Weightlifting Mesocycles Part 3: Power Phase for Weightlifters

Last month’s topic, the significance of general strength, is followed with this month’s topic of power. After four weeks of general preparation and four weeks of strength work, the process of converting this to power is critical. The definition of power can be interpreted as force times distance over time--so without increasing strength, the ability to move mass over a given distance in a short period of time all of the previous work will have been done for nothing. For most powerful athletes like weightlifters, throwers and sprinters, getting stronger is the key to getting more powerful. If athletes can apply more force, then they will be able to move a given amount of mass over a given distance faster. Therefore, a comprehensive GPP and strength phase is vital to getting more powerful. Consequently, in the power phase, the main focus will be on explosive, dynamic movements designed to increase power and take advantage of the previous two phases. This will be done by decreasing the amount of repetitions per set while increasing the intensity compared to the general preparation and strength phases. This article will focus on how Front Range Weightlifting Club transitions its athletes from the general strength phase to the power phase.

The Basic Structure

The two previous phases lasted to total of eight weeks. Similarly, the power phase will also be a total of four weeks, from eight weeks from the competition to five weeks out. As before, given the athletes are healthy and had productive GPP and strength cycles, the focus of the power phase include continual technique work for all of the movements along with an increased emphasis on the power movements and the classical lifts. Leg and pulling strength exercises are still emphasized, but with increased intensities. Therefore, athletes can expect a continued decrease in overall volume, though average intensity will continue to increase. Exercises that increase work capacity and basic cardiovascular conditioning, such as the circuits from the GPP and strength cycles, will be minimized, much to the athlete’s delight! The general warm-up followed by a more specific dynamic warm-up, plyometrics, the weightlifting exercises and core remain as before.

Warming up

A general warm-up of rowing, jumping rope or low level sprints are still included. Medicine ball, barbell, dumbbell, kettlebell or bodyweight circuits are minimized and typically exercises from these circuits are now performed individually. For example, instead of five to six exercises for ten reps in a circuit, that might be reduced to three to four exercises for six to eight reps with a period of rest between exercises. Furthermore, the focus will be on the more dynamic movements such as wall ball shots, med ball cleans, kettlebell snatches and swings or dumbbell muscle snatches or thrusters.

Plyometrics are still incorporated after the warm-up but with an emphasis on explosiveness rather than reactivity. Some examples of these would be a med ball slam plus a jump, dumbbell thrusters with a jump, dumbbell split jumps, squat jumps with the bar and the like. Again, the general warm-up and plyometrics should heighten the neuromuscular system and not fatigue it. It is better to err on the side of being conservative instead of tiring the athlete out for the main part of the workout. The entire warm-up including the plyos should take less than ten minutes with given rest periods.

Volume & Intensity

During the conversion to power, athletes are asked to increase the intensity of their movements. However, they are still asked to use the most amount of weight possible in their sets with good technique. As before, if technique breaks down, the weights are lowered to complete the sets and reps. The coach must remain steadfast in this area. Coaches can assure their athletes that in the competition phase they will be given the opportunity to attempt maximum weights. Athletes are still vulnerable to develop poor technical habits if given the opportunity to do so with the higher intensities.

In the power mesocycle, there will be three hard training weeks and a fourth recovery/unloading week as with the two prior mesocycles. Volume will continue to be non-linear, now varying between 170-225 repetitions per microcycle. Diversity between volume and intensity in the four microcycles will not have as great a disparity as previous Mesocycles, but the recovery/unloading microcycle of week four will be consistent with previous cycles and show less average volume, with greater average intensities, at or above 85% of the lifter’s one repetition maximum in the respective lifts. There will be an overall decrease in average volume for all lifts and movements. Volumes for traditional lifts and their derivatives will not be more than three repetitions per set while leg strengthening, pulling and overhead movements will vary between three and five reps.

Exercise selection in this cycle will be similar to the strength cycle. Lifts from different positions and complex lifts will still be used only with higher intensities and less volume. Further, lifts from blocks will be incorporated to stress rate of force development (RFD). Essentially, RFD refers to the speed at which force can be produced. Because there is no stretch reflex occurring research shows that the time for muscle activation decreases. Consequently, stronger athletes can produce more force quicker and therefore can move the bar faster.

Exercise Selection

Lt me restating the goals of this mesocycle: increased emphasis on proper technique in the classical lifts and power movements, introducing lifts from the blocks and continuing to increase leg, pulling and overhead strength. The following might be a typical microcycle for the power phase.

Day 1:

General warm-up: form running (30 meters)

• Skips

• Defensive slide

• Carioca

• Heel to butt

• Lateral bounds

• High knee bounds

• Build up

Specific warm-up: (rest 30-60 seconds between exercises)

• 8 Wall ball shots

• 8 Med ball cleans

• 8 DB thrusters

• 8 Kettlebell swings

Plyometric: DB split jumps: 2x16

Weightlifting workout:

1. Snatch balance: 4x4

2. Snatch from blocks: 4x3

3. Clean: 4x3

4. Front squats: 4x4

5. Core & Assistance:

• Weighted back extension: 2x8

• Handstand push-ups: 2x6-8

Total reps: 56

Easy form running exercises and a weighted plyometric make up the warm-up. Exercise 2, snatch from blocks, emphasizes RFD as described earlier. The coach should also make sure the movement is consistent with the movement from the floor. Clean is the next exercise. The main focus should be on technique, ensuring athletes are meeting the bar correctly and keeping the proper technique with as much weight as possible. Front squats are the last lifting exercise and core & assistance will finish out the workout.

Day 2:

General warm-up: Skipping rope or double unders for two minutes

Specific warm-up: (rest 30-60 seconds between exercises)

• 6 Ball slams

• 8 Kettlebell snatches, each arm

• 8 DB muscle snatches, below knee

• 6 Overhead squats with bar

Plyometric: DB thrusters with a jump: 3x8

Weightlifting workout:

1. Snatch from above knee: 4x3

2. Clean + power jerk: 5x2+3

3. Snatch pulls from a 2 inch board: 2x5, 2x4

4. Push press: 4x4

5. Core & Assistance:

• V-ups: 2x10

• Pull-ups: 2x8

Total reps: 71

Following the warm up and plyo, snatch from above knee-a technical movement-is the first lifting exercise. It is vital, since athletes are still trying to perfect the snatch movement. Athletes, through years of training, continue practicing the movement to make it autonomous, or automatic. The sets and reps allow athletes to use heavier weights than in previous cycles yet are still benefitting from the technical aspect through the eyes of the coach.

Exercise 2, clean + power jerk, allows variation from the classical clean & jerk. Giving a variety of lifts to athletes permits them to become better all around lifters. The power jerk teaches athletes the proper dip and drive, as in the jerk. However, is not as forgiving. Consequently, if athletes perform the movement with a flaw, they will most likely miss the lift.

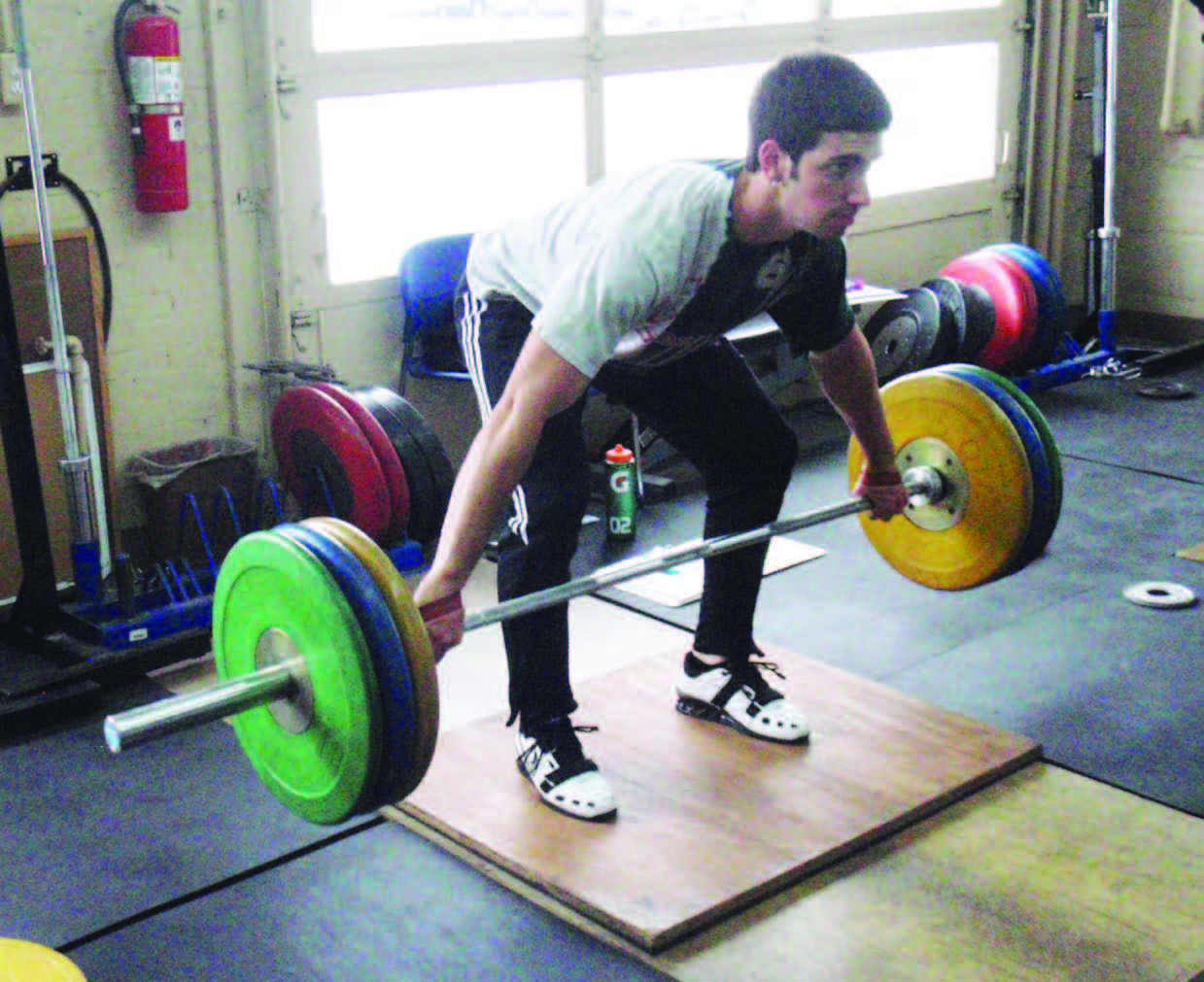

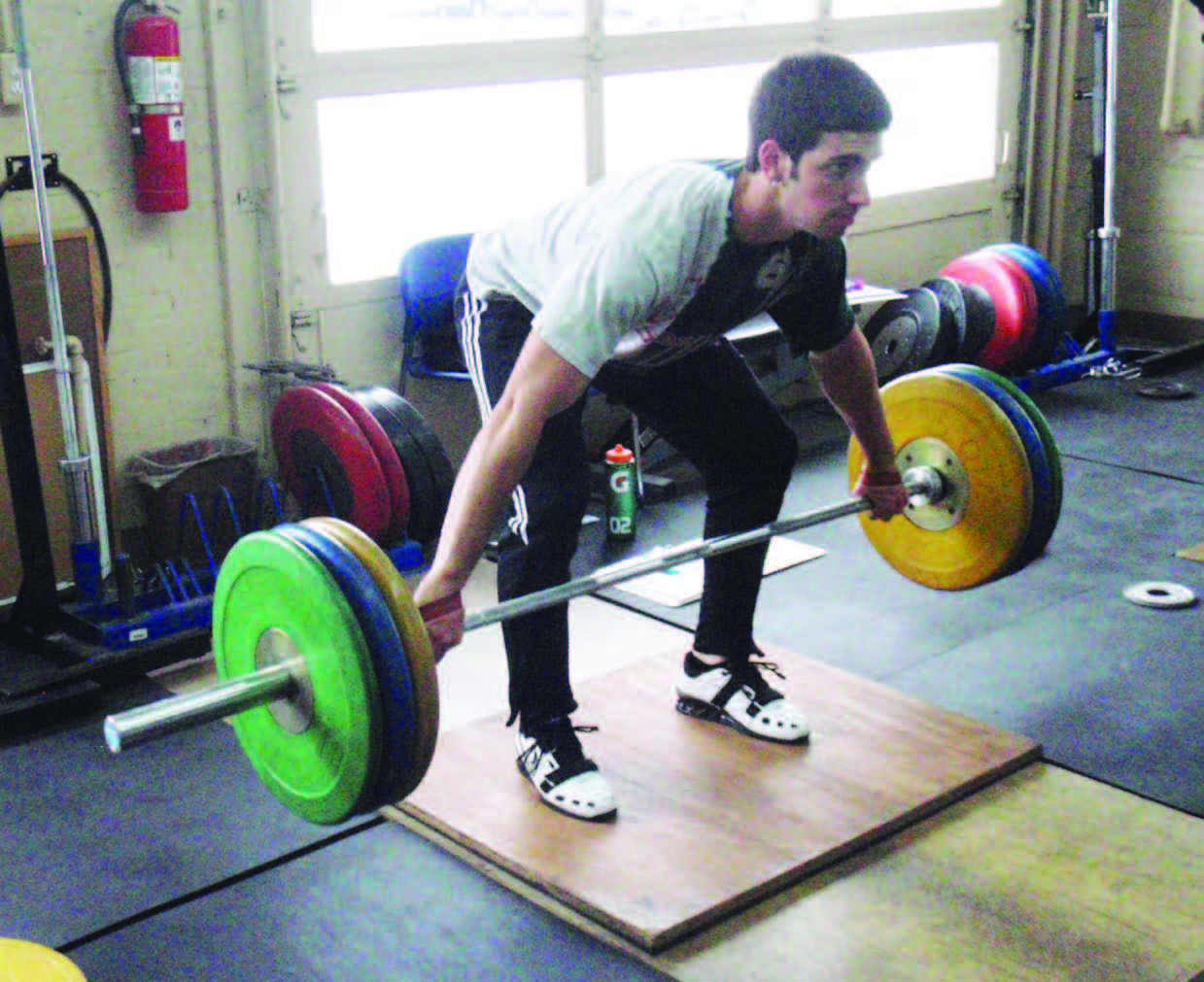

Another variation of an everyday exercise is snatch pulls from an elevated board. Although the board has a minimal thickness of 2 inches, if athletes do not set up properly then more stress will go on the back and therefore, throw off the movement. Again, the more variety athletes see in their programs the more prepared they will be on the platform if the lift does not go according to plan. Athletes should do two sets of five reps and then increase the weight for the two sets of four. Push press, while not as important as in the GPP and general strength phases, is still important enough to include in the power phase.

Day 3:

General warm-up: Row 500 meters

Specific warm-up: (rest 30-60 seconds between exercises)

• 8 Kettlebell sumo deadlift high pulls

• 8 Kettlebell swings

• 8 Muscle snatches with bar- below knee

• 8 Squat to press with bar

Plyometric: Ball slam + jump: 3x6

Weightlifting workout:

1. Overhead squat: 1x5, 1x4, 1x3

2. Snatch: 1x3, 4x2

3. Clean & jerk: 2x3+2, 3x2+2

4. Clean pulls: 2x5, 2x4

5. Squats: 4x5

6. Core & Assistance:

• Good mornings: 3x5

• Ring dips: 2x8

Total reps: 86

Total weekly volume: 213 reps

Following the row and specific warm-up, a great neuromuscular plyometric is ball slam + jump. Athletes lift a slam ball overhead so their biceps are past their ears and proceed to slam the ball to the ground following it down into a full squat then doing a maximal squat jump (without the ball). A brief yet effective exercise!

As with any overhead movement in the power phase, the overhead squat continues to give confidence to the lifter by increasing the intensity. These overhead movements, stressing strength and stability, are kept in the program until the final cycle, the competition phase. The overhead squat is a good transition exercise for the snatch, which is the next exercise. Again, as reps decrease throughout the set, more weight should be added until technique breaks down.

The classical clean & jerk follows the snatch, so athletes begin to get used to performing both movements in the same workout, as in competition. Day 3 in each microcyle in the power phase will have both classical movements in the same workout. By not having both movements in the same workout since perhaps the last competition, this will not only condition the athletes for the competition phase but will psychologically prepare them for the competition itself.

Athletes can work up to nearly 100% in the clean pulls. Once more, athletes should begin to feel heavier weights on the bar to better prepare them for the competition phase. This is also a good indicator of how much stronger they have gotten over the last two phases. Squats reps will begin to lessen as the power phase moves closer to the competition phase however; caution should be shown that singles and doubles should not be put in too early in the power phase. Good mornings, a solid posterior chain exercise and ring dips round out the workout.

In Conclusion

A comprehensive power phase should give the coach a very good indicator of how much stronger and more conditioned his athletes are. As athletes begin to incorporate more specific lifts related to power and do more classical movements, it should become apparent how effective the GPP and general strength phases were. There is no substitute for hard work and the power phase will give the coach a very good marker of just how hard his athletes have worked in the previous eight weeks. With younger athletes, each power phase should bring new personal records and give extraordinary confidence to them. This, in turn, will set the athletes up for a successful competition phase.

The Basic Structure

The two previous phases lasted to total of eight weeks. Similarly, the power phase will also be a total of four weeks, from eight weeks from the competition to five weeks out. As before, given the athletes are healthy and had productive GPP and strength cycles, the focus of the power phase include continual technique work for all of the movements along with an increased emphasis on the power movements and the classical lifts. Leg and pulling strength exercises are still emphasized, but with increased intensities. Therefore, athletes can expect a continued decrease in overall volume, though average intensity will continue to increase. Exercises that increase work capacity and basic cardiovascular conditioning, such as the circuits from the GPP and strength cycles, will be minimized, much to the athlete’s delight! The general warm-up followed by a more specific dynamic warm-up, plyometrics, the weightlifting exercises and core remain as before.

Warming up

A general warm-up of rowing, jumping rope or low level sprints are still included. Medicine ball, barbell, dumbbell, kettlebell or bodyweight circuits are minimized and typically exercises from these circuits are now performed individually. For example, instead of five to six exercises for ten reps in a circuit, that might be reduced to three to four exercises for six to eight reps with a period of rest between exercises. Furthermore, the focus will be on the more dynamic movements such as wall ball shots, med ball cleans, kettlebell snatches and swings or dumbbell muscle snatches or thrusters.

Plyometrics are still incorporated after the warm-up but with an emphasis on explosiveness rather than reactivity. Some examples of these would be a med ball slam plus a jump, dumbbell thrusters with a jump, dumbbell split jumps, squat jumps with the bar and the like. Again, the general warm-up and plyometrics should heighten the neuromuscular system and not fatigue it. It is better to err on the side of being conservative instead of tiring the athlete out for the main part of the workout. The entire warm-up including the plyos should take less than ten minutes with given rest periods.

Volume & Intensity

During the conversion to power, athletes are asked to increase the intensity of their movements. However, they are still asked to use the most amount of weight possible in their sets with good technique. As before, if technique breaks down, the weights are lowered to complete the sets and reps. The coach must remain steadfast in this area. Coaches can assure their athletes that in the competition phase they will be given the opportunity to attempt maximum weights. Athletes are still vulnerable to develop poor technical habits if given the opportunity to do so with the higher intensities.

In the power mesocycle, there will be three hard training weeks and a fourth recovery/unloading week as with the two prior mesocycles. Volume will continue to be non-linear, now varying between 170-225 repetitions per microcycle. Diversity between volume and intensity in the four microcycles will not have as great a disparity as previous Mesocycles, but the recovery/unloading microcycle of week four will be consistent with previous cycles and show less average volume, with greater average intensities, at or above 85% of the lifter’s one repetition maximum in the respective lifts. There will be an overall decrease in average volume for all lifts and movements. Volumes for traditional lifts and their derivatives will not be more than three repetitions per set while leg strengthening, pulling and overhead movements will vary between three and five reps.

Exercise selection in this cycle will be similar to the strength cycle. Lifts from different positions and complex lifts will still be used only with higher intensities and less volume. Further, lifts from blocks will be incorporated to stress rate of force development (RFD). Essentially, RFD refers to the speed at which force can be produced. Because there is no stretch reflex occurring research shows that the time for muscle activation decreases. Consequently, stronger athletes can produce more force quicker and therefore can move the bar faster.

Exercise Selection

Lt me restating the goals of this mesocycle: increased emphasis on proper technique in the classical lifts and power movements, introducing lifts from the blocks and continuing to increase leg, pulling and overhead strength. The following might be a typical microcycle for the power phase.

Day 1:

General warm-up: form running (30 meters)

• Skips

• Defensive slide

• Carioca

• Heel to butt

• Lateral bounds

• High knee bounds

• Build up

Specific warm-up: (rest 30-60 seconds between exercises)

• 8 Wall ball shots

• 8 Med ball cleans

• 8 DB thrusters

• 8 Kettlebell swings

Plyometric: DB split jumps: 2x16

Weightlifting workout:

1. Snatch balance: 4x4

2. Snatch from blocks: 4x3

3. Clean: 4x3

4. Front squats: 4x4

5. Core & Assistance:

• Weighted back extension: 2x8

• Handstand push-ups: 2x6-8

Total reps: 56

Easy form running exercises and a weighted plyometric make up the warm-up. Exercise 2, snatch from blocks, emphasizes RFD as described earlier. The coach should also make sure the movement is consistent with the movement from the floor. Clean is the next exercise. The main focus should be on technique, ensuring athletes are meeting the bar correctly and keeping the proper technique with as much weight as possible. Front squats are the last lifting exercise and core & assistance will finish out the workout.

Day 2:

General warm-up: Skipping rope or double unders for two minutes

Specific warm-up: (rest 30-60 seconds between exercises)

• 6 Ball slams

• 8 Kettlebell snatches, each arm

• 8 DB muscle snatches, below knee

• 6 Overhead squats with bar

Plyometric: DB thrusters with a jump: 3x8

Weightlifting workout:

1. Snatch from above knee: 4x3

2. Clean + power jerk: 5x2+3

3. Snatch pulls from a 2 inch board: 2x5, 2x4

4. Push press: 4x4

5. Core & Assistance:

• V-ups: 2x10

• Pull-ups: 2x8

Total reps: 71

Following the warm up and plyo, snatch from above knee-a technical movement-is the first lifting exercise. It is vital, since athletes are still trying to perfect the snatch movement. Athletes, through years of training, continue practicing the movement to make it autonomous, or automatic. The sets and reps allow athletes to use heavier weights than in previous cycles yet are still benefitting from the technical aspect through the eyes of the coach.

Exercise 2, clean + power jerk, allows variation from the classical clean & jerk. Giving a variety of lifts to athletes permits them to become better all around lifters. The power jerk teaches athletes the proper dip and drive, as in the jerk. However, is not as forgiving. Consequently, if athletes perform the movement with a flaw, they will most likely miss the lift.

Another variation of an everyday exercise is snatch pulls from an elevated board. Although the board has a minimal thickness of 2 inches, if athletes do not set up properly then more stress will go on the back and therefore, throw off the movement. Again, the more variety athletes see in their programs the more prepared they will be on the platform if the lift does not go according to plan. Athletes should do two sets of five reps and then increase the weight for the two sets of four. Push press, while not as important as in the GPP and general strength phases, is still important enough to include in the power phase.

Day 3:

General warm-up: Row 500 meters

Specific warm-up: (rest 30-60 seconds between exercises)

• 8 Kettlebell sumo deadlift high pulls

• 8 Kettlebell swings

• 8 Muscle snatches with bar- below knee

• 8 Squat to press with bar

Plyometric: Ball slam + jump: 3x6

Weightlifting workout:

1. Overhead squat: 1x5, 1x4, 1x3

2. Snatch: 1x3, 4x2

3. Clean & jerk: 2x3+2, 3x2+2

4. Clean pulls: 2x5, 2x4

5. Squats: 4x5

6. Core & Assistance:

• Good mornings: 3x5

• Ring dips: 2x8

Total reps: 86

Total weekly volume: 213 reps

Following the row and specific warm-up, a great neuromuscular plyometric is ball slam + jump. Athletes lift a slam ball overhead so their biceps are past their ears and proceed to slam the ball to the ground following it down into a full squat then doing a maximal squat jump (without the ball). A brief yet effective exercise!

As with any overhead movement in the power phase, the overhead squat continues to give confidence to the lifter by increasing the intensity. These overhead movements, stressing strength and stability, are kept in the program until the final cycle, the competition phase. The overhead squat is a good transition exercise for the snatch, which is the next exercise. Again, as reps decrease throughout the set, more weight should be added until technique breaks down.

The classical clean & jerk follows the snatch, so athletes begin to get used to performing both movements in the same workout, as in competition. Day 3 in each microcyle in the power phase will have both classical movements in the same workout. By not having both movements in the same workout since perhaps the last competition, this will not only condition the athletes for the competition phase but will psychologically prepare them for the competition itself.

Athletes can work up to nearly 100% in the clean pulls. Once more, athletes should begin to feel heavier weights on the bar to better prepare them for the competition phase. This is also a good indicator of how much stronger they have gotten over the last two phases. Squats reps will begin to lessen as the power phase moves closer to the competition phase however; caution should be shown that singles and doubles should not be put in too early in the power phase. Good mornings, a solid posterior chain exercise and ring dips round out the workout.

In Conclusion

A comprehensive power phase should give the coach a very good indicator of how much stronger and more conditioned his athletes are. As athletes begin to incorporate more specific lifts related to power and do more classical movements, it should become apparent how effective the GPP and general strength phases were. There is no substitute for hard work and the power phase will give the coach a very good marker of just how hard his athletes have worked in the previous eight weeks. With younger athletes, each power phase should bring new personal records and give extraordinary confidence to them. This, in turn, will set the athletes up for a successful competition phase.

| Paul Fleschler is the owner of Front Range Sports Performance & Fitness and RedRocks CrossFit in Colorado Springs. He earned a masters degree in Motor Control and Learning from Indiana University, is a Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist and USA Weightlifting Senior International Coach where he has represented the United States at several international weightlifting competitions as Head and Assistant Coach. As an athlete, Paul’s greatest honor was representing the United States at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Paul is the former Men’s National Coach and former Men’s and Women’s Resident Coach at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs. He also served in a supportive role for USA Weightlifting at the 2004 and 2008 Olympic Games. Paul assisted with 20 varsity sports at Indiana University, and served as the Head Strength Coordinator for Indiana University Basketball. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date