Bands: Time Under Tension and Rehabbing Injuries

Performing any sort of physical activity puts the participant at risk of injury. The risk continues to increase as the participant increases the intensity of their activity. After an injury, you will face the daunting task of rehabbing and getting yourself back to normal and back to whatever activities you participate in.

When a person injures themselves, they cause immense trauma to an area that requires a significant amount of time to recover. They may be forced to cease all activity for an extended period of time. During this time, they will experience muscular atrophy, or muscular waste, which is a shrinking of muscle mass and a loss of strength in the muscle itself. This can happen in as little as 72 hours and will get progressively worse the longer the muscle is not in use. Another big issue people face is that they injure themselves to the point where they require immobilization and lose range of motion through their joints.

The body becomes bigger and stronger through the process of hypertrophy. Hypertrophy is broken down into two distinct categories of myofibril and sarcoplasmic hypertrophy. Myofibril hypertrophy occurs due to overload stimulus (lifting heavy loads), which applies trauma to individual muscle fibers. The body treats this as an injury and overcompensates during recovery by increasing the volume and density of myofibrils (the contractile parts of a muscle), so injury does not occur again. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy occurs when you deplete the sarcoplasm (energy source surrounding myofibrils) in training, and the body repeats the same process through recovery. When rehabbing any injury, you will look to achieve both kinds of hypertrophy to combat atrophy and recover your lost muscle mass and to make yourself stronger so you will not get injured again.

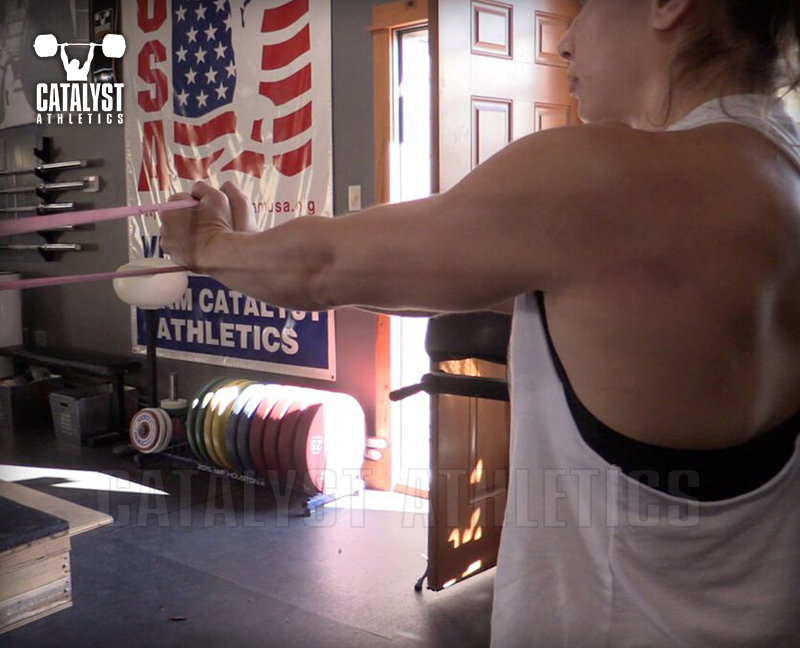

One of the most undervalued pieces of gym equipment are bands. Bands are any elastic material that constantly resist motion once they are stretched past their initial length. The resistance of bands can range from under 3 pounds to over 50 pounds or more depending on the thickness and length to which you stretch them. They can be substituted for any exercise requiring weights or added to any movement to increase the difficulty of the movement. They are especially beneficial when working on exercises with joints that have a large range of motion and for exercises that occur through multiple planes of movement. A few examples of these could be banded lateral and frontal raises or banded lateral lunges.

The best way to achieve muscular hypertrophy is focusing on time under tension. Time under tension refers to the total time the muscle is under resistance during an exercise. For the purpose of this article, this can be seen as any time the band has lost slack and is now resisting movement. While rehabbing an injury, and thus training for strength and size, the desired time under tension falls anywhere between 40 and 60 seconds per set. Anything under this time the muscle will not have depleted its stores of energy in the sarcoplasm. On the other hand, anything longer than this can lead to overtraining where the myofibrils are stressed too much, and you can become re-injured.

After you are cleared to begin rehabbing your injury, the first thing you must accomplish is getting back any range of motion that you lost due to immobilization. Bands will play a crucial role in restoring the range of motion because they can be utilized in athletes that resist a therapist from performing passive range of motion. Passive range of motion is the amount of motion through an athlete’s joints that the therapist can achieve when they are relaxed. Passive range of motion includes any sort of assisted stretching where the athlete is not the one controlling the stretch. These include assisted hamstring stretches, assisted hip and groin stretches, and assisted external rotation and abduction of the shoulder. However, many people will stiffen up and stop the joint from being moved, thus decreasing the effectiveness of passive range of motion. Resistance bands can help with this by promoting reciprocal inhibition. Reciprocal inhibition is the direct response to muscle contractions around a joint. Muscles around joints move in synchrony with each other to move the joint. While one muscle is being contracted and worked, the other is forced to relax. In restoring range of motion, this is helpful by performing banded exercises in the opposite direction of the desired range of motion to fatigue the muscles guarding the joint. Thus, the athlete will be able to increase his motion and allow the therapist to perform passive range of motion. Used in tandem, the bands will allow the athlete to tire the muscles keeping the joint capsule from returning to its original range of motion and will allow a therapist or the athlete themselves to get a deeper stretch than they could before.

After an athlete regains some range of motion, they will want to begin strengthening the beginning ends of movement. The resistance bands will allow you to strengthen your injury site while modulating the amount of tension and force experienced by how far you stretch the band. This will be beneficial to you, as bands will allow you to put your extremities in positions that allow for strengthening while still allowing the band to stress and stretch the desired tissues. The first kinds of activities you will want to use when rehabbing your injury are isometric contractions. Isometric contractions are exercises where the muscle or muscle group is activated, but the individual muscle fibers are held at a constant length. These sorts of exercises would include external and internal shoulder rotation walkouts, where the athlete holds the arm in the predetermined position and walks away from the band, thus increasing the tension but keeping the muscle fibers at a constant length. When performing isometric exercises, little to no joint motion will take place. These sorts of exercises will be preferable after an injury because movement may disrupt scar tissue or re-aggravate your injury. Also, movement through the joint's full range of motion may be painful or impossible due to inflammation or atrophy. However, by using isometric exercises, you will be able to safely contract your muscles and gain the time under tension necessary to begin the process of hypertrophy. Furthermore, you will be able to strengthen specific muscles that will be used to stabilize the joint capsule for larger movements later on in rehab.

After sufficient time has been spent focusing on acquiring the desired range of motion and the joint has been stabilized, it is time to move past isometric exercises. While isometric exercises are amazingly beneficial at the beginning of rehab, after a few weeks, their effectiveness drops significantly, and you will need to focus on isotonic contraction exercises. Isotonic contractions are exercises that force the joint through its full range of motion while under constant resistance. An example of these could be internal and external shoulder rotations. The difference between these exercises and the previous example is that instead of holding the arm in a predetermined position the athlete will force the arm through the range of motion. This will increase the tension the athlete feels towards the top of the motion and force the joint through different planes of motion. The category of isotonic contractions is further broken down into concentric and eccentric contractions. Concentric contractions activate the muscle and allow it to shorten, for example, pulling the dumbbell up on a curl. Eccentric contractions force the muscle to lengthen due to an external load, for example, the lowering of the dumbbell in a curl. While both are important in achieving the desired time under tension and hypertrophy, eccentric contractions are much more valuable in the rehab process. Going back to the example of the internal shoulder rotations the concentric portion of the movement is when the arm is being brought to the body, while the eccentric portion of the movement is as the arm is moving back to its starting position. When rehabbing a shoulder injury, it is beneficial to not only use this movement, but also to focus on a slow and controlled eccentric contraction. This is because the body is stronger in eccentric contractions than it is with concentric contraction and because of this, the body becomes stronger and more stable in a shorter amount of time.

You may be asking yourself, “If that’s all there is to it, why should I use bands and not just go back to weights?” The problem is that weights do not stress the eccentric phase of muscle contractions. The majority of weight training is done by pulling weights closer to the body and thus training concentric contraction. However, with bands, the athlete is forced to focus on eccentric control because the band never loses tension. This helps the rehab process in a multitude of ways. Since eccentric exercises allow us to get stronger faster, they significantly cut down the amount of time spent rehabbing. Also, eccentric contractions are more important in controlling and resisting movement which helps to stabilize joints post-injury. As stated by physical therapist Zachary Polk in his work with athletes, "What I find useful with the performance of strengthening while using bands is the amount of emphasis that you can place on eccentric control and the capability to change exercises easily to achieve the desired treatment effect. In other words, you can either move the band or the patient in a way to ensure a more specific line of pull that corresponds to the desired muscle to be strengthened.” Finally, focusing on eccentric contractions with bands allows you to double your amount of time under tension allowing you achieve hypertrophy in a shorter period of time.

Once an athlete has fully achieved the desired range of motion and has strengthened the muscles supporting the joint capsule and the tissues within the joint capsule, they can begin to return to normal activity. The initial workouts following a release from rehab should be cautious and calculated to prevent reinjuring or re-aggravating the area.

When transitioning into a gym setting, one should focus on using some form of banded warm-up before beginning their weight training. This will help your stabilizing muscles fire correctly to keep your joints stable throughout training. It will also help to strengthen these stabilizing muscles that can sometimes be forgotten when weight training. Furthermore, the warm-up will act as pre-hab to help prevent injuries before they happen.

The shoulder is the joint that possesses the most range of motion and thus is constantly at risk for injury. When stabilizing the shoulder, four muscles (the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis) work to keep the shoulder joint in place. All of these muscles are not normally trained when lifting shoulders, but their importance cannot be forgotten. The following exercises can be used before every upper-body lifting day to warm up the back and shoulders and as prehab to prevent any shoulder injury from occurring. Perform the following exercises using a band that you can control through 15 repetitions while focusing on the eccentric portion of the movement with a 3 second pause at the top of the movement: Row, Reverse Fly, Pulldown, 90-90, Scaption (raising arms up at 45-degree angle) and Flexion (raising arms straight up).

Bands are one of the most underappreciated pieces of gym equipment readily available in almost every gym setting. They can be utilized as a warm-up, prehab, rehab, or even to increase the effectiveness of a lift. Incorporating bands into your workouts will allow you to smash through plateaus, prevent injuries from occurring and allow you to get back faster and stronger from an injury. Next time you go into the gym, make a concerted effort to incorporate them into some phase of your workout or add them into your rehab process to cut down on your recovery time to get you back to lifting sooner than you ever thought possible.

When a person injures themselves, they cause immense trauma to an area that requires a significant amount of time to recover. They may be forced to cease all activity for an extended period of time. During this time, they will experience muscular atrophy, or muscular waste, which is a shrinking of muscle mass and a loss of strength in the muscle itself. This can happen in as little as 72 hours and will get progressively worse the longer the muscle is not in use. Another big issue people face is that they injure themselves to the point where they require immobilization and lose range of motion through their joints.

The body becomes bigger and stronger through the process of hypertrophy. Hypertrophy is broken down into two distinct categories of myofibril and sarcoplasmic hypertrophy. Myofibril hypertrophy occurs due to overload stimulus (lifting heavy loads), which applies trauma to individual muscle fibers. The body treats this as an injury and overcompensates during recovery by increasing the volume and density of myofibrils (the contractile parts of a muscle), so injury does not occur again. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy occurs when you deplete the sarcoplasm (energy source surrounding myofibrils) in training, and the body repeats the same process through recovery. When rehabbing any injury, you will look to achieve both kinds of hypertrophy to combat atrophy and recover your lost muscle mass and to make yourself stronger so you will not get injured again.

One of the most undervalued pieces of gym equipment are bands. Bands are any elastic material that constantly resist motion once they are stretched past their initial length. The resistance of bands can range from under 3 pounds to over 50 pounds or more depending on the thickness and length to which you stretch them. They can be substituted for any exercise requiring weights or added to any movement to increase the difficulty of the movement. They are especially beneficial when working on exercises with joints that have a large range of motion and for exercises that occur through multiple planes of movement. A few examples of these could be banded lateral and frontal raises or banded lateral lunges.

The best way to achieve muscular hypertrophy is focusing on time under tension. Time under tension refers to the total time the muscle is under resistance during an exercise. For the purpose of this article, this can be seen as any time the band has lost slack and is now resisting movement. While rehabbing an injury, and thus training for strength and size, the desired time under tension falls anywhere between 40 and 60 seconds per set. Anything under this time the muscle will not have depleted its stores of energy in the sarcoplasm. On the other hand, anything longer than this can lead to overtraining where the myofibrils are stressed too much, and you can become re-injured.

After you are cleared to begin rehabbing your injury, the first thing you must accomplish is getting back any range of motion that you lost due to immobilization. Bands will play a crucial role in restoring the range of motion because they can be utilized in athletes that resist a therapist from performing passive range of motion. Passive range of motion is the amount of motion through an athlete’s joints that the therapist can achieve when they are relaxed. Passive range of motion includes any sort of assisted stretching where the athlete is not the one controlling the stretch. These include assisted hamstring stretches, assisted hip and groin stretches, and assisted external rotation and abduction of the shoulder. However, many people will stiffen up and stop the joint from being moved, thus decreasing the effectiveness of passive range of motion. Resistance bands can help with this by promoting reciprocal inhibition. Reciprocal inhibition is the direct response to muscle contractions around a joint. Muscles around joints move in synchrony with each other to move the joint. While one muscle is being contracted and worked, the other is forced to relax. In restoring range of motion, this is helpful by performing banded exercises in the opposite direction of the desired range of motion to fatigue the muscles guarding the joint. Thus, the athlete will be able to increase his motion and allow the therapist to perform passive range of motion. Used in tandem, the bands will allow the athlete to tire the muscles keeping the joint capsule from returning to its original range of motion and will allow a therapist or the athlete themselves to get a deeper stretch than they could before.

After an athlete regains some range of motion, they will want to begin strengthening the beginning ends of movement. The resistance bands will allow you to strengthen your injury site while modulating the amount of tension and force experienced by how far you stretch the band. This will be beneficial to you, as bands will allow you to put your extremities in positions that allow for strengthening while still allowing the band to stress and stretch the desired tissues. The first kinds of activities you will want to use when rehabbing your injury are isometric contractions. Isometric contractions are exercises where the muscle or muscle group is activated, but the individual muscle fibers are held at a constant length. These sorts of exercises would include external and internal shoulder rotation walkouts, where the athlete holds the arm in the predetermined position and walks away from the band, thus increasing the tension but keeping the muscle fibers at a constant length. When performing isometric exercises, little to no joint motion will take place. These sorts of exercises will be preferable after an injury because movement may disrupt scar tissue or re-aggravate your injury. Also, movement through the joint's full range of motion may be painful or impossible due to inflammation or atrophy. However, by using isometric exercises, you will be able to safely contract your muscles and gain the time under tension necessary to begin the process of hypertrophy. Furthermore, you will be able to strengthen specific muscles that will be used to stabilize the joint capsule for larger movements later on in rehab.

After sufficient time has been spent focusing on acquiring the desired range of motion and the joint has been stabilized, it is time to move past isometric exercises. While isometric exercises are amazingly beneficial at the beginning of rehab, after a few weeks, their effectiveness drops significantly, and you will need to focus on isotonic contraction exercises. Isotonic contractions are exercises that force the joint through its full range of motion while under constant resistance. An example of these could be internal and external shoulder rotations. The difference between these exercises and the previous example is that instead of holding the arm in a predetermined position the athlete will force the arm through the range of motion. This will increase the tension the athlete feels towards the top of the motion and force the joint through different planes of motion. The category of isotonic contractions is further broken down into concentric and eccentric contractions. Concentric contractions activate the muscle and allow it to shorten, for example, pulling the dumbbell up on a curl. Eccentric contractions force the muscle to lengthen due to an external load, for example, the lowering of the dumbbell in a curl. While both are important in achieving the desired time under tension and hypertrophy, eccentric contractions are much more valuable in the rehab process. Going back to the example of the internal shoulder rotations the concentric portion of the movement is when the arm is being brought to the body, while the eccentric portion of the movement is as the arm is moving back to its starting position. When rehabbing a shoulder injury, it is beneficial to not only use this movement, but also to focus on a slow and controlled eccentric contraction. This is because the body is stronger in eccentric contractions than it is with concentric contraction and because of this, the body becomes stronger and more stable in a shorter amount of time.

You may be asking yourself, “If that’s all there is to it, why should I use bands and not just go back to weights?” The problem is that weights do not stress the eccentric phase of muscle contractions. The majority of weight training is done by pulling weights closer to the body and thus training concentric contraction. However, with bands, the athlete is forced to focus on eccentric control because the band never loses tension. This helps the rehab process in a multitude of ways. Since eccentric exercises allow us to get stronger faster, they significantly cut down the amount of time spent rehabbing. Also, eccentric contractions are more important in controlling and resisting movement which helps to stabilize joints post-injury. As stated by physical therapist Zachary Polk in his work with athletes, "What I find useful with the performance of strengthening while using bands is the amount of emphasis that you can place on eccentric control and the capability to change exercises easily to achieve the desired treatment effect. In other words, you can either move the band or the patient in a way to ensure a more specific line of pull that corresponds to the desired muscle to be strengthened.” Finally, focusing on eccentric contractions with bands allows you to double your amount of time under tension allowing you achieve hypertrophy in a shorter period of time.

Once an athlete has fully achieved the desired range of motion and has strengthened the muscles supporting the joint capsule and the tissues within the joint capsule, they can begin to return to normal activity. The initial workouts following a release from rehab should be cautious and calculated to prevent reinjuring or re-aggravating the area.

When transitioning into a gym setting, one should focus on using some form of banded warm-up before beginning their weight training. This will help your stabilizing muscles fire correctly to keep your joints stable throughout training. It will also help to strengthen these stabilizing muscles that can sometimes be forgotten when weight training. Furthermore, the warm-up will act as pre-hab to help prevent injuries before they happen.

The shoulder is the joint that possesses the most range of motion and thus is constantly at risk for injury. When stabilizing the shoulder, four muscles (the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis) work to keep the shoulder joint in place. All of these muscles are not normally trained when lifting shoulders, but their importance cannot be forgotten. The following exercises can be used before every upper-body lifting day to warm up the back and shoulders and as prehab to prevent any shoulder injury from occurring. Perform the following exercises using a band that you can control through 15 repetitions while focusing on the eccentric portion of the movement with a 3 second pause at the top of the movement: Row, Reverse Fly, Pulldown, 90-90, Scaption (raising arms up at 45-degree angle) and Flexion (raising arms straight up).

Bands are one of the most underappreciated pieces of gym equipment readily available in almost every gym setting. They can be utilized as a warm-up, prehab, rehab, or even to increase the effectiveness of a lift. Incorporating bands into your workouts will allow you to smash through plateaus, prevent injuries from occurring and allow you to get back faster and stronger from an injury. Next time you go into the gym, make a concerted effort to incorporate them into some phase of your workout or add them into your rehab process to cut down on your recovery time to get you back to lifting sooner than you ever thought possible.

|

Alex Card is a former junior college baseball player and current student at Baylor University. Besides baseball, he has always had a passion for weightlifting and learning how the body works. He is from Nashville, Tennessee. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date