The Olympic Lift Starting Position

The starting position (and first pull by relation) is a topic that has attracted a considerable degree of confusion, skepticism and attitude within the CrossFit and broader strength and conditioning communities (not within the weightlifting community—there’s little disagreement on what works and what doesn’t). I’m going to do my best to clear up this little misunderstanding and save people the trouble of having to unlearn bad habits.

Keep in mind during this adventure that what I present here is in no way some original creation of mine. I’ve not attempted to reinvent a perfectly functional wheel or prove the weightlifting world wrong with my superior intellect—I’m simply teaching and describing what has been demonstrated most effective by coaches and athletes around the world for years.

The Basic Idea

Before we continue, let’s first establish what exactly we’re talking about.

Most importantly, we need to understand this: The sole purpose of the starting position (and first pull) is to allow an optimal second pull.

If you take away only one point from this entire article, it should be that one. If you don’t understand that, none of the following details explaining or describing the starting position will matter.

The second pull of the snatch and clean is the source of the overwhelming majority of the upward acceleration of the barbell—it is the heart of the lift. The first pull serves only to optimize the second; the starting position serves to allow that second-pull-optimizing first pull.

The optimal second pull position is defined in essence by the ideal degree of concurrent knee and hip flexion and balance on the feet to generate maximal force against the ground and therefore upward acceleration of the barbell.

Basically our goal in the starting position is to maintain the most upright back angle possible. This should not be misunderstood to mean that we’d prefer a vertical torso over any degree of forward lean. We do need an angle on the torso to allow hip extension to contribute, along with knee extension, to the upward acceleration of the bar. However, we can conveniently say as upright as possible, because we know there’s a very definite limit to how upright we can actually place the torso. That upper limit is the angle of the back produced by placing the bar over the base of the toes and bringing the arms to a vertical orientation.

There are a few basic reasons for this that to individuals who actually spend time snatching and cleaning heavy weights are quite obvious and not subjected to much challenge.

First, this more upright angle minimizes hip and lumbar torque and consequently fatigue of the spinal erectors during the first pull. Because the lower back is most easily fatigued relative to the other muscle groups involved in the lift, and these muscles must be able to maintain rigidity of the spine during the second pull in order to maximize the conversion of hip and knee extension power to acceleration of the barbell, more work by the lower back early in the lift will mean less rigidity and more of the hips’ and legs’ power being absorbed by back flexion.

Second, the reduced torque on the hips with a more upright back angle allows greater hip extension speed during the second pull because the lower degree of initial torque allows better acceleration and creates less fatigue. Consider attempting a maximal vertical jump—if given the choice, would you start from a full squat (full knee and hip flexion), or a depth closer to a quarter squat (partial hip and knee flexion)? At what angle of a stiff-legged deadlift or good morning can you really accelerate the bar? Try it if you’re confused.

Third, the shorter rotational distance during the second pull minimizes the demands on balance maintenance and allows the athlete to focus more on the power of execution rather than the balance of the system.

Fourth, such an upright posture encourages the bar to remain close to the body where it needs to be without so much additional effort due to the angle of the arms being nearer to their natural loaded orientation.

Finally, athletes will generally feel more comfortable in a more upright position and consequently be better prepared psychologically for a successful lift. This reason cannot be underestimated in terms of its contribution to lift success. Convincing yourself to pull under a very heavy barbell is unquestionably an exercise in mental fortitude.

Assume the Position

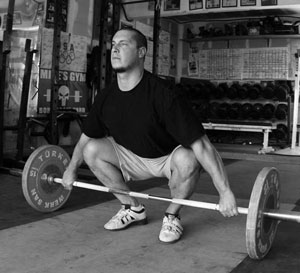

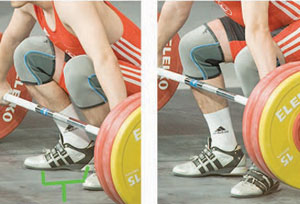

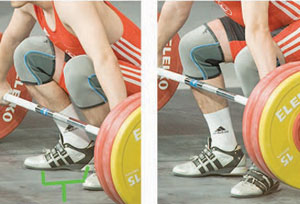

The starting position I teach—again, that I teach, not that I invented—is defined by two basic points. The barbell begins approximately over the base of the toes, and the arms are vertical when viewed from the side. Simple enough.

It may be helpful to rename the base of the toes the balls of the feet since the inclusion of the word “toes” seems to confuse some people and result in the bar being placed over the toes, rather than over their attachment to the foot as desired.

Is there something magical about this bar position? In a way—It’s the farthest forward we can start the bar and still be capable of lifting it from the floor. Why do we need it so far forward? Because we need to create space for us to get into position with vertical arms—as the hips drop, the knees bend, and the shins move forward. Unless the bar moves forward, the shins can’t, and consequently we can’t bend the knees and drop the hips.

Occasionally you’ll run across someone who happens to be proportioned just right and can assume the start position with the bar farther back over the foot. In these cases, this is the preferred approach. But attempting this without the proper proportions just results in either the bar having to be swung forward around the knees, or having to lift the hips ahead of the shoulders in order to get the knees out of the way. Neither is something we want, although a slight swing around the knees is far preferable because it allows the upright back angle we’re after—both Stefan Botev and Ivan Chakarov managed to lift remarkably heavy weights in this fashion.

In regard to the shoulders, yes, they will be slightly (SLIGHTLY) in front of the bar in this position. Look at an arm-shoulder unit. You’ll notice, excepting gross physical deformation, that the muscles of the shoulder protrude farther forward than those of the upper arm when in this position. That means that with a vertical arm orientation, that shoulder mass will protrude farther forward than the arm. Since the arm is attached to the barbell approximately at its centerline by the hand, this means the shoulder is and must be slightly ahead of the bar. Moving on.

So where are the hips? I don’t know; I haven’t measured you. If you’re on the short end of the scale, the hips will most likely be above the knees; if you’re a bit longer-legged, the hips may be even with or even slightly below the knees. Understand that hip height is a product of our two basic position criteria (bar over the base of the toes and arms vertical from side), not a criterion itself.

We need to also flare the knees out to the sides, likely until they’re in light contact with the insides of the arms. This positioning effectively shortens the length of the legs and allows us to bring the hips closer to the knees and bar, thereby allowing an even more upright posture and reducing the distance the knees protrude over the bar, making its path clearer.

Ideally we will maintain this same initial back angle throughout the first pull—that is, all the way until the bar reaches about mid-thigh and we fire off that second pull hip and knee extension. However, with taller lifters, we will often need to allow that back angle to shift very slightly in the first couple inches of the first pull. In other words, after the bar is separated from the platform, the hips will rise ahead of the shoulders for just a brief moment to set a new back angle that is then maintained for the remainder of the first pull. This will also begin happening with all lifters as loading becomes extremely heavy because of the mechanical disadvantage of the knee joint in this position.

Thankfully this shift will happen quite naturally. That said, this needs to be controlled to prevent it from being exaggerated and putting us right back into that high-hipped position we’re trying to avoid. Again, the shift will be very subtle and occur by the time the bar has moved the first few inches off the floor. All the athlete needs to do is continue attempting to lift with the back angle unchanged.

So if we’re going to allow this shift, what’s the point of starting with the hips lower? Two reasons. First, it takes effort to separate the bar from the floor. If we can undertake this effort, even if it’s only part of the total effort, from a better position, we’re still at an advantage. Remember our point earlier about minimizing lower back fatigue. Second, it acts as a hedge against excessive hip-leading—that is, if we can begin at a lower point, we’re still in a good position with a little hip-leading; if we attempt to start in that adjusted position, it’s likely we’ll still experience a slight shift. So by remaining in that ideal start position, we’re minimizing departure from it.

Choose Your Own Adventure

If you’re easily distracted, skip the rest of this article and stick to the previous information. If you’re sure you’ll remember the most important information above and want to geek out on some more details, come along.

Balance

But wait! If the bar is over the base of the toes, we’ll be out of balance and fall on our faces!

The fact is, we can all balance on the balls of our feet quite well, and we can prove this to ourselves by standing up right now and trying it. Remarkable.

More importantly, just because we start in a certain position with the center of mass balanced over a particular region of the foot doesn’t mean it must remain there for the rest of the lift. Surprisingly enough, we can actually control this. We are the masters of our destiny.

Now—with the bar beginning over the base of the toes, if that bar is significantly heavy in relation to our bodies, at the moment it separates from the platform, our center of mass will be over the balls of the feet or close to it. Prior to this, in the starting position we set in order to begin the lift, this vertical arm / bar over the base of the toes position will place the great majority of our body’s mass well behind the bar, keeping us quite well and easily balanced, unlike in a high-hipped starting position, in which a considerable chunk of the torso is over the bar, and the remainder of the body closer to it.

Because we ultimately don’t want our weight over the balls of the feet, we do need to correct this quickly. The correction is remarkably simple—shift back slightly as you separate the bar from the floor rather than attempting to lift it straight up.

This backward shift to move our weight back over the foot is what creates the slight backward curve of the bar path when viewed from the side.

The Myth of the Vertical Bar Path

A curve in the bar path? That’s not efficient!

Well, no, it’s not efficient if we consider a barbell in isolation being moved by some undefined force. Why would we want to move a bar any more than we needed to? We wouldn’t. But that’s missing the point. And what’s the point again? The point is that the sole purpose of the starting position and first pull are to allow an optimal second pull.

Moreover, efficiency is a fairly irrelevant concept in this situation for a few seemingly obvious reasons, foremost of which is the fact that we’re not talking about a simple machine performing a repetitive movement, but a more complicated system attempting to accelerate a specific object a single time. If you’re looking to build the fastest, most powerful car possible (let’s say no concern for street legality), do you make fuel efficiency a criterion?

And if we decide we do want to consider efficiency, we’re still better off from a very practical standpoint with a more upright posture. We can think of efficiency as an ability to maximize the quantity of work done in a given period of time. We can worry about the distance the bar must travel, factoring in its horizontal movement as well, and be concerned about those few small inches that require no actual effort over a proportionately enormous vertical distance that requires great effort; or we can instead concern ourselves with reducing the limiting effects of the weakest element in the system—the lower back.

As was explained previously, the more upright pulling posture that forces this slight horizontal bar path deviation also reduces fatigue of the lower back by shifting more of the effort to larger, more fatigue-resistant muscle groups. This immediately increases the number of reps possible in a particular period of time by pushing the point of the weakest link’s failure farther down the timeline.

Arguments regarding efficiency notwithstanding, there is a very important point to understand: You’re not a forklift. You’re comprised of far more complex articulations, and the simple reality is that what’s most efficient (in terms of distance of travel) for a magically floating barbell in space is not necessarily what’s most effective for a barbell being lifted by a human being on Earth. Mechanically, we’re stronger, quicker and more effective at accelerating and moving that barbell from our desired starting and ending points in certain positions than we are in others. The goal, then, must be to ensure we place ourselves in those more effective positions, even if that means a slight deviation from a tidy little vertical bar path.

And we need to be honest with ourselves about the degree of the deviation and its effects on the lift. First, we’re talking about movement of a few inches at most within a total vertical distance of 5-6 feet for an average size dude. This alone should reassure you that such a deviation is not exactly calamitous.

Further, we need to understand how this bar is making that horizontal movement. It’s in the air and consequently encounters no resistance from friction (at least not a consequential amount). Were it a difficult movement demanding of genuine effort, we might be more inclined to avoid it. But fortunately, we can achieve this slight backward path with no real effort beyond what’s already required to pick up the bar from the ground.

Attaching the Bar to the Body

This leads us nicely to the topic of how and where the bar is attached to us. We hold the bar in the hands; the hands are attached to the ends of the arms; the other ends of the arms are attached to the top of the torso.

Like a plumb line, the arm always wants to simply hang vertically from its origin under load. We can demonstrate this by holding a light bar or dumbbells, leaning over and relaxing. The load will immediately move and settle with the arms vertical. We can adjust the angle of the back and repeat. The arms settle into a vertical orientation.

What complicates things is the fact that as we lean forward, the attachments of the arms to the torso (called “shoulders”), move farther forward of our base (called “feet”). With our empty bar or girly dumbbells, this isn’t a problem—we can lean quite far forward and still allow the arms to hang vertically without falling over simply by pushing our hips back slightly.

However, as we increase the weight we’re holding, problems arise. This forward shifting of the shoulders, even with a backward shift of the hips, means that in order to remain balanced over our base, the bar must be pulled back into our bodies, reorienting the arms from their desired vertical orientation to an angle in order to re-center the bar-body complex’s mass over the feet.

Additionally, the body wants to minimize the work it has to do, and the easiest way to do that is to shorten the length of the resistance lever arms—this is accomplished by bringing the weight closer to the body, which decreases the torque on the hip and back.

This movement is quite a natural response to the created imbalance in this situation. That is, if you stuck an untrained person with no instruction in this position, he or she would lean back and pull the bar into his or her body instead of falling on his or her face.

We can get around this problem in our little demonstration by simply supporting the torso with some sturdy object like an elevated bench or plyo box. With this configuration, we remove the need to maintain our balance over a fixed and concentrated base. We can now load up that bar or grab big kids’ dumbbells and allow ourselves to relax—and watch the arms orient themselves naturally to a vertical position.

Irrespective of the angle of the back, the arms naturally want to hang vertically

This should also be pretty obvious to anyone who’s ever lifted a heavy barbell. If the arms didn’t want to remain vertical, why would we have to continue exerting effort to pull the bar back into our bodies when our shoulders were in front of the bar? If their natural orientation under load was an angle of some degree, that would be the orientation they assumed in the absence of controlling efforts. This is obviously and demonstrably not the case.

if we support the torso, we can avoid the problems of balancing on the feet and torque on the

hips and back, and use more weight. Whether dumbbells, an empty bar, a loaded bar, the arms

continue to hang vertically. We can place the torso at any angle, and this vertical orientation remains.

So—if we begin our lift with the arms vertical, they don’t want to go anywhere else once the bar is no longer supported by the ground. The natural reaction is for the arms to continue searching for that vertical position no matter what kinds of shenanigans we get into with the torso.

This means that when we initiate the lift and shift our weight from over the balls of the feet to over the front edge of the heels, keeping the angle of the back the same or nearly so, the shoulders remain in approximately the same position relative to the hips. This being the case, the bar has no reason to do anything but come right along with the rest of the body. In other words, we don’t need to apply any additional effort to reposition the barbell during this backward shift—it wants to come back to us. Even if we get a slight forward movement of the shoulders relative to the hips, the arms will still be very close to their original vertical orientation, and as a consequent the effort to hold the bar back closer to the body will remain minimal.

If instead we position ourselves in the start with the bar farther back over the foot and the shoulders farther forward of the bar—that is, in a position that would allow a neat little vertical bar path—we now have a loaded pendulum waiting to be released.

In such a position, the instant the bar separates from the platform and is supported only by the body, it wants to swing forward. Only through conscious effort (quite a bit with real weight) can we keep the bar close to our bodies; likewise, only through great effort can we prevent our weight from shifting immediately forward onto our toes.

Because this is very difficult to control, and rarely is controlled, it results in the lifter chasing after the bar, which means a premature and awkward scoop that precludes the additional power of the natural double knee bend—this is an effort to get under the bar before the bar-body unit falls over. Completed lifts will involve a jump forward to receive the bar, which makes that receipt far more difficult and more stressful on the joints; and when the weight actually becomes significant, this phenomenon simply results in snatches missed in front and cleans dropped from the rack—if they’ve even made it to that point.

We also tend to get a change in the body extension pattern. Rather than knee extension followed by hip extension followed by knee extension (the pattern produced by the double knee bend that creates so much upward momentum on the bar), we get concurrent or nearly so hip and knee extension.

Basically what we end up with is more reminiscent of a kettlebell swing than a vertical jump, the latter being the movement we’re trying to mimic in order to accelerate the bar upward. Consider the feeling of a kettlebell swing—where does the force of the movement go? Have you ever jumped off the floor inadvertently when swinging? No, you haven’t, because there’s no vertical drive from the legs—the hips simply slam forward into extension along with the knees.

What happens when the hips and knees extend in this fashion during a snatch or clean? Simple—the bar is driven forward by the thighs and/or hips rather than being pulled up by the ascending shoulders and brushing up the thighs and hips on its way. In other words, its motion is oriented in the wrong direction. This not only contributes to the tendency for the bar to pull us forward—which is already greater than it should be—but it dramatically reduces upward acceleration by removing those final inches of vertical leg drive.

This is a remarkably important point that deserves bold type: The double knee bend is a natural movement that happens to increase the power of the second pull (remember, our first priority) through a stretch-shortening cycle in the quads. If we enter the second pull in a sound position—that is, with the correct degree of knee and hip flexion and balance over the feet—the contraction of the hamstrings to extend the hip will force the knees to bend again slightly and shift forward (the scoop). This movement of the knees stretches the quad, and the continued effort by the lifter to drive against the floor with the legs immediately extends them again, that extension potentiated by the stretch of the quads. With a high-hipped starting position and first pull, we invariably preclude this phenomenon—we limit significantly the amount of power we can generate to accelerate the bar.

In addition, like Glenn Pendlay so astutely pointed out to me the other day (after explaining to me that this article was far too long and convoluted, which is true, but irresolvable at this point), from this high-hipped, shoulders-forward starting position, the bulk of the body’s mass has to move forward in order to keep the bar traveling in a vertical line—this further shifts the weight forward and makes preventing that shift to the toes and forward bar swing even more difficult.

In short, by setting ourselves up for a vertical bar path for the sake of optimizing “efficiency”—a wholly impertinent concept—we’ve set ourselves up for a host of serious problems, as well as preventing maximal bar acceleration. This, to state it simply, is a bad idea.

Back to the Arm Angle

What allows the backward movement of the bar from this vertical-arm starting position is the fact that as we extend our knees in the first pull, the shins move back. This clears a path for the bar that was blocked initially by the position of the shins in the start, which were either in light contact with the bar or in very close proximity. Basically, if we move the body as a whole correctly, the bar follows suit quite obediently.

However, we run into some complications farther up the pull. As the knees continue extending, they move farther back, as do the shins. Basically the depth of the bar-body unit shrinks as we extend upward. In order to remain balanced, we have to move back weight from front of center in equal amount to the weight in back of center that’s moving forward. This is done with a natural constant shift of the body back slightly as we extend, and by keeping the bar as close to the legs as possible. If our initial back angle remains the same, this will require pulling the bar back toward the body by angling the arms somewhat. This shift is quite minimal if we’re in the desired posture already, and consequently the effort to pull the bar into the body is similarly minimal.

Recall earlier in the discussion of the arm’s desired dangle angle that the body will naturally pull the bar into the body in order to remain balanced over the feet. We can rely on this to a large extent if we begin in the correct position and don’t stray from it—if we increase the forward lean of the torso, we place ourselves beyond the realm of expecting reasonably for this to happen, and find ourselves instead in a position in which we not only have to exert great effort to keep the bar close, but may actually exceed our ability to do so in terms of strength. This means the bar pulls us forward and we have to chase it. You’ve all seen this phenomenon, and likely experienced it personally—athletes jumping forward into a bar that’s escaping, and then throwing temper tantrums following the miss.

But in the Deadlift…

But in the deadlift, this happens… When I deadlift, I do this… When my clients deadlift, I see this…

Let’s start simple and warm up for the more complex concepts. The snatch and the clean are not the deadlift. I promise this insight will prove quite valuable when considering the respective starting positions of these lifts.

I understand the comparison—I really do. The bar starts on the floor, you hang onto it, and you stand up. There are a lot of similarities. However, it turns out there are even more differences, and rather critical ones.

In an effort to prevent extending this particular article to unnecessarily epic lengths, I’m going to simply point out the fact that after that standing up part, there are still a bunch of other things that need to happen in the snatch and clean. In the deadlift, you just put the weight back down.

Remember—the starting position and first pull of the snatch and clean serve one purpose: to optimize the second pull of the lift, the part during which the athlete is actually generating the overwhelming majority of the acceleration of the bar. In other words, it’s first and foremost a positioning movement for another, more important movement. You’ll notice this point has now been repeated a number of times—pay attention.

The deadlift, on the other hand, is nothing more than a slow and boring first pull—about as simple and straightforward as an exercise can possibly get. Get yourself balanced, hold on tight, and stand up. It’s entirely self-contained, and what happens before and after doesn’t matter.

In addition to this little pearl, we need to keep in mind that whatever weights an athlete—no matter how powerful and technically proficient—is snatching and cleaning, he or she is capable of deadlifting significantly more, even if that athlete rarely or never trains the deadlift directly. This being the case, it should be obvious that what may be deemed unavoidable in a maximal effort deadlift will not necessarily be such in a snatch or clean, maximal or otherwise.

Shoulders, Hips and Feet, Oh My!

In a heavy deadlift, the body will naturally position itself and relate itself to the bar in whatever manner is necessary to move that bar. For example, we can roll the bar six inches forward of our toes and initiate the lift from there, but I can assure you that before the bar separates from the platform, it will have first rolled back over the feet to at least the most forward point at which we can apply upward force without falling over (about the balls of the feet, as it happens), or we will have stepped forward to place the feet under the bar.

Similarly, we can sit in behind the bar with our shoulders behind it, and consequently the arms behind vertical, and tug on the bar all we want. However, it won’t go anywhere other than into our shins until the body readjusts itself into a position in which the arms’ attachments to the torso have aligned themselves above the bar.

These adjustments are wholly natural because they’re necessary to initiate the bar’s separation from the ground. We don’t need to intentionally place ourselves in any special position to execute this separation—all we need to do is not allow ourselves to fall over while pulling on the bar.

The important point of all this is simple: a maximal deadlift is literally a full-body maximal effort, and as such, we have little to no control over the position our bodies assume when executing it—it will always place itself in whatever position it finds most likely to allow completion of the lift, and the degree to which that position strays from our intended one will be commensurate to the amount of weight we’re trying to move.

This is an important distinction between the deadlift and the snatch and clean. Because, as we’ve said previously, snatch and clean weights will always be considerably lower than deadlift weights, we’re still within the realm of postural control from which the maximal deadlift departs. That is, even with a maximal effort clean, an athlete will still be able to a large degree to control the position from which he or she pulls the bar from the floor—this includes things like relative hip and shoulder height and the extension of the back.

If we tell ourselves that the first pull of the snatch and clean are identical to that of the deadlift (or should be), we would quite naturally be compelled to follow the rules of the deadlift. Those rules, as we now understand, are simple: whatever works to move the weight. Never in the history of maximal effort deadlifts has there been an extended spine—a rounded back is the hallmark of a truly heavy deadlift, and to at least some degree, is unavoidable under such weights. So should we perform all of our deadlifts—and our snatches and cleans—with a rounded back intentionally?

Similarly, in a maximal effort deadlift, no matter the starting position of the hips, they will assuredly rise faster than the shoulders and wind up in a higher position, unless started at a height at which the knees are nearing full extension. This phenomenon is quite simple: in a low-hipped position, the angle of the knee is such that its mechanics are quite disadvantaged—that is, it’s very difficult to extend the knee under the full load. Because the body knows what to do, it will naturally begin extending the knees with minimal bar movement until the angle of the knee is such that it can bear the full load and begin moving the barbell along with the rest of the body. This is a very obvious adjustment to relieve the legs (meaning the quads) of some of the work and shift more of it to the back and hips—in the weightlifting world commonly referred to as unloading the legs. It has nothing to do with the arms, shoulders, 12-sided dice, or anything else—it has to do exclusively with the fact that in such an instance, the quads are not strong enough to move the weight. The solution? Strengthen the correct positions and movement.

Try it Again. This Time with Feeling.

We can talk about this all we want, and no matter how articulate, charming and witty I may be, the best way to convince you that this starting position is the most effective is for you to experience that effectiveness yourself.

So my humble suggestion is this—try it. A radical idea, I know. But it turns out you haven’t earned an argument if you haven’t genuinely evaluated this method.

This is a simple experiment, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. If this is not your current starting position, you’re going to have to actually learn to do it properly—including developing the requisite strength—before the evaluation process can begin. Don’t come tell me it didn’t work for you if you can’t even do it correctly.

A high-hipped, shoulders-a-mile-over-the-bar, bar-over-mid-foot starting position is remarkably easy to learn and immediately put into practice—this is, in my opinion, the primary reason it’s become more popular among those unexposed to the weightlifting community. The fact of the matter is, the first pull is actually quite difficult technically—it’s no easy task to navigate the knees while maintaining correct posture, balance and bar position—and quite difficult in terms of strength. Beginning with the hips higher and the knees more extended eliminates the bulk of these complications by eliminating the bulk of the knee extension from the movement and creating a movement dominated by hip extension. This can quickly get novice lifters performing more successfully by avoiding a part of the lift that creates problems for them, and often problems that manifest in later parts of the lift. In other words, it appears upon a glance to improve lifting technique.

But I can’t do it!

That’s because you have little girly quads and need to do more grown-up squats and pulls. This more upright pulling posture demands much greater quad strength than the high-hipped start, and consequently, if your quads are not strong enough, you won’t be able to maintain such a posture as the load increases. This doesn’t mean you’re beyond hope—it just means you need to adjust your training accordingly and shore up the weak spots instead of giving up, crying about it, and sticking your ass back up in the air.

Let’s Get Serious. For Reals.

Now that we know what a good starting position and first pull should look like, the question is, does it always happen like that with technically proficient lifters? Not exactly.

The fact is, advanced lifters are fighting the same forces with the same anatomy novice lifters are, and at maximal weights they’re subject to experiencing the same problems, just to lesser degrees because of their greater experience and strength specificity. For example, the heavier their weights get, the more their bodies will want to unload their legs and shift the hips up—the difference is that those shifts are much smaller, and they’re lifting way more weight than you are.

And having said that, there is a fairly broad range of abilities even at more advanced levels of weightlifting. I can quickly point out a number of top American lifters, for example, who have trouble maintaining such pulling postures, but who remain successful on the national level because, despite this problem, they’re still excellent athletes, and typically very strong. That said, none of our lifters currently rank with the leaders of the international weightlifting community. Granted this is due overwhelmingly to the differences in drug testing (and consequently use), but this simply means there’s a strength and power disparity, and our international counterparts with that greater strength are able to execute excellent technique farther up the loading scale because that technique requires technique-specific strength to execute.

This is not a confusing concept. We can ask a weak little kid to deadlift 50 kg and watch his back round unavoidably under the load. Does this prove to us that no one can lift more than 50 kg while maintaining spinal extension? Of course not; it demonstrates that this kid needs to get stronger. If we get that kid’s best deadlift to 100 kg, we’ll find that 50 kg goes up with perfect pulling posture.

One can go poke around the internet and find videos showing relatively advanced weightlifters (i.e. some of the Americans I alluded to earlier) executing lifts with significant hip-leading and make claims about this position being ultimately unavoidable, so it’s only logical to simply start there for the sake of efficiency. Since we already know how efficiency factors into this, let’s move on.

It’s important to keep in mind that in reality, there’s really no way to prove a claim—only to disprove one. All it takes is a single example that defies that claim to prove that it’s untrue. One need only look at some more videos to see—quite quickly—that such claims regarding the unavoidability of this high-hipped position are wholly unfounded.

The former videos are simply examples of somewhat less developed technique and correspondingly less developed position-specific strength. The less strength an athlete has specific to the movement in question, the sooner on the loading scale he or she will depart from the desired positions. There is no magic point on that scale beyond which maintaining this posture is impossible—the argument should instead be for improving the athlete’s strength in the necessary positions instead of abandoning a more technically difficult movement demanding of greater technique-specific strength in favor of a simplified version that ultimately limits one’s potential performance.

Further, the idea that this upright pulling posture is so common simply because it’s tradition is an argument overwhelmingly void of merit. Tradition is not by its nature flawed, and in fact, can be the result of certain practices being established over time as the most effective. If the weightlifting community as a whole has over the years of technique evolution gravitated to a specific set of pulling rules with little variation, it’s not an accident—it’s a product of coaches and athletes actively involved in the sport continually searching for the best possible methods of snatching and clean & jerking, and continuing to refine those methods through experimentation with their athletes. And of course, it seems somewhat silly to state that things are done in such a way simply because “they’ve always been done that way” when there have been dramatic changes in snatch and clean & jerk technique over the years—the claim is entirely baseless.

Finally, the idea that the best coaches and athletes involved in a sport are disinclined to use whatever works best, despite convention, is utter nonsense, and to suggest otherwise is not only terribly presumptuous, but arrogant, pretentious, insulting to every legitimate coach and athlete in the community, and indicative of a remarkable failure to understand the sport in general and its lift technique specifically.

I’m not even going to make you do your own internet poking for photos and videos—we can disprove the notion that departing from an upright pulling posture, at any point in the lift, is unavoidable with a couple photos:

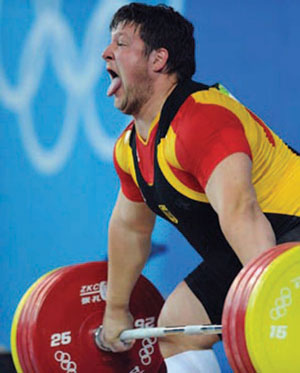

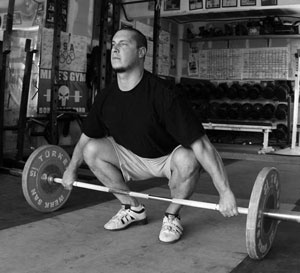

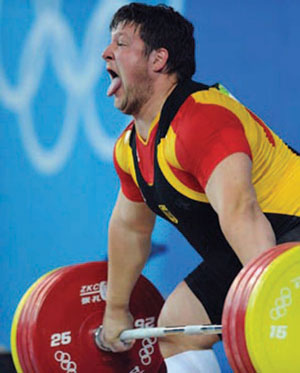

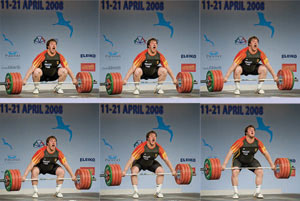

That’s 2008 superheavyweight Olympic gold-medalist Matthias Steiner of Germany. In that photo, he’s snatching over 200 kg (440 lbs). Notice the angle of his back and the orientation of his arms—and that’s with the bar all the way up at knee-height, the point by which it’s been claimed one will unavoidably shift to the back angle associated with the high-hipped, shoulders-forward start. Since this lift is among the heaviest snatches ever performed, it seems fairly clear that it is not, in fact, impossible to maintain such a posture, even at the heaviest loading.

Matthias Steiner demonstrating excellent pulling technique. Notice how little

his back angle shifts during the lift, despite an extremely upright initial posture.

Throughour the pull, his arms deviate from a vertical orientation only minimally.

The following photo is of Taner Sagir initiating a snatch of at least 160 kg—and at a bodyweight of only 77 kg. To be clear, we’re looking at a more than double bodyweight snatch—that is, an extremely heavy weight in the lift that requires the lowest starting position in terms of the hips and shoulders. And look at that—with the bar a couple inches off the floor, Sagir has managed to maintain his upright posture with the arms oriented approximately vertically.

Just for fun—and to make sure we cover all the bases for the most intransigent skeptics—let’s watch a video of Steiner’s gold-medal winning 258 kg (569 lbs) clean & jerk. Pay close attention to the angle of his back and the orientation of his arms.

If you still believe a barbell can’t be snatched or cleaned with an upright posture, you’re beyond any help I’m able to offer.

Let’s Stop

That’s enough. If I haven’t convinced you by now to at the very least legitimately evaluate this starting position yourself, I have no hope of doing so. Give it a shot and enjoy the new records.

Keep in mind during this adventure that what I present here is in no way some original creation of mine. I’ve not attempted to reinvent a perfectly functional wheel or prove the weightlifting world wrong with my superior intellect—I’m simply teaching and describing what has been demonstrated most effective by coaches and athletes around the world for years.

The Basic Idea

Before we continue, let’s first establish what exactly we’re talking about.

Most importantly, we need to understand this: The sole purpose of the starting position (and first pull) is to allow an optimal second pull.

If you take away only one point from this entire article, it should be that one. If you don’t understand that, none of the following details explaining or describing the starting position will matter.

The second pull of the snatch and clean is the source of the overwhelming majority of the upward acceleration of the barbell—it is the heart of the lift. The first pull serves only to optimize the second; the starting position serves to allow that second-pull-optimizing first pull.

The optimal second pull position is defined in essence by the ideal degree of concurrent knee and hip flexion and balance on the feet to generate maximal force against the ground and therefore upward acceleration of the barbell.

Basically our goal in the starting position is to maintain the most upright back angle possible. This should not be misunderstood to mean that we’d prefer a vertical torso over any degree of forward lean. We do need an angle on the torso to allow hip extension to contribute, along with knee extension, to the upward acceleration of the bar. However, we can conveniently say as upright as possible, because we know there’s a very definite limit to how upright we can actually place the torso. That upper limit is the angle of the back produced by placing the bar over the base of the toes and bringing the arms to a vertical orientation.

There are a few basic reasons for this that to individuals who actually spend time snatching and cleaning heavy weights are quite obvious and not subjected to much challenge.

First, this more upright angle minimizes hip and lumbar torque and consequently fatigue of the spinal erectors during the first pull. Because the lower back is most easily fatigued relative to the other muscle groups involved in the lift, and these muscles must be able to maintain rigidity of the spine during the second pull in order to maximize the conversion of hip and knee extension power to acceleration of the barbell, more work by the lower back early in the lift will mean less rigidity and more of the hips’ and legs’ power being absorbed by back flexion.

Second, the reduced torque on the hips with a more upright back angle allows greater hip extension speed during the second pull because the lower degree of initial torque allows better acceleration and creates less fatigue. Consider attempting a maximal vertical jump—if given the choice, would you start from a full squat (full knee and hip flexion), or a depth closer to a quarter squat (partial hip and knee flexion)? At what angle of a stiff-legged deadlift or good morning can you really accelerate the bar? Try it if you’re confused.

Third, the shorter rotational distance during the second pull minimizes the demands on balance maintenance and allows the athlete to focus more on the power of execution rather than the balance of the system.

Fourth, such an upright posture encourages the bar to remain close to the body where it needs to be without so much additional effort due to the angle of the arms being nearer to their natural loaded orientation.

Finally, athletes will generally feel more comfortable in a more upright position and consequently be better prepared psychologically for a successful lift. This reason cannot be underestimated in terms of its contribution to lift success. Convincing yourself to pull under a very heavy barbell is unquestionably an exercise in mental fortitude.

Assume the Position

The starting position I teach—again, that I teach, not that I invented—is defined by two basic points. The barbell begins approximately over the base of the toes, and the arms are vertical when viewed from the side. Simple enough.

It may be helpful to rename the base of the toes the balls of the feet since the inclusion of the word “toes” seems to confuse some people and result in the bar being placed over the toes, rather than over their attachment to the foot as desired.

Is there something magical about this bar position? In a way—It’s the farthest forward we can start the bar and still be capable of lifting it from the floor. Why do we need it so far forward? Because we need to create space for us to get into position with vertical arms—as the hips drop, the knees bend, and the shins move forward. Unless the bar moves forward, the shins can’t, and consequently we can’t bend the knees and drop the hips.

Occasionally you’ll run across someone who happens to be proportioned just right and can assume the start position with the bar farther back over the foot. In these cases, this is the preferred approach. But attempting this without the proper proportions just results in either the bar having to be swung forward around the knees, or having to lift the hips ahead of the shoulders in order to get the knees out of the way. Neither is something we want, although a slight swing around the knees is far preferable because it allows the upright back angle we’re after—both Stefan Botev and Ivan Chakarov managed to lift remarkably heavy weights in this fashion.

In regard to the shoulders, yes, they will be slightly (SLIGHTLY) in front of the bar in this position. Look at an arm-shoulder unit. You’ll notice, excepting gross physical deformation, that the muscles of the shoulder protrude farther forward than those of the upper arm when in this position. That means that with a vertical arm orientation, that shoulder mass will protrude farther forward than the arm. Since the arm is attached to the barbell approximately at its centerline by the hand, this means the shoulder is and must be slightly ahead of the bar. Moving on.

So where are the hips? I don’t know; I haven’t measured you. If you’re on the short end of the scale, the hips will most likely be above the knees; if you’re a bit longer-legged, the hips may be even with or even slightly below the knees. Understand that hip height is a product of our two basic position criteria (bar over the base of the toes and arms vertical from side), not a criterion itself.

We need to also flare the knees out to the sides, likely until they’re in light contact with the insides of the arms. This positioning effectively shortens the length of the legs and allows us to bring the hips closer to the knees and bar, thereby allowing an even more upright posture and reducing the distance the knees protrude over the bar, making its path clearer.

Ideally we will maintain this same initial back angle throughout the first pull—that is, all the way until the bar reaches about mid-thigh and we fire off that second pull hip and knee extension. However, with taller lifters, we will often need to allow that back angle to shift very slightly in the first couple inches of the first pull. In other words, after the bar is separated from the platform, the hips will rise ahead of the shoulders for just a brief moment to set a new back angle that is then maintained for the remainder of the first pull. This will also begin happening with all lifters as loading becomes extremely heavy because of the mechanical disadvantage of the knee joint in this position.

Thankfully this shift will happen quite naturally. That said, this needs to be controlled to prevent it from being exaggerated and putting us right back into that high-hipped position we’re trying to avoid. Again, the shift will be very subtle and occur by the time the bar has moved the first few inches off the floor. All the athlete needs to do is continue attempting to lift with the back angle unchanged.

So if we’re going to allow this shift, what’s the point of starting with the hips lower? Two reasons. First, it takes effort to separate the bar from the floor. If we can undertake this effort, even if it’s only part of the total effort, from a better position, we’re still at an advantage. Remember our point earlier about minimizing lower back fatigue. Second, it acts as a hedge against excessive hip-leading—that is, if we can begin at a lower point, we’re still in a good position with a little hip-leading; if we attempt to start in that adjusted position, it’s likely we’ll still experience a slight shift. So by remaining in that ideal start position, we’re minimizing departure from it.

Choose Your Own Adventure

If you’re easily distracted, skip the rest of this article and stick to the previous information. If you’re sure you’ll remember the most important information above and want to geek out on some more details, come along.

Balance

But wait! If the bar is over the base of the toes, we’ll be out of balance and fall on our faces!

The fact is, we can all balance on the balls of our feet quite well, and we can prove this to ourselves by standing up right now and trying it. Remarkable.

More importantly, just because we start in a certain position with the center of mass balanced over a particular region of the foot doesn’t mean it must remain there for the rest of the lift. Surprisingly enough, we can actually control this. We are the masters of our destiny.

Now—with the bar beginning over the base of the toes, if that bar is significantly heavy in relation to our bodies, at the moment it separates from the platform, our center of mass will be over the balls of the feet or close to it. Prior to this, in the starting position we set in order to begin the lift, this vertical arm / bar over the base of the toes position will place the great majority of our body’s mass well behind the bar, keeping us quite well and easily balanced, unlike in a high-hipped starting position, in which a considerable chunk of the torso is over the bar, and the remainder of the body closer to it.

Because we ultimately don’t want our weight over the balls of the feet, we do need to correct this quickly. The correction is remarkably simple—shift back slightly as you separate the bar from the floor rather than attempting to lift it straight up.

This backward shift to move our weight back over the foot is what creates the slight backward curve of the bar path when viewed from the side.

The Myth of the Vertical Bar Path

A curve in the bar path? That’s not efficient!

Well, no, it’s not efficient if we consider a barbell in isolation being moved by some undefined force. Why would we want to move a bar any more than we needed to? We wouldn’t. But that’s missing the point. And what’s the point again? The point is that the sole purpose of the starting position and first pull are to allow an optimal second pull.

Moreover, efficiency is a fairly irrelevant concept in this situation for a few seemingly obvious reasons, foremost of which is the fact that we’re not talking about a simple machine performing a repetitive movement, but a more complicated system attempting to accelerate a specific object a single time. If you’re looking to build the fastest, most powerful car possible (let’s say no concern for street legality), do you make fuel efficiency a criterion?

And if we decide we do want to consider efficiency, we’re still better off from a very practical standpoint with a more upright posture. We can think of efficiency as an ability to maximize the quantity of work done in a given period of time. We can worry about the distance the bar must travel, factoring in its horizontal movement as well, and be concerned about those few small inches that require no actual effort over a proportionately enormous vertical distance that requires great effort; or we can instead concern ourselves with reducing the limiting effects of the weakest element in the system—the lower back.

As was explained previously, the more upright pulling posture that forces this slight horizontal bar path deviation also reduces fatigue of the lower back by shifting more of the effort to larger, more fatigue-resistant muscle groups. This immediately increases the number of reps possible in a particular period of time by pushing the point of the weakest link’s failure farther down the timeline.

Arguments regarding efficiency notwithstanding, there is a very important point to understand: You’re not a forklift. You’re comprised of far more complex articulations, and the simple reality is that what’s most efficient (in terms of distance of travel) for a magically floating barbell in space is not necessarily what’s most effective for a barbell being lifted by a human being on Earth. Mechanically, we’re stronger, quicker and more effective at accelerating and moving that barbell from our desired starting and ending points in certain positions than we are in others. The goal, then, must be to ensure we place ourselves in those more effective positions, even if that means a slight deviation from a tidy little vertical bar path.

And we need to be honest with ourselves about the degree of the deviation and its effects on the lift. First, we’re talking about movement of a few inches at most within a total vertical distance of 5-6 feet for an average size dude. This alone should reassure you that such a deviation is not exactly calamitous.

Further, we need to understand how this bar is making that horizontal movement. It’s in the air and consequently encounters no resistance from friction (at least not a consequential amount). Were it a difficult movement demanding of genuine effort, we might be more inclined to avoid it. But fortunately, we can achieve this slight backward path with no real effort beyond what’s already required to pick up the bar from the ground.

Attaching the Bar to the Body

This leads us nicely to the topic of how and where the bar is attached to us. We hold the bar in the hands; the hands are attached to the ends of the arms; the other ends of the arms are attached to the top of the torso.

Like a plumb line, the arm always wants to simply hang vertically from its origin under load. We can demonstrate this by holding a light bar or dumbbells, leaning over and relaxing. The load will immediately move and settle with the arms vertical. We can adjust the angle of the back and repeat. The arms settle into a vertical orientation.

What complicates things is the fact that as we lean forward, the attachments of the arms to the torso (called “shoulders”), move farther forward of our base (called “feet”). With our empty bar or girly dumbbells, this isn’t a problem—we can lean quite far forward and still allow the arms to hang vertically without falling over simply by pushing our hips back slightly.

However, as we increase the weight we’re holding, problems arise. This forward shifting of the shoulders, even with a backward shift of the hips, means that in order to remain balanced over our base, the bar must be pulled back into our bodies, reorienting the arms from their desired vertical orientation to an angle in order to re-center the bar-body complex’s mass over the feet.

Additionally, the body wants to minimize the work it has to do, and the easiest way to do that is to shorten the length of the resistance lever arms—this is accomplished by bringing the weight closer to the body, which decreases the torque on the hip and back.

This movement is quite a natural response to the created imbalance in this situation. That is, if you stuck an untrained person with no instruction in this position, he or she would lean back and pull the bar into his or her body instead of falling on his or her face.

We can get around this problem in our little demonstration by simply supporting the torso with some sturdy object like an elevated bench or plyo box. With this configuration, we remove the need to maintain our balance over a fixed and concentrated base. We can now load up that bar or grab big kids’ dumbbells and allow ourselves to relax—and watch the arms orient themselves naturally to a vertical position.

Irrespective of the angle of the back, the arms naturally want to hang vertically

This should also be pretty obvious to anyone who’s ever lifted a heavy barbell. If the arms didn’t want to remain vertical, why would we have to continue exerting effort to pull the bar back into our bodies when our shoulders were in front of the bar? If their natural orientation under load was an angle of some degree, that would be the orientation they assumed in the absence of controlling efforts. This is obviously and demonstrably not the case.

if we support the torso, we can avoid the problems of balancing on the feet and torque on the

hips and back, and use more weight. Whether dumbbells, an empty bar, a loaded bar, the arms

continue to hang vertically. We can place the torso at any angle, and this vertical orientation remains.

So—if we begin our lift with the arms vertical, they don’t want to go anywhere else once the bar is no longer supported by the ground. The natural reaction is for the arms to continue searching for that vertical position no matter what kinds of shenanigans we get into with the torso.

This means that when we initiate the lift and shift our weight from over the balls of the feet to over the front edge of the heels, keeping the angle of the back the same or nearly so, the shoulders remain in approximately the same position relative to the hips. This being the case, the bar has no reason to do anything but come right along with the rest of the body. In other words, we don’t need to apply any additional effort to reposition the barbell during this backward shift—it wants to come back to us. Even if we get a slight forward movement of the shoulders relative to the hips, the arms will still be very close to their original vertical orientation, and as a consequent the effort to hold the bar back closer to the body will remain minimal.

If instead we position ourselves in the start with the bar farther back over the foot and the shoulders farther forward of the bar—that is, in a position that would allow a neat little vertical bar path—we now have a loaded pendulum waiting to be released.

In such a position, the instant the bar separates from the platform and is supported only by the body, it wants to swing forward. Only through conscious effort (quite a bit with real weight) can we keep the bar close to our bodies; likewise, only through great effort can we prevent our weight from shifting immediately forward onto our toes.

Because this is very difficult to control, and rarely is controlled, it results in the lifter chasing after the bar, which means a premature and awkward scoop that precludes the additional power of the natural double knee bend—this is an effort to get under the bar before the bar-body unit falls over. Completed lifts will involve a jump forward to receive the bar, which makes that receipt far more difficult and more stressful on the joints; and when the weight actually becomes significant, this phenomenon simply results in snatches missed in front and cleans dropped from the rack—if they’ve even made it to that point.

We also tend to get a change in the body extension pattern. Rather than knee extension followed by hip extension followed by knee extension (the pattern produced by the double knee bend that creates so much upward momentum on the bar), we get concurrent or nearly so hip and knee extension.

Basically what we end up with is more reminiscent of a kettlebell swing than a vertical jump, the latter being the movement we’re trying to mimic in order to accelerate the bar upward. Consider the feeling of a kettlebell swing—where does the force of the movement go? Have you ever jumped off the floor inadvertently when swinging? No, you haven’t, because there’s no vertical drive from the legs—the hips simply slam forward into extension along with the knees.

What happens when the hips and knees extend in this fashion during a snatch or clean? Simple—the bar is driven forward by the thighs and/or hips rather than being pulled up by the ascending shoulders and brushing up the thighs and hips on its way. In other words, its motion is oriented in the wrong direction. This not only contributes to the tendency for the bar to pull us forward—which is already greater than it should be—but it dramatically reduces upward acceleration by removing those final inches of vertical leg drive.

This is a remarkably important point that deserves bold type: The double knee bend is a natural movement that happens to increase the power of the second pull (remember, our first priority) through a stretch-shortening cycle in the quads. If we enter the second pull in a sound position—that is, with the correct degree of knee and hip flexion and balance over the feet—the contraction of the hamstrings to extend the hip will force the knees to bend again slightly and shift forward (the scoop). This movement of the knees stretches the quad, and the continued effort by the lifter to drive against the floor with the legs immediately extends them again, that extension potentiated by the stretch of the quads. With a high-hipped starting position and first pull, we invariably preclude this phenomenon—we limit significantly the amount of power we can generate to accelerate the bar.

In addition, like Glenn Pendlay so astutely pointed out to me the other day (after explaining to me that this article was far too long and convoluted, which is true, but irresolvable at this point), from this high-hipped, shoulders-forward starting position, the bulk of the body’s mass has to move forward in order to keep the bar traveling in a vertical line—this further shifts the weight forward and makes preventing that shift to the toes and forward bar swing even more difficult.

In short, by setting ourselves up for a vertical bar path for the sake of optimizing “efficiency”—a wholly impertinent concept—we’ve set ourselves up for a host of serious problems, as well as preventing maximal bar acceleration. This, to state it simply, is a bad idea.

Back to the Arm Angle

What allows the backward movement of the bar from this vertical-arm starting position is the fact that as we extend our knees in the first pull, the shins move back. This clears a path for the bar that was blocked initially by the position of the shins in the start, which were either in light contact with the bar or in very close proximity. Basically, if we move the body as a whole correctly, the bar follows suit quite obediently.

However, we run into some complications farther up the pull. As the knees continue extending, they move farther back, as do the shins. Basically the depth of the bar-body unit shrinks as we extend upward. In order to remain balanced, we have to move back weight from front of center in equal amount to the weight in back of center that’s moving forward. This is done with a natural constant shift of the body back slightly as we extend, and by keeping the bar as close to the legs as possible. If our initial back angle remains the same, this will require pulling the bar back toward the body by angling the arms somewhat. This shift is quite minimal if we’re in the desired posture already, and consequently the effort to pull the bar into the body is similarly minimal.

Recall earlier in the discussion of the arm’s desired dangle angle that the body will naturally pull the bar into the body in order to remain balanced over the feet. We can rely on this to a large extent if we begin in the correct position and don’t stray from it—if we increase the forward lean of the torso, we place ourselves beyond the realm of expecting reasonably for this to happen, and find ourselves instead in a position in which we not only have to exert great effort to keep the bar close, but may actually exceed our ability to do so in terms of strength. This means the bar pulls us forward and we have to chase it. You’ve all seen this phenomenon, and likely experienced it personally—athletes jumping forward into a bar that’s escaping, and then throwing temper tantrums following the miss.

But in the Deadlift…

But in the deadlift, this happens… When I deadlift, I do this… When my clients deadlift, I see this…

Let’s start simple and warm up for the more complex concepts. The snatch and the clean are not the deadlift. I promise this insight will prove quite valuable when considering the respective starting positions of these lifts.

I understand the comparison—I really do. The bar starts on the floor, you hang onto it, and you stand up. There are a lot of similarities. However, it turns out there are even more differences, and rather critical ones.

In an effort to prevent extending this particular article to unnecessarily epic lengths, I’m going to simply point out the fact that after that standing up part, there are still a bunch of other things that need to happen in the snatch and clean. In the deadlift, you just put the weight back down.

Remember—the starting position and first pull of the snatch and clean serve one purpose: to optimize the second pull of the lift, the part during which the athlete is actually generating the overwhelming majority of the acceleration of the bar. In other words, it’s first and foremost a positioning movement for another, more important movement. You’ll notice this point has now been repeated a number of times—pay attention.

The deadlift, on the other hand, is nothing more than a slow and boring first pull—about as simple and straightforward as an exercise can possibly get. Get yourself balanced, hold on tight, and stand up. It’s entirely self-contained, and what happens before and after doesn’t matter.

In addition to this little pearl, we need to keep in mind that whatever weights an athlete—no matter how powerful and technically proficient—is snatching and cleaning, he or she is capable of deadlifting significantly more, even if that athlete rarely or never trains the deadlift directly. This being the case, it should be obvious that what may be deemed unavoidable in a maximal effort deadlift will not necessarily be such in a snatch or clean, maximal or otherwise.

Shoulders, Hips and Feet, Oh My!

In a heavy deadlift, the body will naturally position itself and relate itself to the bar in whatever manner is necessary to move that bar. For example, we can roll the bar six inches forward of our toes and initiate the lift from there, but I can assure you that before the bar separates from the platform, it will have first rolled back over the feet to at least the most forward point at which we can apply upward force without falling over (about the balls of the feet, as it happens), or we will have stepped forward to place the feet under the bar.

Similarly, we can sit in behind the bar with our shoulders behind it, and consequently the arms behind vertical, and tug on the bar all we want. However, it won’t go anywhere other than into our shins until the body readjusts itself into a position in which the arms’ attachments to the torso have aligned themselves above the bar.

These adjustments are wholly natural because they’re necessary to initiate the bar’s separation from the ground. We don’t need to intentionally place ourselves in any special position to execute this separation—all we need to do is not allow ourselves to fall over while pulling on the bar.

The important point of all this is simple: a maximal deadlift is literally a full-body maximal effort, and as such, we have little to no control over the position our bodies assume when executing it—it will always place itself in whatever position it finds most likely to allow completion of the lift, and the degree to which that position strays from our intended one will be commensurate to the amount of weight we’re trying to move.

This is an important distinction between the deadlift and the snatch and clean. Because, as we’ve said previously, snatch and clean weights will always be considerably lower than deadlift weights, we’re still within the realm of postural control from which the maximal deadlift departs. That is, even with a maximal effort clean, an athlete will still be able to a large degree to control the position from which he or she pulls the bar from the floor—this includes things like relative hip and shoulder height and the extension of the back.

If we tell ourselves that the first pull of the snatch and clean are identical to that of the deadlift (or should be), we would quite naturally be compelled to follow the rules of the deadlift. Those rules, as we now understand, are simple: whatever works to move the weight. Never in the history of maximal effort deadlifts has there been an extended spine—a rounded back is the hallmark of a truly heavy deadlift, and to at least some degree, is unavoidable under such weights. So should we perform all of our deadlifts—and our snatches and cleans—with a rounded back intentionally?

Similarly, in a maximal effort deadlift, no matter the starting position of the hips, they will assuredly rise faster than the shoulders and wind up in a higher position, unless started at a height at which the knees are nearing full extension. This phenomenon is quite simple: in a low-hipped position, the angle of the knee is such that its mechanics are quite disadvantaged—that is, it’s very difficult to extend the knee under the full load. Because the body knows what to do, it will naturally begin extending the knees with minimal bar movement until the angle of the knee is such that it can bear the full load and begin moving the barbell along with the rest of the body. This is a very obvious adjustment to relieve the legs (meaning the quads) of some of the work and shift more of it to the back and hips—in the weightlifting world commonly referred to as unloading the legs. It has nothing to do with the arms, shoulders, 12-sided dice, or anything else—it has to do exclusively with the fact that in such an instance, the quads are not strong enough to move the weight. The solution? Strengthen the correct positions and movement.

Try it Again. This Time with Feeling.

We can talk about this all we want, and no matter how articulate, charming and witty I may be, the best way to convince you that this starting position is the most effective is for you to experience that effectiveness yourself.

So my humble suggestion is this—try it. A radical idea, I know. But it turns out you haven’t earned an argument if you haven’t genuinely evaluated this method.

This is a simple experiment, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. If this is not your current starting position, you’re going to have to actually learn to do it properly—including developing the requisite strength—before the evaluation process can begin. Don’t come tell me it didn’t work for you if you can’t even do it correctly.

A high-hipped, shoulders-a-mile-over-the-bar, bar-over-mid-foot starting position is remarkably easy to learn and immediately put into practice—this is, in my opinion, the primary reason it’s become more popular among those unexposed to the weightlifting community. The fact of the matter is, the first pull is actually quite difficult technically—it’s no easy task to navigate the knees while maintaining correct posture, balance and bar position—and quite difficult in terms of strength. Beginning with the hips higher and the knees more extended eliminates the bulk of these complications by eliminating the bulk of the knee extension from the movement and creating a movement dominated by hip extension. This can quickly get novice lifters performing more successfully by avoiding a part of the lift that creates problems for them, and often problems that manifest in later parts of the lift. In other words, it appears upon a glance to improve lifting technique.

But I can’t do it!

That’s because you have little girly quads and need to do more grown-up squats and pulls. This more upright pulling posture demands much greater quad strength than the high-hipped start, and consequently, if your quads are not strong enough, you won’t be able to maintain such a posture as the load increases. This doesn’t mean you’re beyond hope—it just means you need to adjust your training accordingly and shore up the weak spots instead of giving up, crying about it, and sticking your ass back up in the air.

Let’s Get Serious. For Reals.

Now that we know what a good starting position and first pull should look like, the question is, does it always happen like that with technically proficient lifters? Not exactly.

The fact is, advanced lifters are fighting the same forces with the same anatomy novice lifters are, and at maximal weights they’re subject to experiencing the same problems, just to lesser degrees because of their greater experience and strength specificity. For example, the heavier their weights get, the more their bodies will want to unload their legs and shift the hips up—the difference is that those shifts are much smaller, and they’re lifting way more weight than you are.

And having said that, there is a fairly broad range of abilities even at more advanced levels of weightlifting. I can quickly point out a number of top American lifters, for example, who have trouble maintaining such pulling postures, but who remain successful on the national level because, despite this problem, they’re still excellent athletes, and typically very strong. That said, none of our lifters currently rank with the leaders of the international weightlifting community. Granted this is due overwhelmingly to the differences in drug testing (and consequently use), but this simply means there’s a strength and power disparity, and our international counterparts with that greater strength are able to execute excellent technique farther up the loading scale because that technique requires technique-specific strength to execute.

This is not a confusing concept. We can ask a weak little kid to deadlift 50 kg and watch his back round unavoidably under the load. Does this prove to us that no one can lift more than 50 kg while maintaining spinal extension? Of course not; it demonstrates that this kid needs to get stronger. If we get that kid’s best deadlift to 100 kg, we’ll find that 50 kg goes up with perfect pulling posture.

One can go poke around the internet and find videos showing relatively advanced weightlifters (i.e. some of the Americans I alluded to earlier) executing lifts with significant hip-leading and make claims about this position being ultimately unavoidable, so it’s only logical to simply start there for the sake of efficiency. Since we already know how efficiency factors into this, let’s move on.

It’s important to keep in mind that in reality, there’s really no way to prove a claim—only to disprove one. All it takes is a single example that defies that claim to prove that it’s untrue. One need only look at some more videos to see—quite quickly—that such claims regarding the unavoidability of this high-hipped position are wholly unfounded.

The former videos are simply examples of somewhat less developed technique and correspondingly less developed position-specific strength. The less strength an athlete has specific to the movement in question, the sooner on the loading scale he or she will depart from the desired positions. There is no magic point on that scale beyond which maintaining this posture is impossible—the argument should instead be for improving the athlete’s strength in the necessary positions instead of abandoning a more technically difficult movement demanding of greater technique-specific strength in favor of a simplified version that ultimately limits one’s potential performance.

Further, the idea that this upright pulling posture is so common simply because it’s tradition is an argument overwhelmingly void of merit. Tradition is not by its nature flawed, and in fact, can be the result of certain practices being established over time as the most effective. If the weightlifting community as a whole has over the years of technique evolution gravitated to a specific set of pulling rules with little variation, it’s not an accident—it’s a product of coaches and athletes actively involved in the sport continually searching for the best possible methods of snatching and clean & jerking, and continuing to refine those methods through experimentation with their athletes. And of course, it seems somewhat silly to state that things are done in such a way simply because “they’ve always been done that way” when there have been dramatic changes in snatch and clean & jerk technique over the years—the claim is entirely baseless.

Finally, the idea that the best coaches and athletes involved in a sport are disinclined to use whatever works best, despite convention, is utter nonsense, and to suggest otherwise is not only terribly presumptuous, but arrogant, pretentious, insulting to every legitimate coach and athlete in the community, and indicative of a remarkable failure to understand the sport in general and its lift technique specifically.

I’m not even going to make you do your own internet poking for photos and videos—we can disprove the notion that departing from an upright pulling posture, at any point in the lift, is unavoidable with a couple photos:

That’s 2008 superheavyweight Olympic gold-medalist Matthias Steiner of Germany. In that photo, he’s snatching over 200 kg (440 lbs). Notice the angle of his back and the orientation of his arms—and that’s with the bar all the way up at knee-height, the point by which it’s been claimed one will unavoidably shift to the back angle associated with the high-hipped, shoulders-forward start. Since this lift is among the heaviest snatches ever performed, it seems fairly clear that it is not, in fact, impossible to maintain such a posture, even at the heaviest loading.

Matthias Steiner demonstrating excellent pulling technique. Notice how little

his back angle shifts during the lift, despite an extremely upright initial posture.

Throughour the pull, his arms deviate from a vertical orientation only minimally.

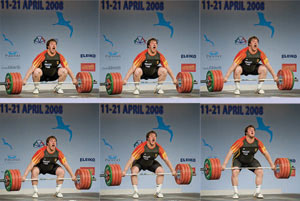

The following photo is of Taner Sagir initiating a snatch of at least 160 kg—and at a bodyweight of only 77 kg. To be clear, we’re looking at a more than double bodyweight snatch—that is, an extremely heavy weight in the lift that requires the lowest starting position in terms of the hips and shoulders. And look at that—with the bar a couple inches off the floor, Sagir has managed to maintain his upright posture with the arms oriented approximately vertically.