Olympic Weightlifting: The “Power Positionâ€

For those who have attended any of my seminars or who have trained with me, the term “power position” will be all too familiar. It is engrained in your mind and body by the end of the day’s session through executing repetition after repetition. The power position is arguably the single most important aspect of the snatch or the c+j. Unfortunately, in the years I’ve spent training and now coaching the movements, it seems this portion of the movement is widely ignored by athletes and coaches, especially in the CrossFit arena. The astonishing difference experienced by the athlete once the power position has been either taught or reinforced is like the difference between night and day. It alone can fix many pre-existing errors such as an early arm-pull or the feeling of losing the weight forward. Though tough to describe in writing and illustrations, it is the goal of this article to define the power position, describe why it’s important, what occurs if it is not practiced, and how to apply it to your technique.

Defined

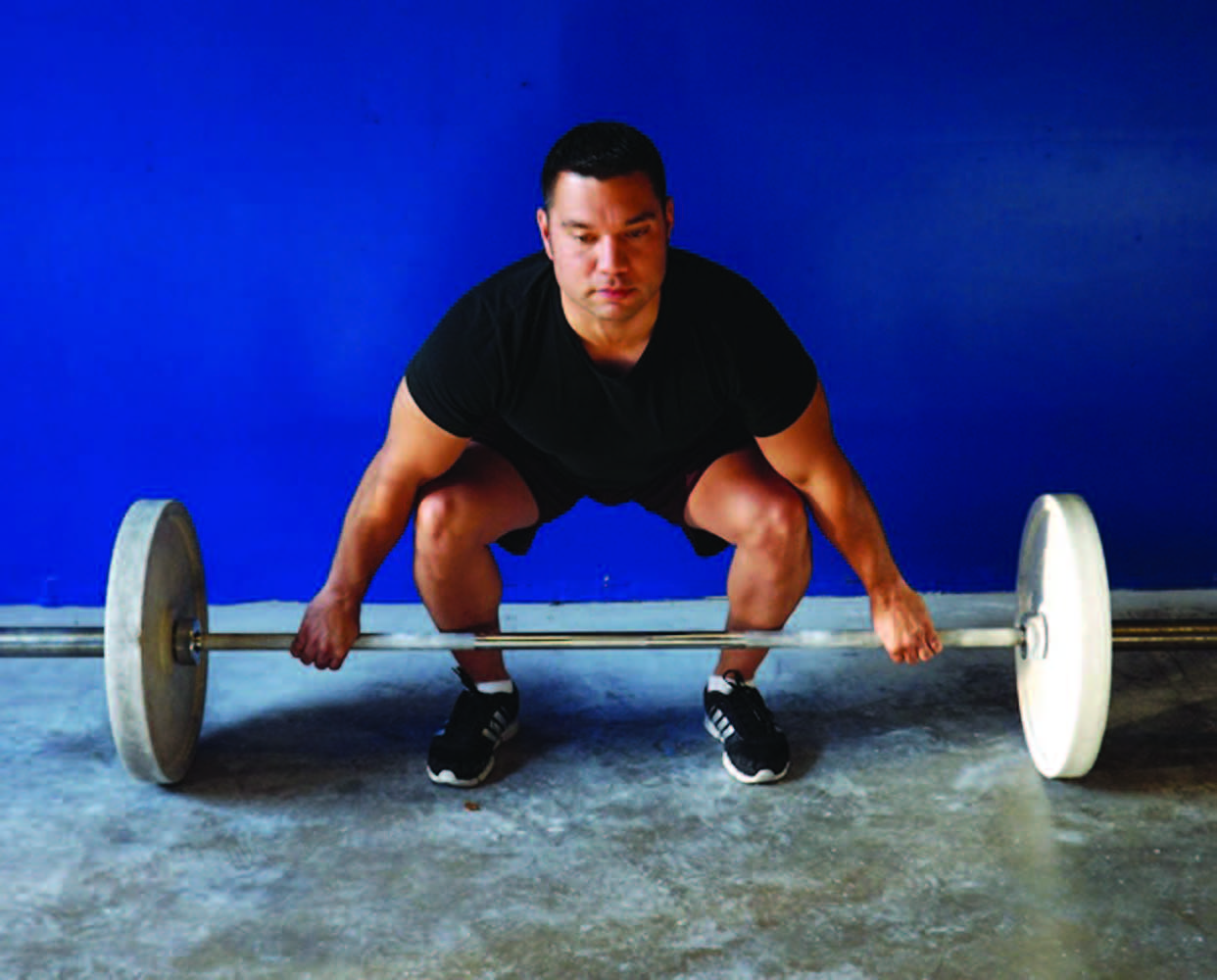

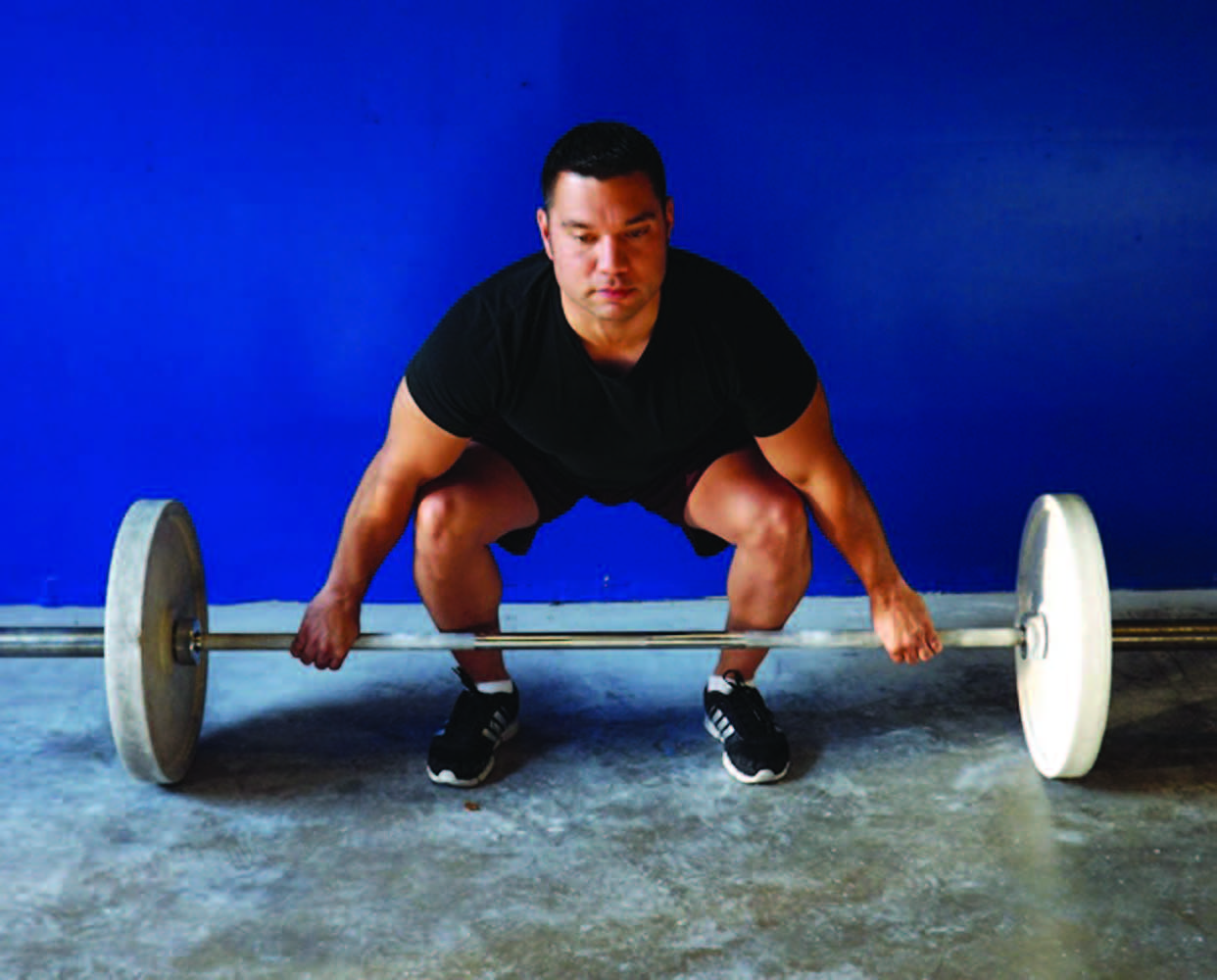

The power position, once referred to as the “scoop” or “scooping,” is the point during the snatch or clean where the lifter’s torso is erect with knees slightly bent, flat footed, and the bar is in contact with the top of the thighs. Have you seen an elite lifter appear to “smack” the bar off their thighs and it appears to just catapult overhead or to the shoulders? Well, they are, except the contact isn’t the primary goal of the movement, which is why beginners should never try to directly mimic this precise act as it could cause errors in other portions of the lift. The reason the “smacking” looks the way it does is because the lifter is practicing the use of the power position where the bar will make contact with the lifter. After learning the power position correctly, hopefully from day one, the lifter will develop the ability to hit the power position each time, maximizing his or her ability to generate the great explosion required to execute a maximal effort lift. The “smacking” is a secondary cause.

Why It’s Important

The power position is so important because:

a) It allows the athlete to maintain the bar close to the body, which gives the athlete control of the center of gravity, thus optimizing the force applied to the bar.

b) It allows the lifter to be in the best position to jump or complete a triple joint extension, a term most are familiar with, for the second pull, and

c) It properly prepares the lifter to land in the best receiving position that follows, be it the overhead squat for the snatch or the front squat for the clean.

During the start position, you should have been taught to begin with the barbell against the shins. Failure to do so causes the bar to roll out in front of the lifter, and we all know how extremely difficult that makes it on the part of the athlete to successfully lift the weight. It is kind of like carrying your groceries out in front of you with locked arms rather than carrying them against your chest; a waste of energy and completely inefficient. Of course, the goal is not for the lifter to have bruises, scrapes or wounds on their shins from dragging the barbell against their leg as they lift off the ground, but while learning to control the barbell, you may find your shins a nice shade of black and blue! The closer the barbell is to the body the more control the athlete has maximizing the force applied during the lift.

Therefore, wouldn’t it make sense for the barbell to travel just as close to the body the rest of the lift? The answer is an emphatic YES and hitting the power position accomplishes this goal. It’s true that while picking up the barbell the center of gravity (if considering the lifter and barbell as a single unit) is towards whichever is heavier; the lifter or the barbell. Ensuring the athlete practices the power position will keep from letting that center of gravity shift further towards the bar, pulling the lifter forward, as it gets heavier.

As noted above, the power position places the lifter in the best possible position to conduct the second pull, also known as the triple joint extension. If the lifter doesn’t use the power position, they will more than likely be “arm pulling” [PHOTO 4], or bending the arms too soon while still bent over. This puts the bar forward. Try jumping or conducting the second pull when the bar is forward.

Where will you and the bar end up? The answer is further in front of where you started and unable to receive it properly, snatch or clean, instead of vertical, which is where you need to land. Remember in the definition above, the power position is when “the lifter is erect with knees slightly bent, flat footed….” Lastly, with the lifter in the right position prior to the jump, the bar will then end exactly where the lifter needs the bar: directly overhead in the snatch or shelved right onto the shoulders in the clean. Perfect!

Consequences If Not Used

Failure to utilize the power position technique will undoubtedly cause the following errors:

• forward placement of the bar, as a result having the bar win over the athlete,

• slow the speed of the bar

• cause the athlete to bend arms too soon

• reduction in power output

• ruin the timing/ability to receive the bar in the correct position.

Remember, keeping the bar close to the body at all times is essential. The only way to ensure this is accomplished at the height of the thighs is with the institution of the power position. Not having it means the bar is left out in front of the lifter after the first pull (ground to the knees). Since our arms are not as strong as our hips, legs and buttocks (dominant muscles during power position), the arms alone will not be able to generate the speed and power needed to elevate that bar. The arms will try, which is why they bend too soon, but they will fail. This will in turn keep the athlete from truly producing enough velocity to make the bar weightless long enough to receive it. Thus, the landing or receiving portion of the snatch and clean will be rocky, unstable, and so awkward as to compromise the overall technique and likely cause a missed attempt.

Applying It To Your Technique

If you’re not already using the power position, I have hopefully now convinced you to do so. The most efficient way to learn this great tool is to build into it with progressions. Start with an empty bar, not a PVC pipe or dowel rod, as the bar will have just a bit of resistance to let you feel the movement. It isn’t necessary to belabor the proper progressions in this article, which is certainly the method used in my seminars, as I would need more space and illustrations. However, in a short and concise manner, I can recommend to start with the posture associated with the power position. From this position, with straight arms, jump the bar up from the thighs and into the receiving position. In the snatch, if you lock out overhead simultaneously as you land on your feet, you’ll get a sense of the effectiveness of this technique. In the clean, rack the bar on the shoulders with elbows pointing as straight forward as possible at the same time you land, which will also result in the same feeling. Reset and repeat several more times until you feel consistent. Then try it from the hang position. Execute the same thing, but after you hit any hang position, making sure to return to the power position before actually jumping and receiving the bar. After several reps and sets of consistency, you can then try lifting from the ground.

Keep in mind that when you lift from the ground, you must hit all the positions including the power position prior to initiating the “jump” and “receive” steps. You’ll know the very first time if you were successful. It is suggested that the athlete try several reps of slow motion execution to ensure all the positions are hit before jumping and receiving the bar. Practice your speed while hitting the positions, and then gradually increase the load on the bar.

It won’t be long before the new power position implementation will be a normal part of the athletes’ new technique. The challenge will be the first time a 1RM is attempted. The impatient will undoubtedly rush the form, bend the arms, miss the power position, and revert back to their old ways. So ensure the athlete has added speed and load while maintaining consistency for a good period of time before attempting serious loads with the new power position.

Defined

The power position, once referred to as the “scoop” or “scooping,” is the point during the snatch or clean where the lifter’s torso is erect with knees slightly bent, flat footed, and the bar is in contact with the top of the thighs. Have you seen an elite lifter appear to “smack” the bar off their thighs and it appears to just catapult overhead or to the shoulders? Well, they are, except the contact isn’t the primary goal of the movement, which is why beginners should never try to directly mimic this precise act as it could cause errors in other portions of the lift. The reason the “smacking” looks the way it does is because the lifter is practicing the use of the power position where the bar will make contact with the lifter. After learning the power position correctly, hopefully from day one, the lifter will develop the ability to hit the power position each time, maximizing his or her ability to generate the great explosion required to execute a maximal effort lift. The “smacking” is a secondary cause.

Why It’s Important

The power position is so important because:

a) It allows the athlete to maintain the bar close to the body, which gives the athlete control of the center of gravity, thus optimizing the force applied to the bar.

b) It allows the lifter to be in the best position to jump or complete a triple joint extension, a term most are familiar with, for the second pull, and

c) It properly prepares the lifter to land in the best receiving position that follows, be it the overhead squat for the snatch or the front squat for the clean.

During the start position, you should have been taught to begin with the barbell against the shins. Failure to do so causes the bar to roll out in front of the lifter, and we all know how extremely difficult that makes it on the part of the athlete to successfully lift the weight. It is kind of like carrying your groceries out in front of you with locked arms rather than carrying them against your chest; a waste of energy and completely inefficient. Of course, the goal is not for the lifter to have bruises, scrapes or wounds on their shins from dragging the barbell against their leg as they lift off the ground, but while learning to control the barbell, you may find your shins a nice shade of black and blue! The closer the barbell is to the body the more control the athlete has maximizing the force applied during the lift.

Therefore, wouldn’t it make sense for the barbell to travel just as close to the body the rest of the lift? The answer is an emphatic YES and hitting the power position accomplishes this goal. It’s true that while picking up the barbell the center of gravity (if considering the lifter and barbell as a single unit) is towards whichever is heavier; the lifter or the barbell. Ensuring the athlete practices the power position will keep from letting that center of gravity shift further towards the bar, pulling the lifter forward, as it gets heavier.

As noted above, the power position places the lifter in the best possible position to conduct the second pull, also known as the triple joint extension. If the lifter doesn’t use the power position, they will more than likely be “arm pulling” [PHOTO 4], or bending the arms too soon while still bent over. This puts the bar forward. Try jumping or conducting the second pull when the bar is forward.

Where will you and the bar end up? The answer is further in front of where you started and unable to receive it properly, snatch or clean, instead of vertical, which is where you need to land. Remember in the definition above, the power position is when “the lifter is erect with knees slightly bent, flat footed….” Lastly, with the lifter in the right position prior to the jump, the bar will then end exactly where the lifter needs the bar: directly overhead in the snatch or shelved right onto the shoulders in the clean. Perfect!

Consequences If Not Used

Failure to utilize the power position technique will undoubtedly cause the following errors:

• forward placement of the bar, as a result having the bar win over the athlete,

• slow the speed of the bar

• cause the athlete to bend arms too soon

• reduction in power output

• ruin the timing/ability to receive the bar in the correct position.

Remember, keeping the bar close to the body at all times is essential. The only way to ensure this is accomplished at the height of the thighs is with the institution of the power position. Not having it means the bar is left out in front of the lifter after the first pull (ground to the knees). Since our arms are not as strong as our hips, legs and buttocks (dominant muscles during power position), the arms alone will not be able to generate the speed and power needed to elevate that bar. The arms will try, which is why they bend too soon, but they will fail. This will in turn keep the athlete from truly producing enough velocity to make the bar weightless long enough to receive it. Thus, the landing or receiving portion of the snatch and clean will be rocky, unstable, and so awkward as to compromise the overall technique and likely cause a missed attempt.

Applying It To Your Technique

If you’re not already using the power position, I have hopefully now convinced you to do so. The most efficient way to learn this great tool is to build into it with progressions. Start with an empty bar, not a PVC pipe or dowel rod, as the bar will have just a bit of resistance to let you feel the movement. It isn’t necessary to belabor the proper progressions in this article, which is certainly the method used in my seminars, as I would need more space and illustrations. However, in a short and concise manner, I can recommend to start with the posture associated with the power position. From this position, with straight arms, jump the bar up from the thighs and into the receiving position. In the snatch, if you lock out overhead simultaneously as you land on your feet, you’ll get a sense of the effectiveness of this technique. In the clean, rack the bar on the shoulders with elbows pointing as straight forward as possible at the same time you land, which will also result in the same feeling. Reset and repeat several more times until you feel consistent. Then try it from the hang position. Execute the same thing, but after you hit any hang position, making sure to return to the power position before actually jumping and receiving the bar. After several reps and sets of consistency, you can then try lifting from the ground.

Keep in mind that when you lift from the ground, you must hit all the positions including the power position prior to initiating the “jump” and “receive” steps. You’ll know the very first time if you were successful. It is suggested that the athlete try several reps of slow motion execution to ensure all the positions are hit before jumping and receiving the bar. Practice your speed while hitting the positions, and then gradually increase the load on the bar.

It won’t be long before the new power position implementation will be a normal part of the athletes’ new technique. The challenge will be the first time a 1RM is attempted. The impatient will undoubtedly rush the form, bend the arms, miss the power position, and revert back to their old ways. So ensure the athlete has added speed and load while maintaining consistency for a good period of time before attempting serious loads with the new power position.

|

Daniel Camargo is a USAW International Coach and a 22-year veteran in the sport of Olympic Weightlifting. As an athlete Camargo was a 3-time U.S. Junior World Team Member and represented U.S.A. in 9 other international competitions. He also set three junior American Records. Now in his 14th year as a head coach, Camargo has produced several State, Collegiate and National Champions, as well as 12 athletes who themselves represented the United States in international competitions. In 2009, he was selected as Team Leader and Coach of Team USA and spent 10 days in Romania where he led the U.S. Team to the Junior World Weightlifting Championships. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date