Kyphosis

Working as a generalist strength & conditioning coach using CrossFit methodology appears to be a case of “Jack Of All Trades, Master Of None” and in some sense this may be accurate. I teach some gymnastics, but I am not a gymnastics coach and will never develop an athlete to even an “A” level gymnast. We play with the Olympic lifts and although I am a “USAW Club Coach” my list of ’08 hopefuls is…um, skinny. For most endeavors I feel that I am adequate for the job but for some people this lack of specialization may be a bit buggaring.

I enjoy the challenge and the freedom this work affords me and I DO feel that I have attained a high level of understanding in one element of the generalist coaching: An eye for Good Movement. I’ve seen quite a number of cyclists, soccer players, stay-at-home-moms (both professional and amateur), ruggers…and from this experience I can spot “good movement” pretty quickly. Does someone have adequate hip and shoulder flexibility? Watch them overhead squat, even with just a broomstick, and you will know instantly. Shoulder mobility, flexibility and health are actually something I have zeroed in on lately as I have seen problems across all movement backgrounds, ages and in both genders. This has actually been surprising as folks can range from sedentary to athletic, obese to lean and they frequently have severe limitations in shoulder strength and mobility. These limitations not only impede progress in the gym but also frequently predispose the individual to further problems such as rotator cuff impingement and deteriorating posture. I’ve been tinkering with ways to address this problem but before we look at that let’s look at what is going on with the shoulder girdle itself.

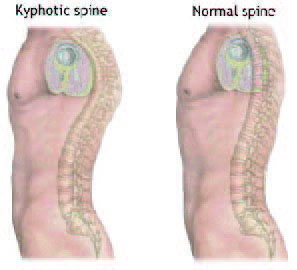

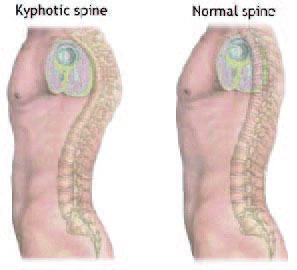

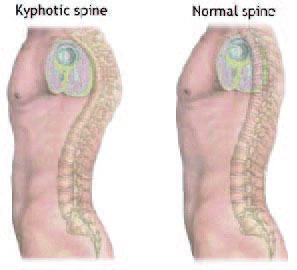

Kyphosis

In a normal spine we have a structurally sound curve in the low back, with a counter curve in the thoracic region, and a final counter curve in the cervical region. From an engineering perspective arches such as those found in the human spine are remarkably strong and are capable of bearing tremendous loads. Perturbing the structure of the arch however causes the integrity to plummet, thus increasing the likelihood of structural failure under load. In Brazilian accented English this could be described as “No So Goud”. The most common shoulder problem I see is kyphosis or a rounding forward of the shoulders and over-accentuation of the normal thoracic curve. I have not noticed much if any lordosis of the thoracic spine however it’s possible that this condition does not impede movements such as kipping and overhead squats and thus is largely ignored. Whatever the case, kyphosis appears to have a few different causes including: muscular imbalance and postural “failure”. Muscular imbalance occurs between scapular protractors such as the pectorals and latisimusdorsi muscles (strong) and scapular retractors such as the rhomboids and lower traps (weak). Postural failure is not a value judgment but an acknowledgement that hunching over a keyboard, sitting in chairs that slump one forward, riding bicycles, boxing and a host of other activities tend to round one forward to a much larger degree than one is opened backwards. Just as an aside, this is not intended as an in-depth exploration of the anatomy of the shoulder girdle and the potential structural pathologies that may accompany this complex. If you want to get hoity-toity on those topics give Kelly Starrett of San Francisco CrossFit an email. That guy is a genius and he certainly has the gift-of-gab regarding all things rehab and training. Tell him “Gaius Baltar” sent you.

Das Fix

Putting all the anatomy dookie aside, what EXACTLY does kyphosis mean for the athletes I (and you) work with? Do you need to know that someone has an imbalance between pectorals and rhomboid? Well, no. It’s great to know your anatomy but the issue with these folks is their movement is not right. This is how you discovered the problem in the first place. Tight shoulders that eventually lead to kyphosis are observable in two ways.

1. Overhead work such as pressing, jerks and overhead squats (OHS) is difficult if not impossible.

2. Kipping pull-ups are tough and lack the ability to store elastic energy in the shoulder girdle, particularly at the apex of the chest forward position of the kip.

In the case of the OHS an individual with tight shoulders is incapable of a normal squat even with an inconsequential load such as PVC. The individual pitches forward and additional loading is all but impossible. With regards to the kip the individual is unable to bring the head through the arms into the frontal plane during the forward portion of the kip. This greatly limits maximum power generation and the ability to recruit the hips for this whole body movement.

I’m a bit dense at times however it may be obvious to you folks that the movements that cause the most problems should be the ones that are needed most. Along this line of reasoning, when it became apparent that our clients were not strong enough we instituted a strength circuit that kicks off virtually all workouts. We mix squats, dead lifts, presses and weighted pull-ups doing a Starting Strength type of progression before some mixed modal metabolic conditioning. The result has been dramatic increase in strength and proficiency for our clients. Shocker, practice something and get bEtter at it! I’ve known for some time that our clients have problems with shoulder mobility yet it only occurred to me recently that dedicated mobility work before EVERY training session might be of benefit. The approach we have used is simple yet it has proven to be remarkably effective. Mixed into the strength work our clients have added 3-5 sets of 10 repetitions of: Shoulder dislocates, OHS and glide kips.

Shoulder Dislocates This movement is likely familiar to anyone with a pulse however there are some fine points that are frequently missed. One should start the dislocates using a dowel or piece of PVC and start at a hand width that is easy to pass the bar from the hips all the way to the back with a firm grip on the dowel. For some people this may be impossible to accomplish at any hand width. This crisis prone situation should invoke the Magic Coaching Spell “do your best”. Something that may shift this movement from impossible to doable is a fully active shoulder (shrug the traps HARD!), both when passing forward and backward. Do not explode through this movement, go easy and be persuasive. Look at this more like a long-term relationship that requires diligence and patience, not a one-night stand.

OHS For the purpose of shoulder mobility one should use as narrow a grip in the OHS as allows for the best form with regards to an upright torso and keeping the dowel over the ear and the heel. The feet should be between hip and shoulder width. For some this is not possible at present, and thus the need to do it to the best of ones ability. The chin should be neutral if not slightly down and forward. This will allow one to once again, fully activate the shoulders and drive the dowel up as much as possible. For the mobility challenged, descending into a full ass-to-ankles squat may produce extreme discomfort in the spinal erectors and mid-back. Good, there is hope. A key point is that EVERY repetition of this exercise can and should be uncomfortable. This should require focus and patience to execute correctly.

“Glide” Kip This is not technically a glide kip as it is known and performed in gymnastics. The movement we are looking for generates power in a similar fashion to the gymnastics glide kip however it is only a fraction of the power. That said, Greg Everett’s Big Fat Pull Up is a perfect illustration of the mobility necessary to generate an impressive amount of power in the kip. For some basic mechanics check out this video from CrossFit. The point of the glide kip in this context is to mobilize the shoulders. This may necessitate a very small movement in the beginning but it will allow for greater movement with practice. Individuals with tight shoulders are frequently reduced to dead hang only pull-ups or greatly muted kipping power due to a lack of flexibility. Adequate mobility allows for the storage and release of energy in the shoulder girdle. This is not only advantageous for sport and training but I think a lack of kipping leaves one open to shoulder pathology over time.

A basic coaching cue to initiate the kip: Starting from the dead hang position have the client simultaneously drive the bar away with the hands, and with a straight body elevate the toes forward. This should place the client in a suspended hollow position. One should now pull forward and drive the legs back. In quick Coach Speak this is “Push away, raise the toes! Pull under the bar!” Corny, but it works. The forward position will be the tough portion of the movement for the mobility challenged. Ease into this and do not over kip.

This whole sequence has proven effective for improving static and dynamic shoulder flexibility. Folks are OHS better and heavier and the mechanics of kipped pull-ups have improved. Overhead movements such as push presses and push jerks have also improved nicely. At what point should you discontinue this work with a client? If the individual is strong in OHS (5-10 reps at body weight), L-sit pull ups (10-this a great developer of scapular retractors) and kipped pull ups (30+) the individual likely has all the mobility necessary. So long as these movements make up a significant portion of the S&C curriculum they should maintain and even advance what is now a healthy shoulder.

I enjoy the challenge and the freedom this work affords me and I DO feel that I have attained a high level of understanding in one element of the generalist coaching: An eye for Good Movement. I’ve seen quite a number of cyclists, soccer players, stay-at-home-moms (both professional and amateur), ruggers…and from this experience I can spot “good movement” pretty quickly. Does someone have adequate hip and shoulder flexibility? Watch them overhead squat, even with just a broomstick, and you will know instantly. Shoulder mobility, flexibility and health are actually something I have zeroed in on lately as I have seen problems across all movement backgrounds, ages and in both genders. This has actually been surprising as folks can range from sedentary to athletic, obese to lean and they frequently have severe limitations in shoulder strength and mobility. These limitations not only impede progress in the gym but also frequently predispose the individual to further problems such as rotator cuff impingement and deteriorating posture. I’ve been tinkering with ways to address this problem but before we look at that let’s look at what is going on with the shoulder girdle itself.

Kyphosis

In a normal spine we have a structurally sound curve in the low back, with a counter curve in the thoracic region, and a final counter curve in the cervical region. From an engineering perspective arches such as those found in the human spine are remarkably strong and are capable of bearing tremendous loads. Perturbing the structure of the arch however causes the integrity to plummet, thus increasing the likelihood of structural failure under load. In Brazilian accented English this could be described as “No So Goud”. The most common shoulder problem I see is kyphosis or a rounding forward of the shoulders and over-accentuation of the normal thoracic curve. I have not noticed much if any lordosis of the thoracic spine however it’s possible that this condition does not impede movements such as kipping and overhead squats and thus is largely ignored. Whatever the case, kyphosis appears to have a few different causes including: muscular imbalance and postural “failure”. Muscular imbalance occurs between scapular protractors such as the pectorals and latisimusdorsi muscles (strong) and scapular retractors such as the rhomboids and lower traps (weak). Postural failure is not a value judgment but an acknowledgement that hunching over a keyboard, sitting in chairs that slump one forward, riding bicycles, boxing and a host of other activities tend to round one forward to a much larger degree than one is opened backwards. Just as an aside, this is not intended as an in-depth exploration of the anatomy of the shoulder girdle and the potential structural pathologies that may accompany this complex. If you want to get hoity-toity on those topics give Kelly Starrett of San Francisco CrossFit an email. That guy is a genius and he certainly has the gift-of-gab regarding all things rehab and training. Tell him “Gaius Baltar” sent you.

Das Fix

Putting all the anatomy dookie aside, what EXACTLY does kyphosis mean for the athletes I (and you) work with? Do you need to know that someone has an imbalance between pectorals and rhomboid? Well, no. It’s great to know your anatomy but the issue with these folks is their movement is not right. This is how you discovered the problem in the first place. Tight shoulders that eventually lead to kyphosis are observable in two ways.

1. Overhead work such as pressing, jerks and overhead squats (OHS) is difficult if not impossible.

2. Kipping pull-ups are tough and lack the ability to store elastic energy in the shoulder girdle, particularly at the apex of the chest forward position of the kip.

In the case of the OHS an individual with tight shoulders is incapable of a normal squat even with an inconsequential load such as PVC. The individual pitches forward and additional loading is all but impossible. With regards to the kip the individual is unable to bring the head through the arms into the frontal plane during the forward portion of the kip. This greatly limits maximum power generation and the ability to recruit the hips for this whole body movement.

I’m a bit dense at times however it may be obvious to you folks that the movements that cause the most problems should be the ones that are needed most. Along this line of reasoning, when it became apparent that our clients were not strong enough we instituted a strength circuit that kicks off virtually all workouts. We mix squats, dead lifts, presses and weighted pull-ups doing a Starting Strength type of progression before some mixed modal metabolic conditioning. The result has been dramatic increase in strength and proficiency for our clients. Shocker, practice something and get bEtter at it! I’ve known for some time that our clients have problems with shoulder mobility yet it only occurred to me recently that dedicated mobility work before EVERY training session might be of benefit. The approach we have used is simple yet it has proven to be remarkably effective. Mixed into the strength work our clients have added 3-5 sets of 10 repetitions of: Shoulder dislocates, OHS and glide kips.

Shoulder Dislocates This movement is likely familiar to anyone with a pulse however there are some fine points that are frequently missed. One should start the dislocates using a dowel or piece of PVC and start at a hand width that is easy to pass the bar from the hips all the way to the back with a firm grip on the dowel. For some people this may be impossible to accomplish at any hand width. This crisis prone situation should invoke the Magic Coaching Spell “do your best”. Something that may shift this movement from impossible to doable is a fully active shoulder (shrug the traps HARD!), both when passing forward and backward. Do not explode through this movement, go easy and be persuasive. Look at this more like a long-term relationship that requires diligence and patience, not a one-night stand.

OHS For the purpose of shoulder mobility one should use as narrow a grip in the OHS as allows for the best form with regards to an upright torso and keeping the dowel over the ear and the heel. The feet should be between hip and shoulder width. For some this is not possible at present, and thus the need to do it to the best of ones ability. The chin should be neutral if not slightly down and forward. This will allow one to once again, fully activate the shoulders and drive the dowel up as much as possible. For the mobility challenged, descending into a full ass-to-ankles squat may produce extreme discomfort in the spinal erectors and mid-back. Good, there is hope. A key point is that EVERY repetition of this exercise can and should be uncomfortable. This should require focus and patience to execute correctly.

“Glide” Kip This is not technically a glide kip as it is known and performed in gymnastics. The movement we are looking for generates power in a similar fashion to the gymnastics glide kip however it is only a fraction of the power. That said, Greg Everett’s Big Fat Pull Up is a perfect illustration of the mobility necessary to generate an impressive amount of power in the kip. For some basic mechanics check out this video from CrossFit. The point of the glide kip in this context is to mobilize the shoulders. This may necessitate a very small movement in the beginning but it will allow for greater movement with practice. Individuals with tight shoulders are frequently reduced to dead hang only pull-ups or greatly muted kipping power due to a lack of flexibility. Adequate mobility allows for the storage and release of energy in the shoulder girdle. This is not only advantageous for sport and training but I think a lack of kipping leaves one open to shoulder pathology over time.

A basic coaching cue to initiate the kip: Starting from the dead hang position have the client simultaneously drive the bar away with the hands, and with a straight body elevate the toes forward. This should place the client in a suspended hollow position. One should now pull forward and drive the legs back. In quick Coach Speak this is “Push away, raise the toes! Pull under the bar!” Corny, but it works. The forward position will be the tough portion of the movement for the mobility challenged. Ease into this and do not over kip.

This whole sequence has proven effective for improving static and dynamic shoulder flexibility. Folks are OHS better and heavier and the mechanics of kipped pull-ups have improved. Overhead movements such as push presses and push jerks have also improved nicely. At what point should you discontinue this work with a client? If the individual is strong in OHS (5-10 reps at body weight), L-sit pull ups (10-this a great developer of scapular retractors) and kipped pull ups (30+) the individual likely has all the mobility necessary. So long as these movements make up a significant portion of the S&C curriculum they should maintain and even advance what is now a healthy shoulder.

| Robb Wolf is the author of the best-selling book The Paleo Solution, co-founder of the Performance Menu, and co-owner of NorCal Strength & Conditioning. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date