Applying Motor Learning Research for Athletes

In our own training and as coaches, we are always looking for the optimal learning strategies for enhancing performance. The science and practice of motor skill learning has provided very interesting discoveries over the past 30 years, which has often resulted in previously common methods of teaching and practice being debunked.

One of the problems with coaching is the natural tendency to focus on the immediate changes in skill. This seems logical; if your athlete is performing the new skill well in the current session, then you must be doing something right! And maybe you are, but as we’ll show, you may be actually hindering their overall growth.

We can all agree that we are seeking the long-term retention of skill and increased performance for our athletes. Research tells us that there can be quite a difference between the performance within a training session and the retention of that performance over a period of time.

This is something that we see in the trenches as well. We’ve all known or had athletes that performed well in the gym and in training, but had less than stellar success in competition. Beyond psychosomatic issues, there may be some factors in the training itself that contribute to performance issues.

Let’s take a look at the major concepts of enhanced motor learning and how they may differ from standard coaching. We’ll also outline an example of real-life programming that takes advantages of best practice methods from research.

Schema

The following concepts are primarily derived from the research of Richard Schmidt (Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis) whose Schema Theory of motor learning was quite contrary to established theories and practice.

The theory states that we create generalized motor programs (GMP) for certain movement patterns we perform, and these programs are foundations for newly learned skills. The GMP contain parameters based on the sensory information from the body during the movement, the particular (muscle) actions generated to engage in the movement, and the sensory changes and outcome following those particular actions.

Essentially, it means that with every repetition of a movement skill, our bodies gather feedback to modify and improve the motor program. Each repetition and practice of a skill is a chance to improve. However, this doesn’t mean that we should be striving to achieve a “perfect” repetition in every training session.

What?! How does that make any kind of sense? Haven’t we all heard people say, “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect”? Well, it appears that they are wrong. In fact, the best methods of learning allow errors in practice, and it is the self-awareness of these errors and the subsequent changes that encourage the best progress. Let’s delve into why this is the case.

Feedback

A common coaching tactic is to provide immediate feedback after a mistake or break in technique by the athlete. “Elbows higher! Lift your chest up!” The results of which are easily seen; a good athlete listens to their coach and attempts to change their form and seemingly “gets better.”

And this is absolutely shown in research, when what is termed Knowledge of Results (KR), the feedback given immediately after (or even during) a skill, performance in that session is consistently better. And when KR is delayed, performance suffers. This seems logical; of course you’ll do better when you are observed and coached on correcting your errors as soon as you make them.

But, although short-term performance is better, when skills are measured in later sessions, it was the delayed KR group that had better retention of skill than those with immediate KR. Those people had better performance within practice, but ended up with a deterioration of performance below the delayed feedback group.

Why would this be so? The theory is that the coach’s immediate feedback interferes with the brain’s information processing of all the sensory and motor pattern reactions during and after the skill performance. The learning that would have happened was interrupted by the coaching.

In essence, immediate feedback is a crutch upon which the athlete becomes unknowingly dependent.

Bandwidth

Bandwidth refers to the error tolerance allowed the athlete in their skill training session. A narrow bandwidth means less tolerance before feedback is given to correct the issue. A wide bandwidth gives more leeway before telling the athlete to change technique.

Having less error tolerance allows for fewer mistakes in the practice session, and predictably leads to improved performance in the skill. It has to be that way because the coach isn’t allowing mistakes!

However, as shown in the feedback research, a narrow window of acceptable performance leads to poorer retention of skills versus a wider bandwidth, which allows more deviations from “perfect” technique.2

It’s thought that the too restrictive of a learning session deters the motor learning process.

Practice Arrangement

Blocked practice refers to the method of teaching wherein the same task is repeated before moving on to another drill; for example, shooting a basketball from the free throw line 50

times in a row, or hitting half a bucket of balls with your 9 iron before hitting the rest with your driver.

Random practice is just as it sounds, you have several tasks in your practice session and the sequencing is varied so that you aren’t performing the same drill again and again.

Just as with immediate feedback, it seems intuitively correct to practice one skill over and over to attain a mastery of the movement. And similarly, you will see an improved practice performance in the session. Yet again, when measured in the long term, random practice outperforms blocked practice.1

Here, it may be that the blocked practice is so repetitive and rote that the cognitive processing is diminished. It’s boring! So your brain takes a break even as your body keeps on trucking.

Attentional Focus

Attentional focus refers to what the athlete concentrates upon in the movement skill. An internal focus is directed to the movement itself or the positioning of the body in its performance. External focus has the learner more aware of the effects of the movement outside of the body.

Take the performance of a clean, for example. Internal focus of the skill relates to thinking about your back angle position in the first pull. In contrast, an external focus concentrates on the bar path and how high the pull should be before you move under the bar.

An external attentional focus has been correlated with improved performance both during the practice session and in long-term outcomes. An interesting study showed that giving a learner instruction on the optimal movement pattern prior to the performance of a skill lead to worse performances in the new movement than providing no instruction at all!

This would seem at odds with what’s said above regarding the importance of cognitive processing in motor learning. You’d think that an internal focus on the specifics of body mechanics and movement would help in the creation of a good motor pattern. It’s very counterintuitive that this isn’t the case.

But just as in immediate feedback, narrow bandwidth, and blocked practice methods; an internal focus interferes with learning because information is given too early in the process. In this case, the information is provided by the athlete themselves, and is separate from the information that would be gathered during the performance.

Whole vs Part Practice

Another common teaching method is drilling the athlete with parts of the whole movement pattern, as opposed to the entire skill itself. Again this seems to be a reasonable way of coaching, wherein a complex skill is broken down into more manageable sections, and those sections drilled until the achievement of a satisfactory performance.

One of the more extreme examples of this was when I was watching a friend’s mother taking a golf lesson. The instructor had divided the swing into what seemed to be a dozen different phases, and I’m not sure she was allowed to take a full swing during the entire hour!

Unfortunately, this has been shown to lessen motor learning as well. The separation of a skill into components (no matter how well reasoned) decreased overall performance as compared to practicing the full motor pattern. However, this effect may be ameliorated by using the “whole-part-whole” method , where the skill is practiced in its entirety, then in components, and then finally as a whole again all within the same session.

Real World Application

In our jobs of coaching, and in training ourselves, we should be concerned with performance in the long haul. Immediate improvements are meaningless if these skills are not retained and ably performed in subsequent practices and especially in competition.

Though the research all points towards delayed feedback, wide bandwidth, random practice, external attentional focus, and whole task practice; the realities of training an athlete necessitate a deviation from these ideal methods.

Safety is one of the primary concerns, especially in motor skills that involve implements or body movements that can be dangerous to the athlete. In these cases, the initial learning period should focus on safe performance.

Another concern, which is far from trivial, is the development of an athlete’s confidence. Delayed feedback may be best for long term learning, but if the frustration level rises too high, the practice session can degrade and the athlete will fail to benefit at all. An initial period of building confidence and reducing anxiety can help create quality practice. From there, the methods of allowing mistakes will best be put to use.

Also, it can be difficult to separate the learning of a skill of a particular movement from the actual need for strength of that skill, particularly in gymnastic type actions. In this case, using components as a teaching method is necessary to build the adequate amount of strength. Then moving to whole task learning as soon as possible.

The deliberate allowance of errors in form seems at odds with prevailing views, especially those such as Tommy Kono, with his insistence on Quality Training, where form and technique should be precise and as perfect as possible. However, looked upon from a different angle, they are actually the same approach. A quality performance has to start from somewhere and the errors made in the beginning lead to improved execution down the line. The athlete who is allowed to make an error in learning will become used to employing self-awareness much more quickly than those that are provided with the answers. These athletes have no need to look within when others are telling them exactly what to do.

General Sample Progression

First session

-Assessment of the athlete’s task performance.

-Identify possible dangerous form errors.

-Determine poor flexibility and/or strength deficits in task performance

-These form errors (dangerous, decreased flexibility/strength) will then addressed with specific “part task” practice drills.

-Determine if whole task training can be done safely.

-Engage in whole-part-whole sequencing with blocked practice.

-Feedback in this session can be regular but cue as much as possible on external focus.

Second session

-Repeat assessment of the movement skill.

-Blocked practice of component parts can still be done until strength and other deficit issues remain (especially if safety is still a concern).

-Whole-part-whole practice continues, but chosen part tasks are now randomized.

Third session and beyond

-Component practice tapers away and full skill practice is the emphasis with quality repetitions

-Wide bandwidth and significantly delayed feedback should be the norm, and feedback becomes more in the form of question/answer to encourage errors and the analysis of those errors.

Specific Sample Progression

The Bent Arm Tuck Press to Handstand

First Session

-Demonstrate full movement

-Observe client’s mimicking of the movement and identify:

-Dangerous form errors

-Weakness limitations

-Flexibility limitations

-Examples of dangerous form errors

-Too much of a jump forward can cause a fall onto the head or spine

-Elbows flared can cause undue shoulder strain and poor positioning

-Examples of weakness limitations

-Unable to maintain elbow angle or push up (weak triceps)

-Unable to maintain hips over shoulder position (weak trunk)

-Examples of flexibility limitations

-Wrist pain with weight-bearing (poor wrist extension flexibility)

-If no glaring limitations are seen, then:

-Teach full movement with cueing for:

-Eye gaze is directly at the floor

-Choose one or two internal cues during instruction

-Elbows in

-Shoulders in line with the fingers vertically

-Hips in line with shoulders vertically

-Full movements then taught as:

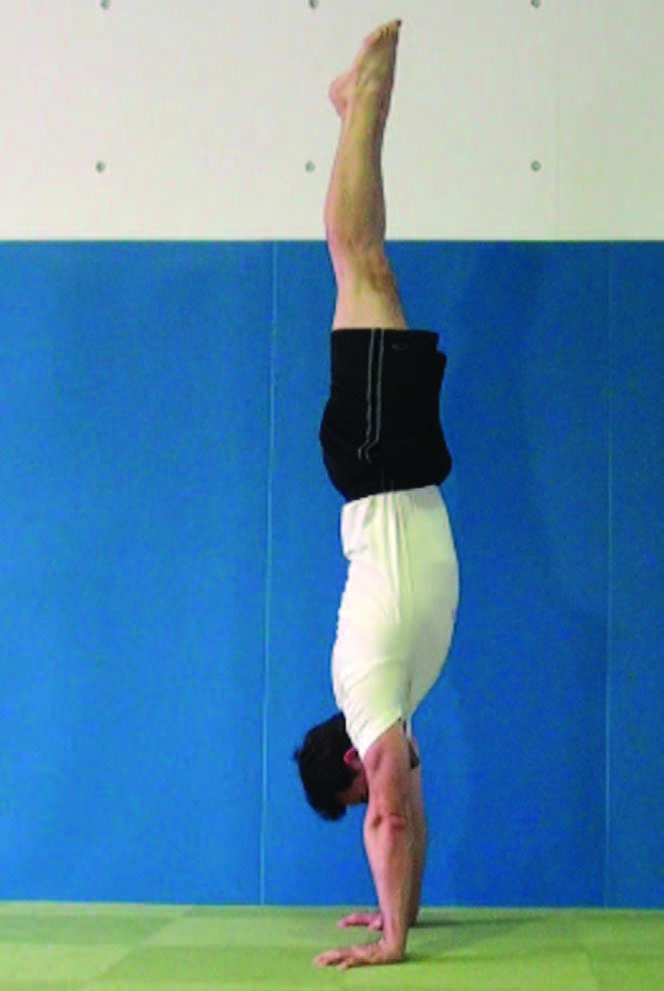

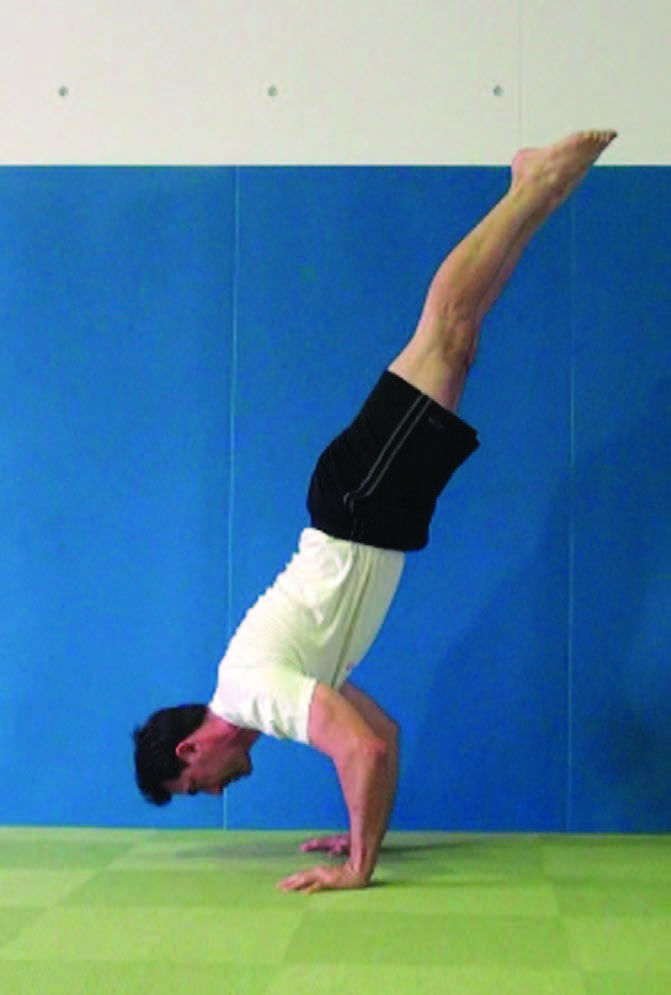

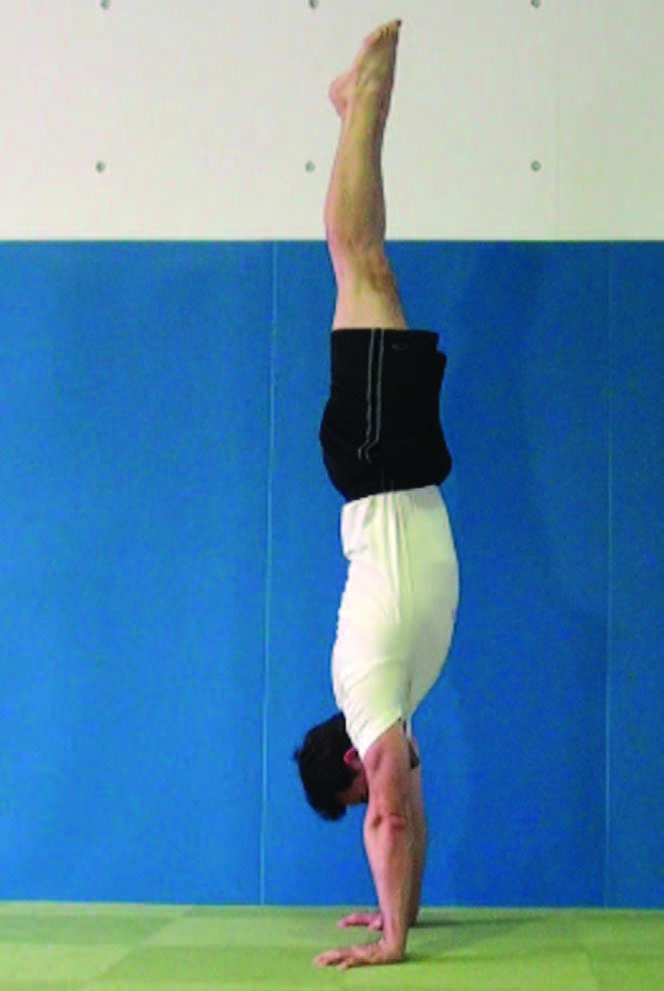

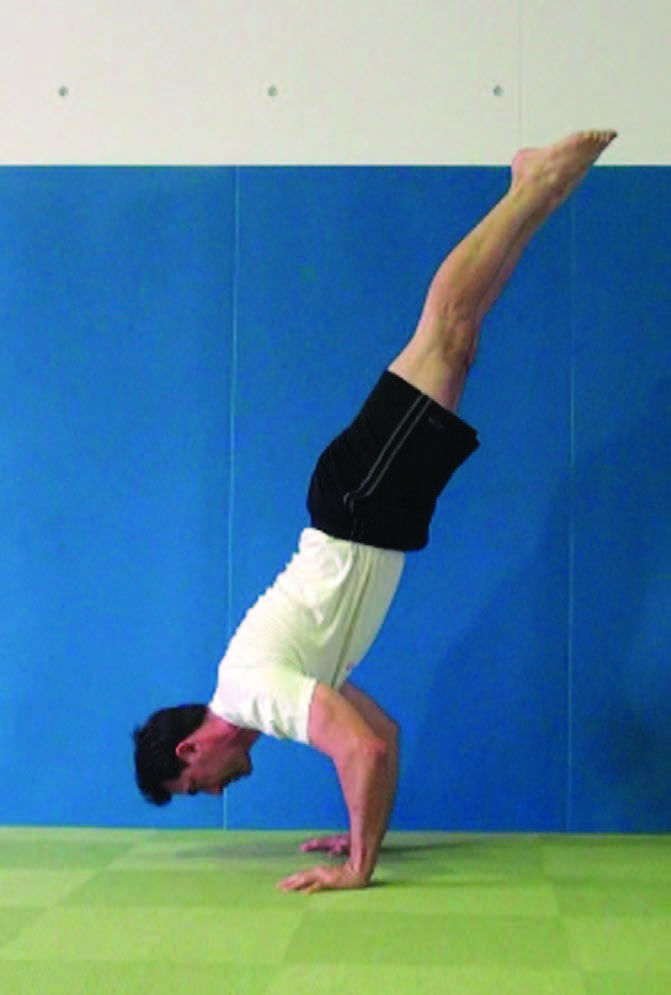

-Bent Arm Low Tuck, extend to Straight Leg and press to Handstand (with momentum)

.jpg)

-If flexibility limitations, then specific stretching prior to whole movement training.

-If weakness then teach one or two of the following components:

-Tripod hold

-Bent arm crane hold

.jpg)

-Bent arm tuck half press and drop legs

-After this part learning, end with full movement for a few repetitions.

Second Session

Full movement taught as:

-Bent Arm Low Tuck, extend to Straight Leg and press to Handstand (strict press)

Following up on weakness limitations, continue components above and remember to end with a few repetitions of the full movement.

Third Session and beyond

-Continue with the above component training until strength improves, always following with full movement practice.

-Then as those components become easier, choose from components below as strength improves, randomly varying two to three exercises per session.

Bent Arm Crane Hold

Full Handstands

Bent Arm Low Tuck Hold

Handstand lower to feet on ground

Bent Arm High Tuck Hold

Bent Arm Straight Leg Hold

Handstand lower to Bent Arm Straight Leg Hold

-Finish with full movement.

Sets and repetitions are determined by your client’s ability to maintain safety and technique. In full skill movements, err on the side of lower reps and higher sets with adequate rest periods. In component movements, they can be performed as per normal strength and conditioning exercises.

Conclusion

As you can see, the use of research findings has to be tempered with real life experience and the necessities of providing a safe and productive training environment. Proper instruction requires a coach with an intimate knowledge of all the vagaries of the movement and techniques to be taught.

It’s currently in vogue to talk of evidence-based training, where research is said to lead the programming and performance of sessions. In response to this, there is now talk of evidence-informed instruction, wherein you make use of the research, but work with your experience and knowledge of your athletes to tweak and adjust as needed.

A good coach both knows the rules and knows when to break them.

One of the problems with coaching is the natural tendency to focus on the immediate changes in skill. This seems logical; if your athlete is performing the new skill well in the current session, then you must be doing something right! And maybe you are, but as we’ll show, you may be actually hindering their overall growth.

We can all agree that we are seeking the long-term retention of skill and increased performance for our athletes. Research tells us that there can be quite a difference between the performance within a training session and the retention of that performance over a period of time.

This is something that we see in the trenches as well. We’ve all known or had athletes that performed well in the gym and in training, but had less than stellar success in competition. Beyond psychosomatic issues, there may be some factors in the training itself that contribute to performance issues.

Let’s take a look at the major concepts of enhanced motor learning and how they may differ from standard coaching. We’ll also outline an example of real-life programming that takes advantages of best practice methods from research.

Schema

The following concepts are primarily derived from the research of Richard Schmidt (Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis) whose Schema Theory of motor learning was quite contrary to established theories and practice.

The theory states that we create generalized motor programs (GMP) for certain movement patterns we perform, and these programs are foundations for newly learned skills. The GMP contain parameters based on the sensory information from the body during the movement, the particular (muscle) actions generated to engage in the movement, and the sensory changes and outcome following those particular actions.

Essentially, it means that with every repetition of a movement skill, our bodies gather feedback to modify and improve the motor program. Each repetition and practice of a skill is a chance to improve. However, this doesn’t mean that we should be striving to achieve a “perfect” repetition in every training session.

What?! How does that make any kind of sense? Haven’t we all heard people say, “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect”? Well, it appears that they are wrong. In fact, the best methods of learning allow errors in practice, and it is the self-awareness of these errors and the subsequent changes that encourage the best progress. Let’s delve into why this is the case.

Feedback

A common coaching tactic is to provide immediate feedback after a mistake or break in technique by the athlete. “Elbows higher! Lift your chest up!” The results of which are easily seen; a good athlete listens to their coach and attempts to change their form and seemingly “gets better.”

And this is absolutely shown in research, when what is termed Knowledge of Results (KR), the feedback given immediately after (or even during) a skill, performance in that session is consistently better. And when KR is delayed, performance suffers. This seems logical; of course you’ll do better when you are observed and coached on correcting your errors as soon as you make them.

But, although short-term performance is better, when skills are measured in later sessions, it was the delayed KR group that had better retention of skill than those with immediate KR. Those people had better performance within practice, but ended up with a deterioration of performance below the delayed feedback group.

Why would this be so? The theory is that the coach’s immediate feedback interferes with the brain’s information processing of all the sensory and motor pattern reactions during and after the skill performance. The learning that would have happened was interrupted by the coaching.

In essence, immediate feedback is a crutch upon which the athlete becomes unknowingly dependent.

Bandwidth

Bandwidth refers to the error tolerance allowed the athlete in their skill training session. A narrow bandwidth means less tolerance before feedback is given to correct the issue. A wide bandwidth gives more leeway before telling the athlete to change technique.

Having less error tolerance allows for fewer mistakes in the practice session, and predictably leads to improved performance in the skill. It has to be that way because the coach isn’t allowing mistakes!

However, as shown in the feedback research, a narrow window of acceptable performance leads to poorer retention of skills versus a wider bandwidth, which allows more deviations from “perfect” technique.2

It’s thought that the too restrictive of a learning session deters the motor learning process.

Practice Arrangement

Blocked practice refers to the method of teaching wherein the same task is repeated before moving on to another drill; for example, shooting a basketball from the free throw line 50

times in a row, or hitting half a bucket of balls with your 9 iron before hitting the rest with your driver.

Random practice is just as it sounds, you have several tasks in your practice session and the sequencing is varied so that you aren’t performing the same drill again and again.

Just as with immediate feedback, it seems intuitively correct to practice one skill over and over to attain a mastery of the movement. And similarly, you will see an improved practice performance in the session. Yet again, when measured in the long term, random practice outperforms blocked practice.1

Here, it may be that the blocked practice is so repetitive and rote that the cognitive processing is diminished. It’s boring! So your brain takes a break even as your body keeps on trucking.

Attentional Focus

Attentional focus refers to what the athlete concentrates upon in the movement skill. An internal focus is directed to the movement itself or the positioning of the body in its performance. External focus has the learner more aware of the effects of the movement outside of the body.

Take the performance of a clean, for example. Internal focus of the skill relates to thinking about your back angle position in the first pull. In contrast, an external focus concentrates on the bar path and how high the pull should be before you move under the bar.

An external attentional focus has been correlated with improved performance both during the practice session and in long-term outcomes. An interesting study showed that giving a learner instruction on the optimal movement pattern prior to the performance of a skill lead to worse performances in the new movement than providing no instruction at all!

This would seem at odds with what’s said above regarding the importance of cognitive processing in motor learning. You’d think that an internal focus on the specifics of body mechanics and movement would help in the creation of a good motor pattern. It’s very counterintuitive that this isn’t the case.

But just as in immediate feedback, narrow bandwidth, and blocked practice methods; an internal focus interferes with learning because information is given too early in the process. In this case, the information is provided by the athlete themselves, and is separate from the information that would be gathered during the performance.

Whole vs Part Practice

Another common teaching method is drilling the athlete with parts of the whole movement pattern, as opposed to the entire skill itself. Again this seems to be a reasonable way of coaching, wherein a complex skill is broken down into more manageable sections, and those sections drilled until the achievement of a satisfactory performance.

One of the more extreme examples of this was when I was watching a friend’s mother taking a golf lesson. The instructor had divided the swing into what seemed to be a dozen different phases, and I’m not sure she was allowed to take a full swing during the entire hour!

Unfortunately, this has been shown to lessen motor learning as well. The separation of a skill into components (no matter how well reasoned) decreased overall performance as compared to practicing the full motor pattern. However, this effect may be ameliorated by using the “whole-part-whole” method , where the skill is practiced in its entirety, then in components, and then finally as a whole again all within the same session.

Real World Application

In our jobs of coaching, and in training ourselves, we should be concerned with performance in the long haul. Immediate improvements are meaningless if these skills are not retained and ably performed in subsequent practices and especially in competition.

Though the research all points towards delayed feedback, wide bandwidth, random practice, external attentional focus, and whole task practice; the realities of training an athlete necessitate a deviation from these ideal methods.

Safety is one of the primary concerns, especially in motor skills that involve implements or body movements that can be dangerous to the athlete. In these cases, the initial learning period should focus on safe performance.

Another concern, which is far from trivial, is the development of an athlete’s confidence. Delayed feedback may be best for long term learning, but if the frustration level rises too high, the practice session can degrade and the athlete will fail to benefit at all. An initial period of building confidence and reducing anxiety can help create quality practice. From there, the methods of allowing mistakes will best be put to use.

Also, it can be difficult to separate the learning of a skill of a particular movement from the actual need for strength of that skill, particularly in gymnastic type actions. In this case, using components as a teaching method is necessary to build the adequate amount of strength. Then moving to whole task learning as soon as possible.

The deliberate allowance of errors in form seems at odds with prevailing views, especially those such as Tommy Kono, with his insistence on Quality Training, where form and technique should be precise and as perfect as possible. However, looked upon from a different angle, they are actually the same approach. A quality performance has to start from somewhere and the errors made in the beginning lead to improved execution down the line. The athlete who is allowed to make an error in learning will become used to employing self-awareness much more quickly than those that are provided with the answers. These athletes have no need to look within when others are telling them exactly what to do.

General Sample Progression

First session

-Assessment of the athlete’s task performance.

-Identify possible dangerous form errors.

-Determine poor flexibility and/or strength deficits in task performance

-These form errors (dangerous, decreased flexibility/strength) will then addressed with specific “part task” practice drills.

-Determine if whole task training can be done safely.

-Engage in whole-part-whole sequencing with blocked practice.

-Feedback in this session can be regular but cue as much as possible on external focus.

Second session

-Repeat assessment of the movement skill.

-Blocked practice of component parts can still be done until strength and other deficit issues remain (especially if safety is still a concern).

-Whole-part-whole practice continues, but chosen part tasks are now randomized.

Third session and beyond

-Component practice tapers away and full skill practice is the emphasis with quality repetitions

-Wide bandwidth and significantly delayed feedback should be the norm, and feedback becomes more in the form of question/answer to encourage errors and the analysis of those errors.

Specific Sample Progression

The Bent Arm Tuck Press to Handstand

First Session

-Demonstrate full movement

-Observe client’s mimicking of the movement and identify:

-Dangerous form errors

-Weakness limitations

-Flexibility limitations

-Examples of dangerous form errors

-Too much of a jump forward can cause a fall onto the head or spine

-Elbows flared can cause undue shoulder strain and poor positioning

-Examples of weakness limitations

-Unable to maintain elbow angle or push up (weak triceps)

-Unable to maintain hips over shoulder position (weak trunk)

-Examples of flexibility limitations

-Wrist pain with weight-bearing (poor wrist extension flexibility)

-If no glaring limitations are seen, then:

-Teach full movement with cueing for:

-Eye gaze is directly at the floor

-Choose one or two internal cues during instruction

-Elbows in

-Shoulders in line with the fingers vertically

-Hips in line with shoulders vertically

-Full movements then taught as:

-Bent Arm Low Tuck, extend to Straight Leg and press to Handstand (with momentum)

.jpg)

-If flexibility limitations, then specific stretching prior to whole movement training.

-If weakness then teach one or two of the following components:

-Tripod hold

-Bent arm crane hold

.jpg)

-Bent arm tuck half press and drop legs

-After this part learning, end with full movement for a few repetitions.

Second Session

Full movement taught as:

-Bent Arm Low Tuck, extend to Straight Leg and press to Handstand (strict press)

Following up on weakness limitations, continue components above and remember to end with a few repetitions of the full movement.

Third Session and beyond

-Continue with the above component training until strength improves, always following with full movement practice.

-Then as those components become easier, choose from components below as strength improves, randomly varying two to three exercises per session.

Bent Arm Crane Hold

Full Handstands

Bent Arm Low Tuck Hold

Handstand lower to feet on ground

Bent Arm High Tuck Hold

Bent Arm Straight Leg Hold

Handstand lower to Bent Arm Straight Leg Hold

-Finish with full movement.

Sets and repetitions are determined by your client’s ability to maintain safety and technique. In full skill movements, err on the side of lower reps and higher sets with adequate rest periods. In component movements, they can be performed as per normal strength and conditioning exercises.

Conclusion

As you can see, the use of research findings has to be tempered with real life experience and the necessities of providing a safe and productive training environment. Proper instruction requires a coach with an intimate knowledge of all the vagaries of the movement and techniques to be taught.

It’s currently in vogue to talk of evidence-based training, where research is said to lead the programming and performance of sessions. In response to this, there is now talk of evidence-informed instruction, wherein you make use of the research, but work with your experience and knowledge of your athletes to tweak and adjust as needed.

A good coach both knows the rules and knows when to break them.

|

Jarlo Ilano, PT, MPT, OCS is a Physical Therapist (MPT, 1998) and board certified Orthopedic Clinical Specialist (OCS, 2011) with the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties. He is the Content Manager at Goldmedalbodies.com. Ryan is a co-founder of Gold Medal Bodies, producing gymnastic-style training programs in a detailed and accessible manner for the everyday trainee. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date