since they can handle higher volume relative to their one rep max.

Neuromuscular Efficiency (NME) can be defined as the nervous systems ability to efficiently send impulses from the brain to the muscle fibers. Consequently, enabling muscles to work together properly in all planes of motion.

In order to test NME, we use the “85% test,” which is conducted as follows: An athlete works to a 1RM Back Squat. After they hit their final weight, they rest three to five minutes, and they perform one set of back squats to failure @85% of their daily max. If an athlete gets 1-3 reps, they have a high NME. If they get 4-6 reps, they have a moderate NME, and it they get 7+ reps, they have a low NME.

Strength Speed is a muscular action containing more relative contribution from force than speed. Examples of how to train strength-speed include heavier singles in the Olympic lifts, with adequate rest, where heavy is a relative term depending on a given athlete’s NME. As a general rule, though, the weight will be in the vicinity if 80-90% of their 1RM.

Speed Strength: a muscular action containing more relative contribution from speed than from force. Examples of how to train speed strength are highly sport specific, but in the context of CrossFit, my preferred method for training this quality is EMOM (every minute on the minute) work with the Olympic lifts at light(er) weights relative to the individual (e.g. 55-75% 1RM).

Absolute Speed: The fastest rate at which someone is able to move (the magnitude of velocity). Examples of how to train absolute speed include high turnover repetition work (example: touch and go power cleans), or my preferred method, Anaerobic A-Lactic work. Examples include Aerodyne sprints, or actual sprinting if mechanics allow it.

Be aware that some athletes will not be able to get the dose response on absolute speed work, since they may not be able to generate a high enough power output. Consequently, it is not to be used on beginners or athletes who have far more endurance than power.

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, it’s time to talk specific RX’s...

Note that structural balance, the time of year, and NME are all factors that come into play when determining an Rx to ensure it is appropriate for a given athlete. For example, if an athlete is weak in certain movement patterns, they will not follow the same training prescription as a structurally balanced athlete. Similarly, if an athlete is two weeks out from competition, their training will look a lot different than it would in the off season. That being said, these are general examples and need to be adapted to the individual to be used effectively.

Stronger Than Fast:

As I’ve already touched on, athletes who are stronger than fast will need to spend more time on the right of the force velocity curve, meaning that they should focus on speed strength and absolute speed. A simple example of a workout utilizing both of these--as to avoid confusion regarding which training method is for which characteristic—is this:

A. Power Snatch; 1 rep OTM for 15 Min @60-70% (Speed Strength)

B. 20 Minute EMOM: (Speed Strength)

1 Power Clean & Push Jerk @65-75% (even minutes)

1 Med Ball Reverse Shot Toss (odd minutes)

C. 12 Second Aerodyne @100%; rest __ x__ sets (Absolute Speed)

Faster Than Strong:

If an athlete who is stronger than fast will need to spend more time on the right side of the curve, then it should be obvious that an athlete who is faster than strong should spend more time on the left side of the curve. Here is an example focusing on absolute strength and strength speed.

A. Front Squat @30x1; 2-3x4; rest 2m (Absolute Strength)

B. Clean Pull; build to a heavy triple (drop & reset b/w reps) (Absolute Strength)

C. Hang Clean; 1-1-1-1-1-1-1; rest 2m (start @80%, then build) (Strength-Speed)

|

Evan Peikon, Co-Owner of High Performance Athlete, originally became interested in health & performance after competing in Track & Field and becoming a student of the sport. After receiving a career-ending injury, he became set on finding a smarter, sustainable, way to train. He is now a full-time athlete, student, and coach whose passions lie in biochemistry, nutrition, health/longevity, and optimal human performance. For more information, you can find Evan Peikon at http://www.HP-Athlete.com |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date