Tapering for Competition

Athletes train to compete. More importantly, they train to win. Why else would they put in hours of training in a day just to come in second? Whether an athlete’s season is three competitions or 20 competitions long, they should be at their peak performance levels for those few competitions that are the most important to have the best chance to come away with a victory. One way coaches can help ensure athletes are physically ready is a taper period.

A taper is a period of time in an athlete’s periodized program when intensity, volume, and frequency are altered to elicit performance gains. Just as intensity, volume, and frequency can be altered to impose a training stimulus, these three variables can be controlled to encourage desired increases in performance. During a taper period and as you get closer to competition; the goal should be to keep adaptation rates high while minimizing fatigue.

The average improvement for a trained athlete given an appropriate taper is two to three percent, or zero to six percent, depending on the sport. Top athletes will most likely be at higher proportions to their “performance ceiling”, so percentage improvements will generally be slightly less (half a percent to three percent). It is comparable to an overweight person with a goal of losing weight. The initial weight loss will come pretty easily with a moderate amount of work. As the person loses weight, it is much harder (and unrealistic) for that person to continue to lose the same amount of weight from month to month; just as it’s hard for an elite athlete to see large gains when they get closer and closer to his or her “performance ceiling.”

Tapering should start two to three weeks out from competition. Here are a few central fundamentals that should be taken into consideration when developing the competition taper:

• Volume

• Intensity

• Frequency

• Training Age

• Type of Athlete

Volume

Volume in this sense is the amount of work done (sets, reps, distance, time, etc.). Inigo Mujika, an expert on recovery and performance, suggests a 40 to 60 percent volume reduction over the course of two to three weeks. It is important to note that there should be an accumulation of volume over the course of a training plan, so there is something to reduce from when appropriate. The consequence of not accumulating volume can lead to a potential decrease in performance when tapering the suggested 40-60 percent. If you decrease too much from an already relatively low volume of work, you will short-change yourself on training stimulus.

Intensity

Intensity refers to the percentage you are working at relative to your rep max. Over the course of a training cycle, intensity should be gradually increasing until the taper period. At that point, intensity should remain relatively stable over the course of the taper. Maintaining intensity while dropping volume can assist in the ultimate goal: reducing fatigue while maintaining and improving strength and power.

Frequency

Frequency represents how many training sessions you or your athlete is performing in a given time frame. In a competition-tapering phase, frequency, like intensity, should remain unchanged if tolerated by the athlete (a maximum of 20 percent reduction in frequency if needed). For ease of example, imagine seven-day microcycles. Some elite athletes perform as many as 10+ training sessions in a given week, whereas other athletes may only train three sessions a week. There may be good reason to drop a couple of sessions from an athlete’s program when they are training 10+ sessions a week, but if you’re only training three sessions a week, there is no real logical reason to drop a training session from an already low training frequency.

Training Age

Training age can also be considered a component in this tapering equation. Training age refers to the accumulation of training time over the athlete’s career. This doesn’t mean that athletes with low training ages are necessarily young athletes. An athlete in their mid-twenties who has trained for a few months has a lower training age than a 16-year-old who has been training for three years, despite being chronologically younger. If an athlete has only trained for a few months, they are more than likely at a lower level relative to their genetic potential. When you or your athlete’s performance levels are lower, you shouldn’t need as much time to rebound from training because training is not placing as great of demand on your body.

Think of two identical Ferraris: One is consistently operating at 90 percent of its speed potential, while the other is operating at 50 percent of its speed potential. The Ferrari that is operating at 90 percent (the elite athlete) is stressing the components under the hood much more than the Ferrari that is operating at 50 percent. The Ferrari working consistently at 90 percent will need more maintenance checks and occasional recovery periods to make sure everything stays working properly. The same applies to elite athletes in comparison to novice or amateur athletes.

Knowing Yourself and Your Athlete

Certain types of athletes respond differently to these three training components (volume, intensity, and frequency). For the general athlete, these guidelines are best practice. However, there are always outliers to any guideline or rule-of-thumb. Over time, coaches can start understanding when to tweak certain components in a tapering period and what adjustments should be made.

When is an athlete in the most favorable position to be at their peak performance? Remember, this is where the real coaching comes in to play. Start the taper too late, and the athlete could potentially under-perform because they are still in a fatigued state. Start the taper too early, and you have an athlete that peaks early and is potentially on the downswing of the adaptation curve and subsequently under-performs.

Coaches and athletes alike can also start understanding what combination of volume, intensity, frequency brings out the best performances. Developing this coach-athlete relationship is beneficial to ultimately discover what combination works best.

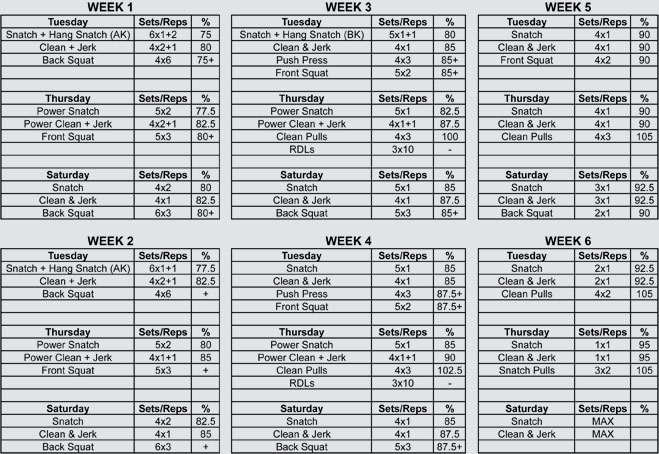

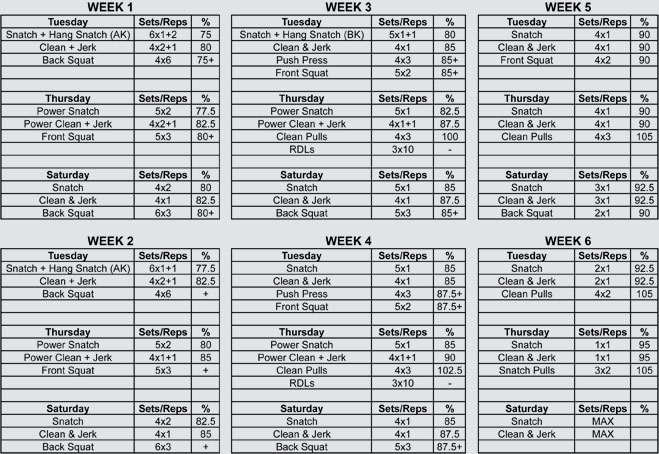

This is a 6-week program for an athlete training three days per week. The program is geared to improve the full competition lifts with a max day at the end of six weeks.

The program starts at a relatively low intensities and moderate volumes. Over the course of the six weeks, volumes and intensities are trending upward. At the start of Week 5 (the start of tapering), volume is reduced while intensities are increasing minimally.

There are no changes in training frequency during the taper since this is only a three day per week program.

It should be noted that the sets and reps listed are working sets and there should be build-up sets proceeding.

References:

David B. Pyne; Intildeigo Mujika; Thomas Reilly. Peaking for optimal performance: Research limitations and future directions. Journal of Sports Sciences. (2009). 27.3. pp 195-202

Hausswirth, C., Mujika, I. (2013). Recovery for Performance in Sport. Champagne, IL: Human Kinetics

A taper is a period of time in an athlete’s periodized program when intensity, volume, and frequency are altered to elicit performance gains. Just as intensity, volume, and frequency can be altered to impose a training stimulus, these three variables can be controlled to encourage desired increases in performance. During a taper period and as you get closer to competition; the goal should be to keep adaptation rates high while minimizing fatigue.

The average improvement for a trained athlete given an appropriate taper is two to three percent, or zero to six percent, depending on the sport. Top athletes will most likely be at higher proportions to their “performance ceiling”, so percentage improvements will generally be slightly less (half a percent to three percent). It is comparable to an overweight person with a goal of losing weight. The initial weight loss will come pretty easily with a moderate amount of work. As the person loses weight, it is much harder (and unrealistic) for that person to continue to lose the same amount of weight from month to month; just as it’s hard for an elite athlete to see large gains when they get closer and closer to his or her “performance ceiling.”

Tapering should start two to three weeks out from competition. Here are a few central fundamentals that should be taken into consideration when developing the competition taper:

• Volume

• Intensity

• Frequency

• Training Age

• Type of Athlete

Volume

Volume in this sense is the amount of work done (sets, reps, distance, time, etc.). Inigo Mujika, an expert on recovery and performance, suggests a 40 to 60 percent volume reduction over the course of two to three weeks. It is important to note that there should be an accumulation of volume over the course of a training plan, so there is something to reduce from when appropriate. The consequence of not accumulating volume can lead to a potential decrease in performance when tapering the suggested 40-60 percent. If you decrease too much from an already relatively low volume of work, you will short-change yourself on training stimulus.

Intensity

Intensity refers to the percentage you are working at relative to your rep max. Over the course of a training cycle, intensity should be gradually increasing until the taper period. At that point, intensity should remain relatively stable over the course of the taper. Maintaining intensity while dropping volume can assist in the ultimate goal: reducing fatigue while maintaining and improving strength and power.

Frequency

Frequency represents how many training sessions you or your athlete is performing in a given time frame. In a competition-tapering phase, frequency, like intensity, should remain unchanged if tolerated by the athlete (a maximum of 20 percent reduction in frequency if needed). For ease of example, imagine seven-day microcycles. Some elite athletes perform as many as 10+ training sessions in a given week, whereas other athletes may only train three sessions a week. There may be good reason to drop a couple of sessions from an athlete’s program when they are training 10+ sessions a week, but if you’re only training three sessions a week, there is no real logical reason to drop a training session from an already low training frequency.

Training Age

Training age can also be considered a component in this tapering equation. Training age refers to the accumulation of training time over the athlete’s career. This doesn’t mean that athletes with low training ages are necessarily young athletes. An athlete in their mid-twenties who has trained for a few months has a lower training age than a 16-year-old who has been training for three years, despite being chronologically younger. If an athlete has only trained for a few months, they are more than likely at a lower level relative to their genetic potential. When you or your athlete’s performance levels are lower, you shouldn’t need as much time to rebound from training because training is not placing as great of demand on your body.

Think of two identical Ferraris: One is consistently operating at 90 percent of its speed potential, while the other is operating at 50 percent of its speed potential. The Ferrari that is operating at 90 percent (the elite athlete) is stressing the components under the hood much more than the Ferrari that is operating at 50 percent. The Ferrari working consistently at 90 percent will need more maintenance checks and occasional recovery periods to make sure everything stays working properly. The same applies to elite athletes in comparison to novice or amateur athletes.

Knowing Yourself and Your Athlete

Certain types of athletes respond differently to these three training components (volume, intensity, and frequency). For the general athlete, these guidelines are best practice. However, there are always outliers to any guideline or rule-of-thumb. Over time, coaches can start understanding when to tweak certain components in a tapering period and what adjustments should be made.

When is an athlete in the most favorable position to be at their peak performance? Remember, this is where the real coaching comes in to play. Start the taper too late, and the athlete could potentially under-perform because they are still in a fatigued state. Start the taper too early, and you have an athlete that peaks early and is potentially on the downswing of the adaptation curve and subsequently under-performs.

Coaches and athletes alike can also start understanding what combination of volume, intensity, frequency brings out the best performances. Developing this coach-athlete relationship is beneficial to ultimately discover what combination works best.

This is a 6-week program for an athlete training three days per week. The program is geared to improve the full competition lifts with a max day at the end of six weeks.

The program starts at a relatively low intensities and moderate volumes. Over the course of the six weeks, volumes and intensities are trending upward. At the start of Week 5 (the start of tapering), volume is reduced while intensities are increasing minimally.

There are no changes in training frequency during the taper since this is only a three day per week program.

It should be noted that the sets and reps listed are working sets and there should be build-up sets proceeding.

References:

David B. Pyne; Intildeigo Mujika; Thomas Reilly. Peaking for optimal performance: Research limitations and future directions. Journal of Sports Sciences. (2009). 27.3. pp 195-202

Hausswirth, C., Mujika, I. (2013). Recovery for Performance in Sport. Champagne, IL: Human Kinetics

|

John Grace is a Sport Performance Coach at Athletic Lab where he coaches youth to elite level athletes in a wide range of sports. He is currently earning his Master's degree from Ohio University in Coaching & Sport Science. John is a Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist, USA Track & Field and USA Weightlifting Level 1 Coach. In addition, he served as the Assistant Fitness Coach of the 2013 MLS Vancouver Whitecaps alongside Dr. Mike Young. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date