Utilizing Post Activation Potentiation to Maximize Power Output

How many of us early in our training history looked at the warm-up as just some time for a little stretching, coupled with a little cardio before hitting the squat rack? Not anymore. Static stretching before a training session has gone the way of the pay phone. Today, coaches incorporate dynamic exercises to increase heart rate and core body temperature while taking the body through motions similar to the ones used in training to establish proper neuro-muscular firing patterns and increase muscle efficiency. One warm-up technique discussed in the literature these days is using high muscle loading exercises prior to training to hyper-stimulate the Central Nervous System (CNS) and elicit post activation potentiation responses or PAP.

Positive response to stress

PAP is a phenomenon generated from maximal or near maximal lifts that increase neural pathway activity resulting in acute improvements in muscle force production and the rate of force development. Lee Brown Ed.D. CSCS, Professor of Strength and Conditioning at Cal State Fullerton, explained it to me this way: “PAP is a subsequent increase in muscle force production during an explosive movement like a vertical jump following a heavy resistance exercise.” This is the result of two mechanisms. First, just like the sound of a whistle draws athletes to their coach, a high intensity load and the associated contraction draws the attention of an athlete’s nervous system to the task on hand. Realizing additional high intensity loads are coming, the CNS increases neural activity maximizing musculoskeletal responses to a stimulus. Second, the contractile filaments in muscle, actin and myosin, show an increased sensitivity to calcium enhancing cross-bridge formation and force production.

One of the most compelling stories regarding the use of PAP is from Gullich and Schmidtbliecher, who reported in 1995 about a bob sledding team that used pre-competition warm ups to elicit PAPs, and went on to win a world championship. Unfortunately, this is a report, not a research study. Furthermore, bob sledding is a multi-faceted sport with numerous variables that can effect run times, like error-free entry into the sled, track conditions and driver performance. Did eliciting PAPs give these athletes a competitive edge? We’ll never know, but it is an interesting story and does make one wonder.

Determining the effectiveness of PAP

Jacob Wilson Ph.D., CSCS, Assistant Professor in Health Sciences and Human Performance at the University of Tampa said, “pre-conditioning activities can augment power production capacity in several motor skills (i.e., sprinting, jumping and throwing).” However, “you need to use an exercise that’s specific to the muscles you want to work”, says Brown. If you want to enhance jumping, pick an exercise that uses the hip flexors, quads, hamstrings and gastrocnemius while to enhance throwing choose an exercise that works the back, chest and arms.

The majority of studies I reviewed used either back squats or bench press to elicit a PAP and then recorded changes in sprinting speed, vertical jump or medicine ball throws. However, Brown agreed that as long as you chose the appropriate exercise, you could see improvements in power based movements like the clean and jerk or snatch. .

Wilson and his colleagues at the University of Tampa recently performed a meta-analysis of 32 studies in the literature on PAP. After analyzing the data, they came up with the following recommendations for “inexperienced individuals select a moderate intensity conditioning activity [60-85% of 1 Repetition Maximum and only perform one set.” Although advanced and highly experienced athletes can tolerate two to three sets at 60-85percent of their 1RM, Brown believes that “there’s no reason to do no more than one set.”

A couple of studies that weren’t included in Wilson’s review were those that employed isometric contractions to elicit PAP. Joseph Berning, Ph.D., CSCS and associates reported that using a functional isometric squat at 150 percent of 1RM improved counter movement vertical jump in trained individuals while Joseph Esformes, PhD, CSCS and his colleagues at Cardiff Metropolitan University utilized a maximal isometric bench press exercise at 110o degrees of elbow flexion to enhance upper body power output in competitive rugby players.

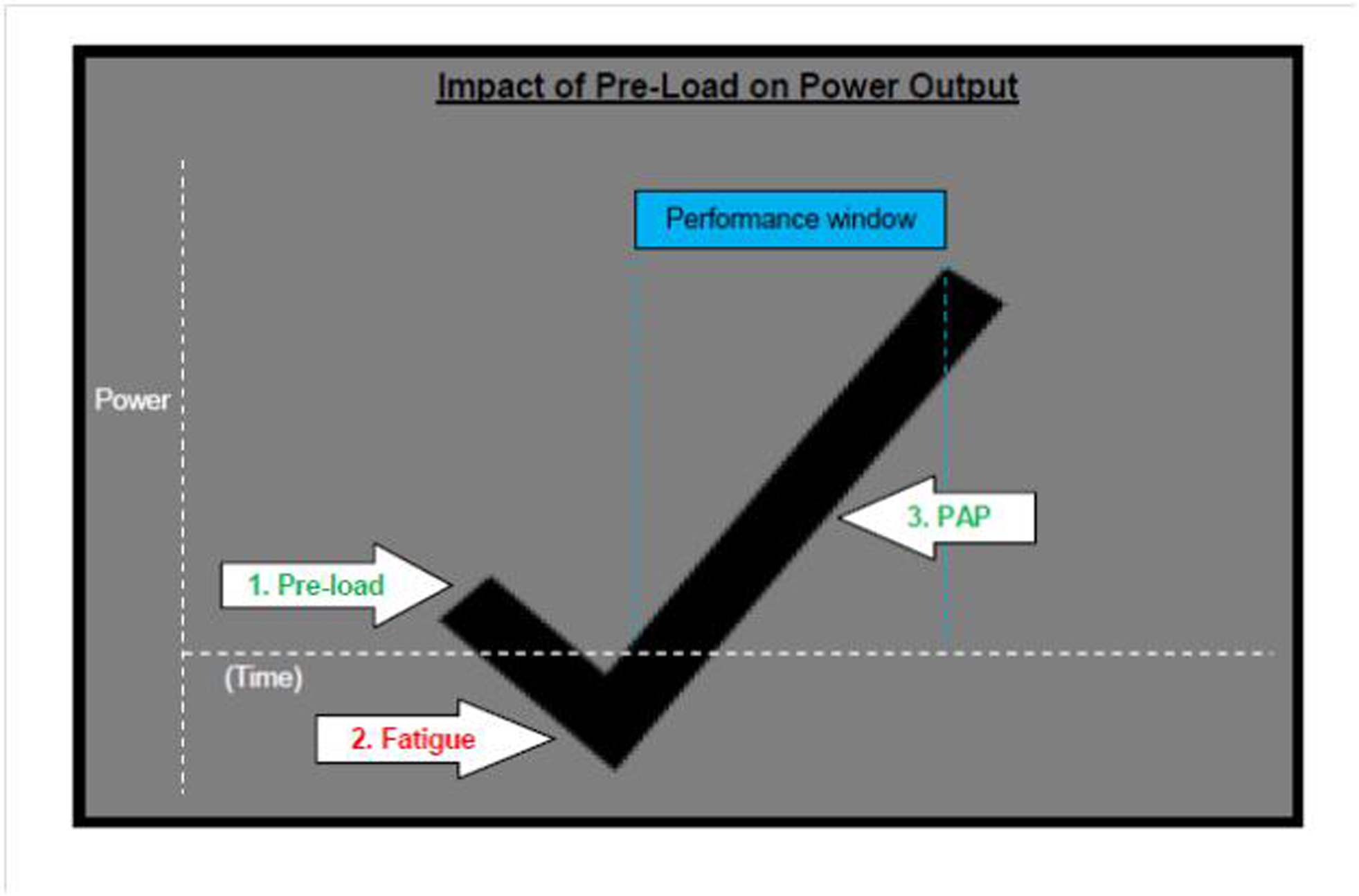

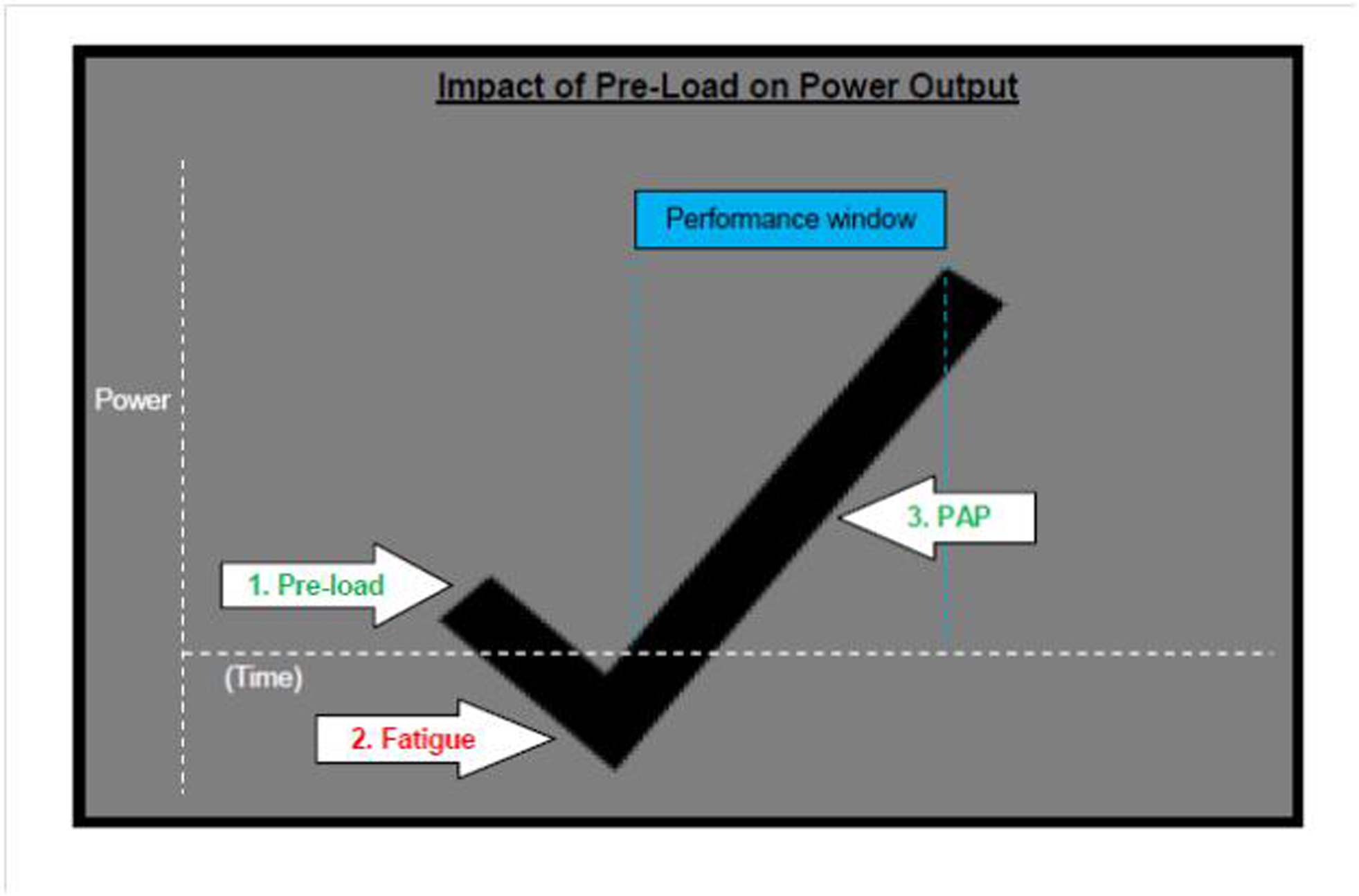

So, we know eliciting PAP can increase power output by two to 10 percent in some individuals. However, there isn’t a consensus on what the best stimulus is to elicit it, so you have to experiment. No matter what exercise, load or volume you decide on there are some critical components that can’t be avoided. First, rest periods of seven to 10 minutes after the pre-load exercise result in the best outputs. Unfortunately, I’m not talking about active rest where your athlete works on their technique or spots another team member but just sitting and resting. One explanation that really helped me visualize the process was when Brown said, “view eliciting PAP like a checkmark”, because ''the athlete has to overcome the fatigue of the pre-load.” So as you can see in the figure below, no matter what type of athlete you’re working with, immediately post pre-load power output diminishes but then over time thanks to increased neural activity and changes in muscle fiber sensitivity, power output increases.

The second factor to take into consideration is variability between athletes. You can have three highly conditioned athletes of equal strength and power that perform the same pre-load exercise but unfortunately, one’s performance window might be 12 minutes, another’s seven minutes and the third might not potentiate at all. Also, in the figure above it appears as PAP goes on forever but “the ability to potentiate performance likely dissipates by 30 minutes after a conditioning activity,” says Wilson. Because of this, I recommend attempting to elicit PAP during your assessment days. If you’re successful, then you can work it into an athlete’s conditioning and competition warm-ups. However, keep in mind PAP does not increase strength but power. The best time to add it is during the power phase of a training cycle.

Working PAP into Training

Example 1: An athlete has good upper extremity power but during the snatch sometimes fails in the scoop. Using a lift that elicits PAP in the lower body might help. So at your next assessment day, you employ the following:

1. Normal Training Warm-UP: I’m sure you all have a routine for your athletes. However if you’re looking for some new ideas, I highly recommend Greg Everett’s article in the November 2011 edition entitled, “Our Warm-up is a Warm-UP”.

2. Short Rest Period: (4-5 minutes) This could consist of foam rolling, some light static stretching or some quiet time to mentally prepare. I emphasize light because overstretching can reduce power output and performance.

3. PAP Eliciting Warm-UP: Perform 1 set of 5 repetitions of a back squat at 90% of 1 RM.

4. Rest Period: (7-10 minutes)

5. Testing

6. Normal Prescribed Cool-Down

Example 2: Athlete has good lower body power but fails in a clean and jerk driving the barbell overhead. Follow the same plan as you did before except substitute an upper body exercise to elicit PAP.

3. PAP Eliciting Warm-UP: Before beginning this exercise, make sure the power rack is securely bolted to the floor. Next, the athlete performs 1 repetition of a maximal isometric flat bench press holding the lift for seven seconds. Instruct the athlete to push the bar upwards into the rack cross bars as fast and as forcefully as they can and be sure to count the time out loud to motivate the athlete.

Challenging to Employ

Working this tool into your training cycles is definitely challenging, but one reason I think Olympic lifting lends itself to this tool is proximity. You have all the equipment you need to elicit PAP in your athletes at training sessions and competitions versus a coach whose athletes practice and compete on a track or playing field. Give it try. If your athlete responds, you’re looking at an immediate change in power output of two to 10 percent. It might be the difference between standing on the podium or standing in the crowd.

References

1. Phone Interview 5/14/14with Lee Brown, EdD, CSCS*D, FNSCA, FACSM, Professor, Strength and Conditioning, California State University, Fullerton, e-mail:leebrown@fullerton.edu

2. Lorenz, D. Postactivation potentiation an introduction. Int J Sports Phys Ther 6(3): 234-240,2011.

3. Robbins, DW. Postactivation potentiation and its practical applicability: A brief review. J Strength Cond Res 19(2) 453-457, 2005.

4. Sale, D. Postactivation potentiation: Role in human performance. Exercise and Sport Science Reviews 30(3): 138-143, 2002.

5. Wilson JM, Duncan NM, et.al. Meta-analysis of postactivation potentiation and power: effects of conditioning activity, volume, gender, rest periods, and training status. J Strength Cond Res 27(3): 854-859, 2013.

6. Berning JM, Adams KJ, et.al. Effect of functional isometric squats on vertical jump in trained and untrained men. J Strength Cond Res 24(9): 2285-2289, 2010.

7. Esformes, JI, Keenan, M, Moody, J, and Bampouras, TM. Effect of different types of conditioning contraction on upper body postactivation potentiation. J Strength Cond Res 25(1): 143–148, 2011.

Positive response to stress

PAP is a phenomenon generated from maximal or near maximal lifts that increase neural pathway activity resulting in acute improvements in muscle force production and the rate of force development. Lee Brown Ed.D. CSCS, Professor of Strength and Conditioning at Cal State Fullerton, explained it to me this way: “PAP is a subsequent increase in muscle force production during an explosive movement like a vertical jump following a heavy resistance exercise.” This is the result of two mechanisms. First, just like the sound of a whistle draws athletes to their coach, a high intensity load and the associated contraction draws the attention of an athlete’s nervous system to the task on hand. Realizing additional high intensity loads are coming, the CNS increases neural activity maximizing musculoskeletal responses to a stimulus. Second, the contractile filaments in muscle, actin and myosin, show an increased sensitivity to calcium enhancing cross-bridge formation and force production.

One of the most compelling stories regarding the use of PAP is from Gullich and Schmidtbliecher, who reported in 1995 about a bob sledding team that used pre-competition warm ups to elicit PAPs, and went on to win a world championship. Unfortunately, this is a report, not a research study. Furthermore, bob sledding is a multi-faceted sport with numerous variables that can effect run times, like error-free entry into the sled, track conditions and driver performance. Did eliciting PAPs give these athletes a competitive edge? We’ll never know, but it is an interesting story and does make one wonder.

Determining the effectiveness of PAP

Jacob Wilson Ph.D., CSCS, Assistant Professor in Health Sciences and Human Performance at the University of Tampa said, “pre-conditioning activities can augment power production capacity in several motor skills (i.e., sprinting, jumping and throwing).” However, “you need to use an exercise that’s specific to the muscles you want to work”, says Brown. If you want to enhance jumping, pick an exercise that uses the hip flexors, quads, hamstrings and gastrocnemius while to enhance throwing choose an exercise that works the back, chest and arms.

The majority of studies I reviewed used either back squats or bench press to elicit a PAP and then recorded changes in sprinting speed, vertical jump or medicine ball throws. However, Brown agreed that as long as you chose the appropriate exercise, you could see improvements in power based movements like the clean and jerk or snatch. .

Wilson and his colleagues at the University of Tampa recently performed a meta-analysis of 32 studies in the literature on PAP. After analyzing the data, they came up with the following recommendations for “inexperienced individuals select a moderate intensity conditioning activity [60-85% of 1 Repetition Maximum and only perform one set.” Although advanced and highly experienced athletes can tolerate two to three sets at 60-85percent of their 1RM, Brown believes that “there’s no reason to do no more than one set.”

A couple of studies that weren’t included in Wilson’s review were those that employed isometric contractions to elicit PAP. Joseph Berning, Ph.D., CSCS and associates reported that using a functional isometric squat at 150 percent of 1RM improved counter movement vertical jump in trained individuals while Joseph Esformes, PhD, CSCS and his colleagues at Cardiff Metropolitan University utilized a maximal isometric bench press exercise at 110o degrees of elbow flexion to enhance upper body power output in competitive rugby players.

So, we know eliciting PAP can increase power output by two to 10 percent in some individuals. However, there isn’t a consensus on what the best stimulus is to elicit it, so you have to experiment. No matter what exercise, load or volume you decide on there are some critical components that can’t be avoided. First, rest periods of seven to 10 minutes after the pre-load exercise result in the best outputs. Unfortunately, I’m not talking about active rest where your athlete works on their technique or spots another team member but just sitting and resting. One explanation that really helped me visualize the process was when Brown said, “view eliciting PAP like a checkmark”, because ''the athlete has to overcome the fatigue of the pre-load.” So as you can see in the figure below, no matter what type of athlete you’re working with, immediately post pre-load power output diminishes but then over time thanks to increased neural activity and changes in muscle fiber sensitivity, power output increases.

The second factor to take into consideration is variability between athletes. You can have three highly conditioned athletes of equal strength and power that perform the same pre-load exercise but unfortunately, one’s performance window might be 12 minutes, another’s seven minutes and the third might not potentiate at all. Also, in the figure above it appears as PAP goes on forever but “the ability to potentiate performance likely dissipates by 30 minutes after a conditioning activity,” says Wilson. Because of this, I recommend attempting to elicit PAP during your assessment days. If you’re successful, then you can work it into an athlete’s conditioning and competition warm-ups. However, keep in mind PAP does not increase strength but power. The best time to add it is during the power phase of a training cycle.

Working PAP into Training

Example 1: An athlete has good upper extremity power but during the snatch sometimes fails in the scoop. Using a lift that elicits PAP in the lower body might help. So at your next assessment day, you employ the following:

1. Normal Training Warm-UP: I’m sure you all have a routine for your athletes. However if you’re looking for some new ideas, I highly recommend Greg Everett’s article in the November 2011 edition entitled, “Our Warm-up is a Warm-UP”.

2. Short Rest Period: (4-5 minutes) This could consist of foam rolling, some light static stretching or some quiet time to mentally prepare. I emphasize light because overstretching can reduce power output and performance.

3. PAP Eliciting Warm-UP: Perform 1 set of 5 repetitions of a back squat at 90% of 1 RM.

4. Rest Period: (7-10 minutes)

5. Testing

6. Normal Prescribed Cool-Down

Example 2: Athlete has good lower body power but fails in a clean and jerk driving the barbell overhead. Follow the same plan as you did before except substitute an upper body exercise to elicit PAP.

3. PAP Eliciting Warm-UP: Before beginning this exercise, make sure the power rack is securely bolted to the floor. Next, the athlete performs 1 repetition of a maximal isometric flat bench press holding the lift for seven seconds. Instruct the athlete to push the bar upwards into the rack cross bars as fast and as forcefully as they can and be sure to count the time out loud to motivate the athlete.

Challenging to Employ

Working this tool into your training cycles is definitely challenging, but one reason I think Olympic lifting lends itself to this tool is proximity. You have all the equipment you need to elicit PAP in your athletes at training sessions and competitions versus a coach whose athletes practice and compete on a track or playing field. Give it try. If your athlete responds, you’re looking at an immediate change in power output of two to 10 percent. It might be the difference between standing on the podium or standing in the crowd.

References

1. Phone Interview 5/14/14with Lee Brown, EdD, CSCS*D, FNSCA, FACSM, Professor, Strength and Conditioning, California State University, Fullerton, e-mail:leebrown@fullerton.edu

2. Lorenz, D. Postactivation potentiation an introduction. Int J Sports Phys Ther 6(3): 234-240,2011.

3. Robbins, DW. Postactivation potentiation and its practical applicability: A brief review. J Strength Cond Res 19(2) 453-457, 2005.

4. Sale, D. Postactivation potentiation: Role in human performance. Exercise and Sport Science Reviews 30(3): 138-143, 2002.

5. Wilson JM, Duncan NM, et.al. Meta-analysis of postactivation potentiation and power: effects of conditioning activity, volume, gender, rest periods, and training status. J Strength Cond Res 27(3): 854-859, 2013.

6. Berning JM, Adams KJ, et.al. Effect of functional isometric squats on vertical jump in trained and untrained men. J Strength Cond Res 24(9): 2285-2289, 2010.

7. Esformes, JI, Keenan, M, Moody, J, and Bampouras, TM. Effect of different types of conditioning contraction on upper body postactivation potentiation. J Strength Cond Res 25(1): 143–148, 2011.

|

Mark Kaelin, M.S., CSCS is a certified strength and conditioning specialist with the National Strength and Conditioning Association and has almost 20 years of experience working in health and fitness. He is currently an instructor in the biology department at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Ky., and writes frequently for health and fitness publications. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date