Lessons from Romania

Nicu Vlad is one of the greatest weightlifters of all time. The Romanian legend won the Olympic gold medal at the 1984 Los Angeles games when he was only twenty-one years old, and that was only the beginning of his amazing career. Vlad went on to win the silver medal at the 1988 Olympics, the bronze at the 1996 Olympics (when he was thirty-three), and three world championships in 1984, 1986, and 1990. However, the accomplishment that Vlad is probably most famous for is his all-time world record snatch of 200.5 kilos in the old 100 kilo bodyweight class. He is the heaviest lifter in history to snatch double bodyweight, and many weightlifting experts believe that Vlad is one of the most technically perfect weightlifters of all time. His snatch technique has been the learning model for thousands of young weightlifters over the last two decades. So you can imagine how I felt when I found out that I was going to have the opportunity to train with Vlad for three weeks at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs during the summer of 1990.

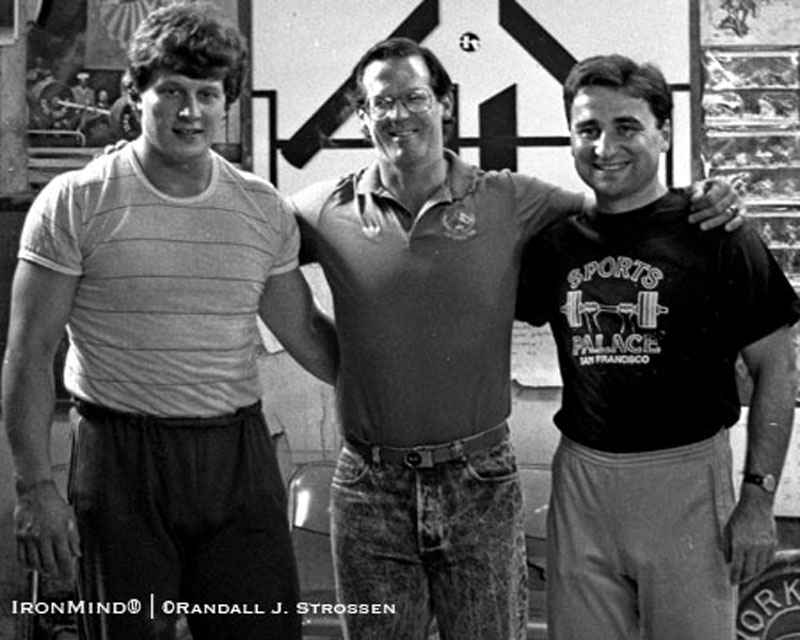

Nicu and his coach, Dragomir Cioroslan, came to the United States in 1990 to spend the summer training at various locations around the country. They spent most of this visit in Colorado Springs, and the national junior squad training camp was held at the OTC during the same time. I was invited to train at this camp, which meant that I was going to be working out in the same gym with an athlete whose pictures I had taped up on the walls of the gym where I worked out at home. I was seventeen years old and Nicu Vlad had been my weightlifting idol long before I knew he was coming to the United States. This was literally the opportunity of a lifetime, and this article will examine just a fraction of the many lessons I learned during that memorable summer.

First, the formal details of training…

I recall meeting Dragomir and Nicu for the first time. Dragomir, who was one of the friendliest people I had ever met in my life, smiled broadly and shook my hand with gusto as he looked me in the eye and exclaimed, “My name is Dragomir, how are you?!” After that, I was introduced to the big man, who shook my hand with his thick paw and growled, “Nicu Vlad,” as he glanced at me with the same interest he probably showed in his morning bowel movement. Nicu was polite and respectful, but he had a quiet intensity in his personality that was obvious. This man was a legend, and everybody knew it. You gave him a wide berth.

Nicu usually trained twice a day, and his workouts were broken up into short segments. He generally performed the classic lifts along with front squats, back squats, and RDLs (more on that later). I never saw him spend any time doing supplemental exercises such as push presses, overhead squats, etc. He often performed his squats in the mornings and his competition lifts in the afternoons. In a typical afternoon session, he would train one of the competition lifts (snatch or clean and jerk) for around thirty minutes and then go outside the gym to lie down in the grass and relax for a while. After twenty or thirty minutes, he would come back in the gym to train again, often hitting the other competition lift. After this second session, he would sometimes go back outside to take another relaxation break before the next segment or sometimes he would go straight into a squatting or pulling movement, depending on which lifts he had trained that morning. Basically, Dragomir had him on a European-style program that combined many of the Russian and Bulgarian principles that we have all studied over the years. He was training around seven to nine times per week, with the morning sessions usually taking place around ten o’clock and the afternoon sessions around three or four. It’s important to note that Nicu was twenty-seven years old during this time, which is generally considered a little old for most hardcore European training systems. I believe his volume and exercise selection had been narrowed to accommodate his age.

Nicu was training to compete at the 1990 Goodwill Games in Washington at the end of the summer, so I was able to see him train when he was around six weeks out from a meet. The top lifts I saw him perform in training during this time are as follows: 185 snatch, 210 clean and jerk (he clean and jerked 210, brought the weight down to his shoulders, and jerked it a second time). Nicu’s all-time best official lifts are 200.5 in the snatch and 237.5 in the clean and jerk. But those lifts had been done in 1986; during the 1990 time period when I saw him, he was usually hitting around 190/220 in meets. Therefore, 185 and 210 were working pretty close to his top results at the time. In the supplemental lifts, I saw multiple sets of three in the back squats with 250-260, and RDL sets of three usually performed with 250-260. The squats and RDLs with 260 were, as far as the eye could tell, practically effortless. He did not squat with any of the massive weights that many Americans think the top European lifters handle on a daily basis. Also, the jerk was his weak spot and, because of this, he almost always lowered the weight to his shoulders and performed two reps of the jerk for every clean.

But despite the amazing work capacity and kilograms Nicu was capable of handling, the most phenomenal aspect of his training was definitely his technique. When I first became an Olympic weightlifter, a great coach told me that one of the elements of having perfect technique meant you could “make 50 kilos look exactly the same as 150 kilos.” Vlad was the best example of this rule that I have ever seen in my career. Every movement of his body from his back position to his foot placement to his acceleration in the second pull was identical, regardless of the weight on the bar. When he performed snatches and cleans, he would usually power snatch or power clean the light weights, catching them in a high receiving position. And, as the weight got progressively heavier, he would simply catch the bar gradually lower and lower until he was hitting his top weights and catching them near rock-bottom. Nicu jumped his feet forcefully off the platform when he was extending the second pull and going under the bar, producing a loud slap! when his feet hit the platform as he turned his wrists over and caught the weight. Not every great lifter has utilized the same “feet jumping” technique as Vlad, obviously. There are some great lifters who simply lift their feet just high enough to slide them out and re-position them as they receive the bar. But Vlad’s technique involved violent jumping of the feet and many lifters, including myself, formed their own technique from emulating him. Everything about his movements was a textbook combination of speed, tightness, precision, and strength. Any weightlifter who wants to be successful would be wise to study the technique of Nicu Vlad, as we all did during our summer of watching him train.

A quick 185 snatch, then some RDLs…

One afternoon, many of the junior squad lifters were in the OTC game room playing pool and PacMan when Wes Barnett stuck his head in the door and told everybody, “Vlad’s going heavy in his workout.” We all ran out of the game room, across the hockey field, and down the hill to the gym so we could see some big weights. Nicu was warming up in the snatch at the time, and we all quietly took seats around the gym to watch the big show. After his normal warm up, snatching 70, 90, 110, 130, 140, 150, and 160 with ease, he put 170 on the bar. We were all shocked to see him miss the 170, but then he repeated the weight a few minutes later and made it easily. He jumped to 175 and missed the weight behind him twice, and then jumped to 180 and missed that weight twice as well. Most of us were wondering what in the hell was going on, as he was clearly in good shape and strong enough to make these weights. I will never forget what he did next.

He loaded 185 on the bar. This time, as he stood in front of the bar preparing for the lift, he stood motionless, tilted his head back and closed his eyes in the famous Vlad-concentration pose we had all seen him strike on the platform at the Olympics and world championships. He had not done this before any of the other lifts of his workout, and the gym went completely silent. After ten seconds, he reached down, grabbed the bar, and nailed the easiest, strongest snatch of the day.

I learned a lot about mental discipline as I watched this workout. After his missed snatch attempts, Nicu had no reaction whatsoever. He did not get visibly upset or discouraged in any way. His face remained stoic and he simply progressed to the next weight, confident that he would make any technical corrections that were needed. When he got to 185, which I later learned was the weight he had planned to hit that day, he just applied an extra level of concentration and focus. It was a big weight, he was having a bad workout, and he needed to tap into his extra reservoir of inner strength, mojo, or whatever you want to call it. Because he was a world champion, his mojo did not involve jumping around like a crackhead, punching himself in the face, or kicking the bar. His fire burned inside, and it burned hot. And after he made the 185, he simply went on with the rest of his workout. No celebration, actions of deep relief, or pissing and moaning because he hadn’t had a perfect workout. It was all just a day at the office for Nicu Vlad.

Then he started performing an exercise we saw him do regularly. It looked a lot like a stiff-legged deadlift, only he bent his knees slightly and displaced his hips backwards as he lowered the bar. He would regularly do this exercise with 250 kilos or more, and he even did a personal record set of 300x3 at the end of the camp. Somebody in the gym asked Nicu and Dragomir what the exercise was called. They said that they did not have a special name for it, and so one of the American lifters suggested that it could be called a “Romanian Deadlift” or RDL. Now, here we are eighteen years later, and this exercise has become a common staple in workout routines all across this country. I’ve always considered it a privilege that I was present when the RDL was officially named.

The Nicu Vlad Charm School…

Vlad had a fairly quiet, reserved personality, probably due mostly to the fact that his English at the time was relatively limited. With the English that he was able to speak, he was always happy to engage in conversation and joke around. I recall one night in the OTC dorm when a tall swimmer was walking down the hall and accidentally bumped into Nicu, knocking him back a step. The swimmer apparently thought he was a tough guy, because he just glanced around and kept walking without excusing himself. Wes Barnett jokingly told Nicu to go give the guy a beating. Nicu looked at Wes and shook his head saying, “What?” because he didn’t understand. Wes pointed at the swimmer and punched his fist into his palm five or six times. Nicu understood, but he stopped Wes and said, “No.” Then he punched his own fist into his palm one time, looked at Wes and said, “Just one.” He was telling us that he could knock the guy out with one shot!

Nicu also gave out a piece of advice that I now realize is probably the greatest lesson I’ve ever learned in weightlifting and life in general. This particular junior squad camp had several young athletes who would later go on to become great American lifters in the 1990s. Names like Barnett, Gough, McRae, Patao, and my dorm roommate Pete Kelley were all there. These individuals were hard working, driven, competitive animals who were hungry to move up in the national rankings. However, there were also several young athletes who had made the junior squad and earned their way to the camp, but showed some of the worst attitudes I have seen in my years as an athlete. These were spoiled brats who whined constantly about the gym being too small, the bars not spinning well enough, the dorms being too hot, the taste of the dining hall food, and every other free benefit that had been given to them. They did not train hard, complained incessantly, back-talked the coaches and OTC staff, and threw temper tantrums in the gym when they missed lifts. Not surprisingly, almost all of them quit the sport within the next few years.

Nicu and Dragomir used to watch these kids silently and shake their heads in disgust. It was obvious what they were thinking. Then, USA Weightlifting magazine decided to do an interview with Vlad, so Dragomir acted as his interpreter to answer their questions. At one point, the reporter asked Nicu what he thought about training with our top young junior lifters. Although I’m not quoting him word-for-word, I remember his answer clearly and it was this: “In Romania, I train on a bar that is bent. My gym has bad lighting and very little heat in the winters. Here in America, you have everything you need to train. It’s not in the bar or the gym or the platform… it’s in you.”

The message, which I consider almost a biblical principle, is that the strength you possess in your heart will be the deciding element in your weightlifting career. Adversity is the name of the game in this sport, and the only factor that can propel an athlete to success is sheer force of will. Physical talent is not enough. There are armies of physically talented athletes out there. The ones like Nicu Vlad, who refuse to allow anything to defeat them, will be the last ones standing. This attitude drove Nicu forward to victory at the World Championship that same year, and then eventually to the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where, at the age of thirty-three, he snatched 197.5 in the 108 class, winning the third Olympic medal of his illustrious career.

I could write an entire book about all the other things I saw, heard, and learned during those weeks. Vlad told us that Yuri Zacharevich from the Soviet Union had rack jerked 300 kilos in training. Vlad told us that Naim Suleymanoglu owned eight houses in Turkey. Vlad told us that we were all idiots for spending our recovery time having chicken fights in the OTC pool instead of resting for our next workout. During his trip, somebody printed up some “Nicu Vlad Summer US Tour 1990” tank tops and sold them. I bought one and wore it as religiously as the stoners at my high school wore their Megadeth t-shirts. It was an exciting summer that marked the beginning of some great US lifting careers. I was lucky to be there. We all were.

Nicu and his coach, Dragomir Cioroslan, came to the United States in 1990 to spend the summer training at various locations around the country. They spent most of this visit in Colorado Springs, and the national junior squad training camp was held at the OTC during the same time. I was invited to train at this camp, which meant that I was going to be working out in the same gym with an athlete whose pictures I had taped up on the walls of the gym where I worked out at home. I was seventeen years old and Nicu Vlad had been my weightlifting idol long before I knew he was coming to the United States. This was literally the opportunity of a lifetime, and this article will examine just a fraction of the many lessons I learned during that memorable summer.

First, the formal details of training…

I recall meeting Dragomir and Nicu for the first time. Dragomir, who was one of the friendliest people I had ever met in my life, smiled broadly and shook my hand with gusto as he looked me in the eye and exclaimed, “My name is Dragomir, how are you?!” After that, I was introduced to the big man, who shook my hand with his thick paw and growled, “Nicu Vlad,” as he glanced at me with the same interest he probably showed in his morning bowel movement. Nicu was polite and respectful, but he had a quiet intensity in his personality that was obvious. This man was a legend, and everybody knew it. You gave him a wide berth.

Nicu usually trained twice a day, and his workouts were broken up into short segments. He generally performed the classic lifts along with front squats, back squats, and RDLs (more on that later). I never saw him spend any time doing supplemental exercises such as push presses, overhead squats, etc. He often performed his squats in the mornings and his competition lifts in the afternoons. In a typical afternoon session, he would train one of the competition lifts (snatch or clean and jerk) for around thirty minutes and then go outside the gym to lie down in the grass and relax for a while. After twenty or thirty minutes, he would come back in the gym to train again, often hitting the other competition lift. After this second session, he would sometimes go back outside to take another relaxation break before the next segment or sometimes he would go straight into a squatting or pulling movement, depending on which lifts he had trained that morning. Basically, Dragomir had him on a European-style program that combined many of the Russian and Bulgarian principles that we have all studied over the years. He was training around seven to nine times per week, with the morning sessions usually taking place around ten o’clock and the afternoon sessions around three or four. It’s important to note that Nicu was twenty-seven years old during this time, which is generally considered a little old for most hardcore European training systems. I believe his volume and exercise selection had been narrowed to accommodate his age.

Nicu was training to compete at the 1990 Goodwill Games in Washington at the end of the summer, so I was able to see him train when he was around six weeks out from a meet. The top lifts I saw him perform in training during this time are as follows: 185 snatch, 210 clean and jerk (he clean and jerked 210, brought the weight down to his shoulders, and jerked it a second time). Nicu’s all-time best official lifts are 200.5 in the snatch and 237.5 in the clean and jerk. But those lifts had been done in 1986; during the 1990 time period when I saw him, he was usually hitting around 190/220 in meets. Therefore, 185 and 210 were working pretty close to his top results at the time. In the supplemental lifts, I saw multiple sets of three in the back squats with 250-260, and RDL sets of three usually performed with 250-260. The squats and RDLs with 260 were, as far as the eye could tell, practically effortless. He did not squat with any of the massive weights that many Americans think the top European lifters handle on a daily basis. Also, the jerk was his weak spot and, because of this, he almost always lowered the weight to his shoulders and performed two reps of the jerk for every clean.

But despite the amazing work capacity and kilograms Nicu was capable of handling, the most phenomenal aspect of his training was definitely his technique. When I first became an Olympic weightlifter, a great coach told me that one of the elements of having perfect technique meant you could “make 50 kilos look exactly the same as 150 kilos.” Vlad was the best example of this rule that I have ever seen in my career. Every movement of his body from his back position to his foot placement to his acceleration in the second pull was identical, regardless of the weight on the bar. When he performed snatches and cleans, he would usually power snatch or power clean the light weights, catching them in a high receiving position. And, as the weight got progressively heavier, he would simply catch the bar gradually lower and lower until he was hitting his top weights and catching them near rock-bottom. Nicu jumped his feet forcefully off the platform when he was extending the second pull and going under the bar, producing a loud slap! when his feet hit the platform as he turned his wrists over and caught the weight. Not every great lifter has utilized the same “feet jumping” technique as Vlad, obviously. There are some great lifters who simply lift their feet just high enough to slide them out and re-position them as they receive the bar. But Vlad’s technique involved violent jumping of the feet and many lifters, including myself, formed their own technique from emulating him. Everything about his movements was a textbook combination of speed, tightness, precision, and strength. Any weightlifter who wants to be successful would be wise to study the technique of Nicu Vlad, as we all did during our summer of watching him train.

A quick 185 snatch, then some RDLs…

One afternoon, many of the junior squad lifters were in the OTC game room playing pool and PacMan when Wes Barnett stuck his head in the door and told everybody, “Vlad’s going heavy in his workout.” We all ran out of the game room, across the hockey field, and down the hill to the gym so we could see some big weights. Nicu was warming up in the snatch at the time, and we all quietly took seats around the gym to watch the big show. After his normal warm up, snatching 70, 90, 110, 130, 140, 150, and 160 with ease, he put 170 on the bar. We were all shocked to see him miss the 170, but then he repeated the weight a few minutes later and made it easily. He jumped to 175 and missed the weight behind him twice, and then jumped to 180 and missed that weight twice as well. Most of us were wondering what in the hell was going on, as he was clearly in good shape and strong enough to make these weights. I will never forget what he did next.

He loaded 185 on the bar. This time, as he stood in front of the bar preparing for the lift, he stood motionless, tilted his head back and closed his eyes in the famous Vlad-concentration pose we had all seen him strike on the platform at the Olympics and world championships. He had not done this before any of the other lifts of his workout, and the gym went completely silent. After ten seconds, he reached down, grabbed the bar, and nailed the easiest, strongest snatch of the day.

I learned a lot about mental discipline as I watched this workout. After his missed snatch attempts, Nicu had no reaction whatsoever. He did not get visibly upset or discouraged in any way. His face remained stoic and he simply progressed to the next weight, confident that he would make any technical corrections that were needed. When he got to 185, which I later learned was the weight he had planned to hit that day, he just applied an extra level of concentration and focus. It was a big weight, he was having a bad workout, and he needed to tap into his extra reservoir of inner strength, mojo, or whatever you want to call it. Because he was a world champion, his mojo did not involve jumping around like a crackhead, punching himself in the face, or kicking the bar. His fire burned inside, and it burned hot. And after he made the 185, he simply went on with the rest of his workout. No celebration, actions of deep relief, or pissing and moaning because he hadn’t had a perfect workout. It was all just a day at the office for Nicu Vlad.

Then he started performing an exercise we saw him do regularly. It looked a lot like a stiff-legged deadlift, only he bent his knees slightly and displaced his hips backwards as he lowered the bar. He would regularly do this exercise with 250 kilos or more, and he even did a personal record set of 300x3 at the end of the camp. Somebody in the gym asked Nicu and Dragomir what the exercise was called. They said that they did not have a special name for it, and so one of the American lifters suggested that it could be called a “Romanian Deadlift” or RDL. Now, here we are eighteen years later, and this exercise has become a common staple in workout routines all across this country. I’ve always considered it a privilege that I was present when the RDL was officially named.

The Nicu Vlad Charm School…

Vlad had a fairly quiet, reserved personality, probably due mostly to the fact that his English at the time was relatively limited. With the English that he was able to speak, he was always happy to engage in conversation and joke around. I recall one night in the OTC dorm when a tall swimmer was walking down the hall and accidentally bumped into Nicu, knocking him back a step. The swimmer apparently thought he was a tough guy, because he just glanced around and kept walking without excusing himself. Wes Barnett jokingly told Nicu to go give the guy a beating. Nicu looked at Wes and shook his head saying, “What?” because he didn’t understand. Wes pointed at the swimmer and punched his fist into his palm five or six times. Nicu understood, but he stopped Wes and said, “No.” Then he punched his own fist into his palm one time, looked at Wes and said, “Just one.” He was telling us that he could knock the guy out with one shot!

Nicu also gave out a piece of advice that I now realize is probably the greatest lesson I’ve ever learned in weightlifting and life in general. This particular junior squad camp had several young athletes who would later go on to become great American lifters in the 1990s. Names like Barnett, Gough, McRae, Patao, and my dorm roommate Pete Kelley were all there. These individuals were hard working, driven, competitive animals who were hungry to move up in the national rankings. However, there were also several young athletes who had made the junior squad and earned their way to the camp, but showed some of the worst attitudes I have seen in my years as an athlete. These were spoiled brats who whined constantly about the gym being too small, the bars not spinning well enough, the dorms being too hot, the taste of the dining hall food, and every other free benefit that had been given to them. They did not train hard, complained incessantly, back-talked the coaches and OTC staff, and threw temper tantrums in the gym when they missed lifts. Not surprisingly, almost all of them quit the sport within the next few years.

Nicu and Dragomir used to watch these kids silently and shake their heads in disgust. It was obvious what they were thinking. Then, USA Weightlifting magazine decided to do an interview with Vlad, so Dragomir acted as his interpreter to answer their questions. At one point, the reporter asked Nicu what he thought about training with our top young junior lifters. Although I’m not quoting him word-for-word, I remember his answer clearly and it was this: “In Romania, I train on a bar that is bent. My gym has bad lighting and very little heat in the winters. Here in America, you have everything you need to train. It’s not in the bar or the gym or the platform… it’s in you.”

The message, which I consider almost a biblical principle, is that the strength you possess in your heart will be the deciding element in your weightlifting career. Adversity is the name of the game in this sport, and the only factor that can propel an athlete to success is sheer force of will. Physical talent is not enough. There are armies of physically talented athletes out there. The ones like Nicu Vlad, who refuse to allow anything to defeat them, will be the last ones standing. This attitude drove Nicu forward to victory at the World Championship that same year, and then eventually to the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where, at the age of thirty-three, he snatched 197.5 in the 108 class, winning the third Olympic medal of his illustrious career.

I could write an entire book about all the other things I saw, heard, and learned during those weeks. Vlad told us that Yuri Zacharevich from the Soviet Union had rack jerked 300 kilos in training. Vlad told us that Naim Suleymanoglu owned eight houses in Turkey. Vlad told us that we were all idiots for spending our recovery time having chicken fights in the OTC pool instead of resting for our next workout. During his trip, somebody printed up some “Nicu Vlad Summer US Tour 1990” tank tops and sold them. I bought one and wore it as religiously as the stoners at my high school wore their Megadeth t-shirts. It was an exciting summer that marked the beginning of some great US lifting careers. I was lucky to be there. We all were.

|

Matt Foreman is the football and track & field coach at Mountain View High School in Phoenix, AZ. A competitive weightliter for twenty years, Foreman is a four-time National Championship bronze medalist, two-time American Open silver medalist, three-time American Open bronze medalist, two-time National Collegiate Champion, 2004 US Olympic Trials competitor, 2000 World University Championship Team USA competitor, and Arizona and Washington state record-holder. He was also First Team All-Region high school football player, lettered in high school wrestling and track, a high school national powerlifting champion, and a Scottish Highland Games competitor. Foreman has coached multiple regional, state, and national champions in track & field, powerlifting, and weightlifting, and was an assistant coach on 5A Arizona state runner-up football and track teams. He is the author of Bones of Iron: Collected Articles on the Life of the Strength Athlete. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date