Developing Efficiency in Strongman for All Sizes: Seven Tips For Athletes, Big & Small

The sport of Strongman is dominated with images of 300+ pound behemoths lifting, carrying, dragging and pressing all that stands in their way. What many don’t realize is that the sport doesn’t require Titan-like bone structure. There are weight classes in the amateur ranks ranging from less than 175 pounds to over 300. While it is true that a “strongman” needs to be strong for competitive participation in the sport, the combination of other general athletic qualities like power and mobility are what make some competitors better than others. The sport requires individuals to endure pain, focus through exhaustion, develop extreme levels of muscular tension, and still move quickly.

When we look at the best in the sport, like Brian Shaw, Derek Poundstone, or Mariusz Pudzianowski, not only are these athletes incredibly strong, but they also move surprisingly well. This is not reflected in most strongman competitions at the amateur level, though. Many of the amateur competitors have a training background rooted solely in powerlifting and often move in a way that shows their neglect of other athletic qualities. Smaller trainees and athletes will find that they are far more competitive with the big guys if they take the time to learn how to move well and perform lifts efficiently, as opposed to neglecting anything outside powerlifting, as so many do. Additionally, the big fellas would also be served well to take the following considerations to heart in their training and practice.

Strongman is more multidimensional than just absolute strength. My success in the sport has more to do with my speed and mobility than my numbers in the weight room. I am certainly not the strongest in the sense of pounds on the bar in the weight room, but by lifting and moving more efficiently than other competitors, I have been able to go further in the sport. The following considerations reflect some training aspects that can help those looking to begin or continue with strongman perform better by training to be more efficient as athletes.

Tip #1: Learn the Basic Moves

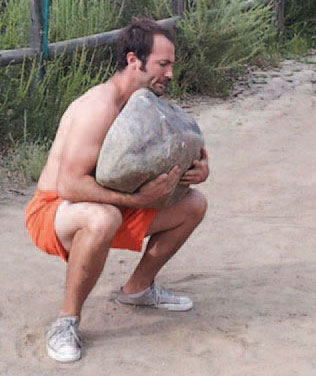

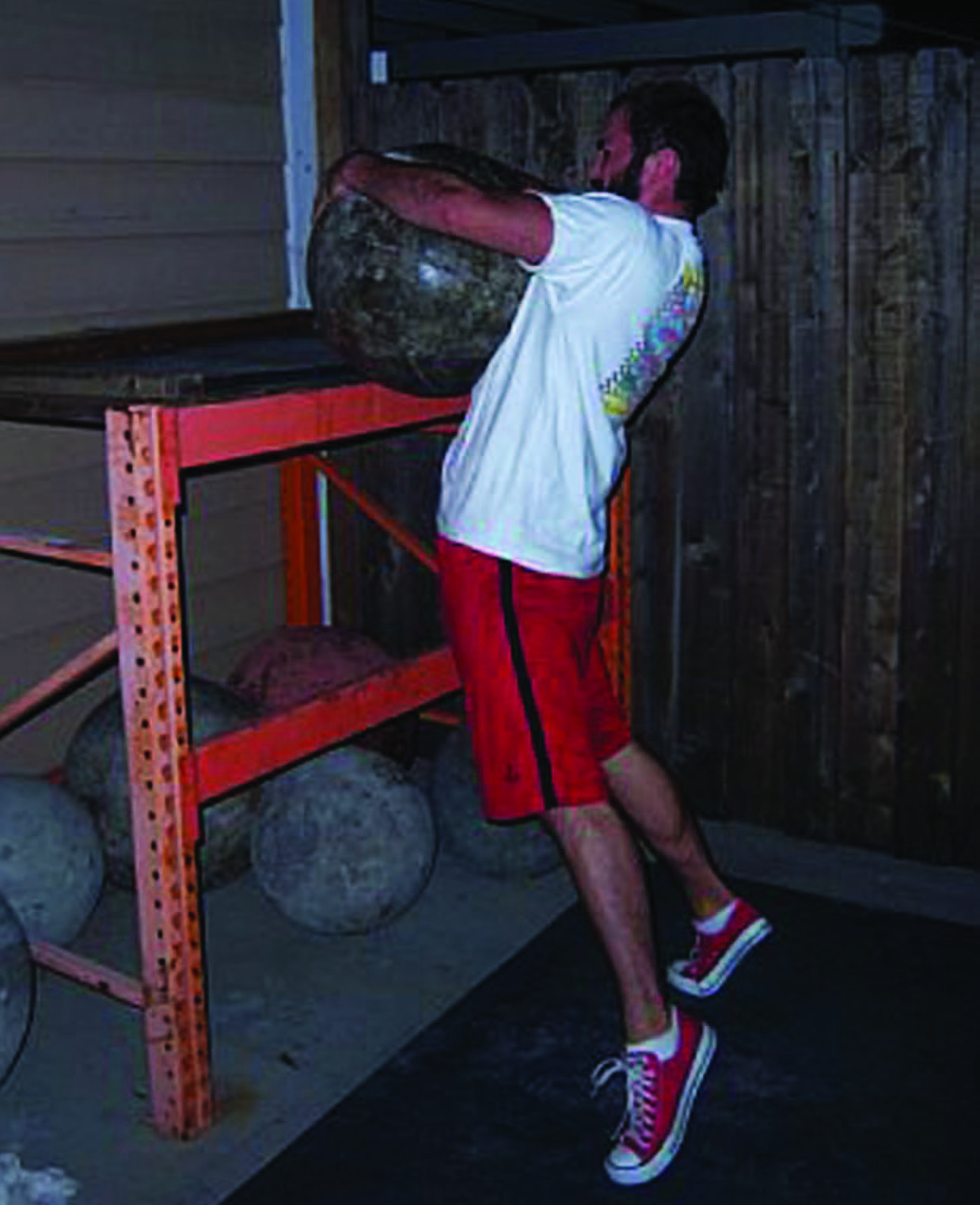

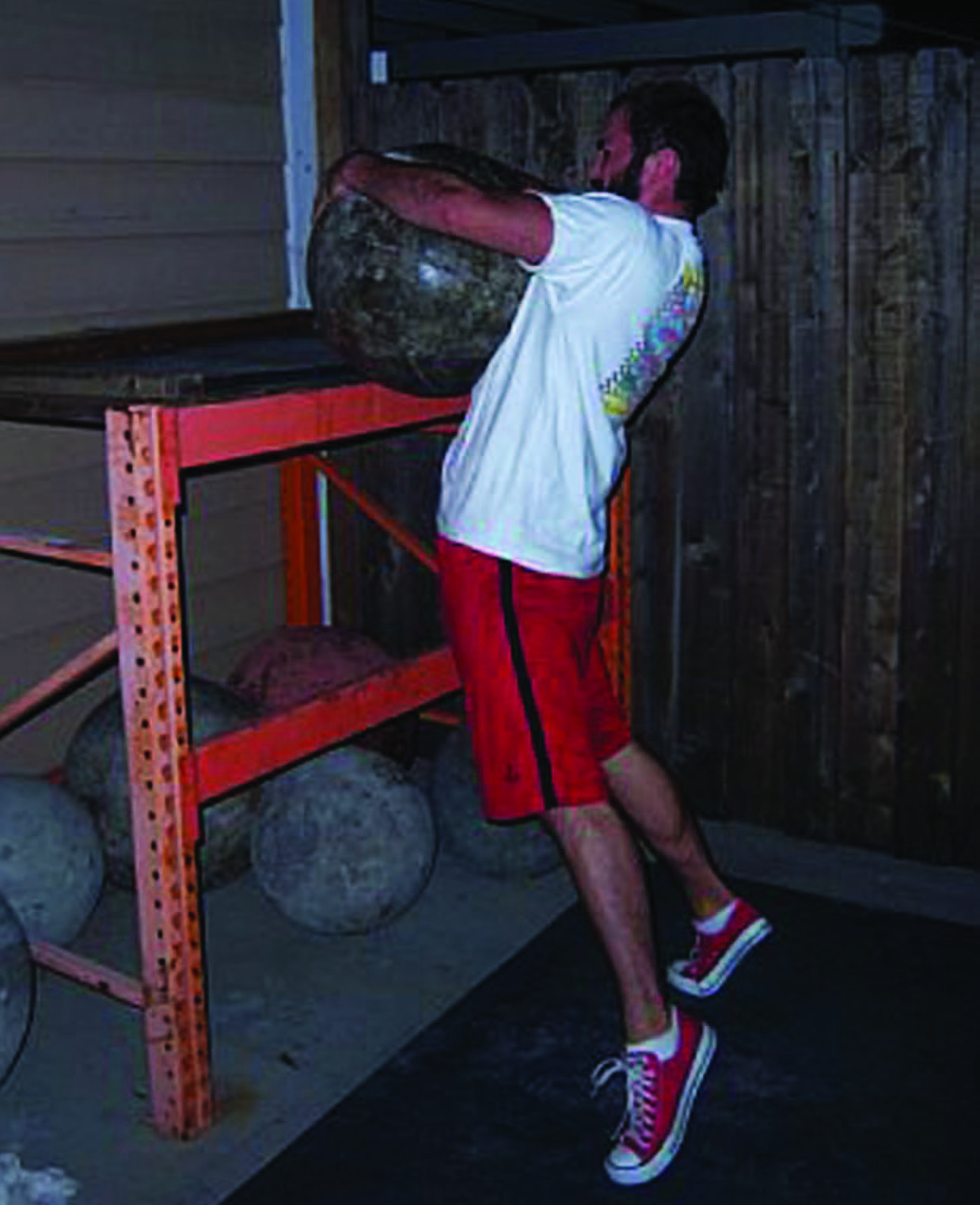

Many strongman athletes rely heavily on powerlifting models of strength training to develop their absolute strength. Doing so has bound them to sumo deadlifts, box squats and strict pressing. The ability to squat deep is a foreign concept to the majority of competitors, and it shows when they have difficulty getting into position to pick up objects that may be lower to the ground for carries. If you question your mobility, start with your ability to squat below parallel. If parallel is your limit, start working on that depth. Whether it’s an issue with your hips or ankles, it’s holding you back. Not only will developing the mobility to squat below parallel help you to pick up objects from the ground, in my experience the athlete that squats deep is generally far more athletic and powerful than the box squatter or parallel squatter.

Watching strongman athletes clean and press is downright disgusting much of the time. I’m willing to bet that many readers of this publication would throw up in their mouth a little after watching some clean and press for reps events in strongman contests. The problem is that many of the athletes begin in the sport after only practicing powerlifting or bad weightlifting, and when they are given an odd object, they assume their sloppy lifting is just par for the course. Maybe it is, but to continue with the golf analogy, you shouldn’t settle for par if you want to perform well. Whether it’s for max weight or max reps, athletes that know how use their hips and move through triple extension efficiently are going to have a leg up on those that simply muscle their way through-- both in contest numbers and in reduced training injuries.

Strict pressing heavy weights is a feat that deserves respect. It definitely has mine, as I have never been great at it. But when I see a strongman strict press something impressive, I can’t help but think of how much easier it could be if they simply jerked the weight. Many strongmen are shackled to the slow strict press, all because they never took the time to learn to jerk, or even push press well. A good jerk will move more weight and do it faster.

Tip #2: Move in All Directions

The common powerlifting background of many strongman athletes is once again evident when you watch them walk around between events with their toes out to the sides. This type of gait is going to destroy any sort of foot speed an athlete may have during carrying events. If you can point your toes straight ahead while you carry, it’s an advantage you may have over other competitors of all sizes that have to duck walk.

In addition to simply squatting below parallel, including more single leg and multi-directional work through out your training will improve the strength of the hip girdle as well as mobility. You can begin implementing traditional track warm ups like skips, shuffling, and carioca as well as band work and other dynamic warm ups to start. In addition, you can progressively include more training movements like split squats and single leg deadlifts into the accessory work of your strength program. All these things will help you improve your mobility, among other things, and help you carry all sorts of things a little bit quicker.

Tip #3: Improve Shoulder Mobility for Pressing

Overhead pressing in strongman events is most commonly done with a log, an axle or a dumbbell, but it can also include odd objects like kegs. Each of these objects has its own challenges and advantages, but mobility in the shoulders can play a huge role in how you go about cleaning and pressing each one.

The log is likely the easiest rack position due to neutral grip and bilateral loading/gripping, which allows for easier stabilization. Learning to breath effectively is likely the largest issue with a heavy log. We’ll discuss this later on.

When the axle is cleaned, it doesn’t need to sit in a full front squat rack position, but the ability to keep the bar close to the shoulders will allow the competitor to initiate the jerk or push press without losing energy due to excessive movement and adjustment of the rack position.

Circus dumbbells are most often push pressed from a side rack position. This requires a 3-step process for each lift. Clean, rotate the dumbbell out, then press. If the athlete develops the mobility and shoulder stability to rack the dumbbell in a neutral grip position, though, he or she can skip the rotational step and jerk the implement more effectively instead of push pressing. Saves time, saves energy.

Make sure you maintain the required mobility and stability to perform well in all of these lifts by not overspecializing in just one. Include plenty of upper body pulling movements like rows and face pulls as accessory work. Drills like wall slides, crawling patterns, and bottoms up kettlebell carries are great additions to warm ups and conditioning to maintain shoulder mobility and strengthen your ability to stabilize the scapula. These types of movements keep you pressing more weight faster, longer, and with less shoulder pain.

Tip #4: Practice Bracing and breathing

Most athletes competing have a good understanding of bracing when lifting and carrying, but many disregard breathing entirely and simply try to perform an entire event under the held breath of the Valsalva maneuver. Carrying objects like sandbags or Husafell Stones is done much faster if they’re carried high because it keeps the object out of the way of the legs, but this restricts your ability to expand your chest and breath. For this reason, athletes can improve endurance speed by simply practicing breathing from the diaphragm. Brace abdominally and practice simultaneously breathing with shallow breaths from the belly. While the tension in the midsection required to move big objects can restrict your ability to expand in the belly fully, practicing breathing with shallow breaths can keep gas in your tank when the weight of an object doesn’t allow you to expand your rib cage for air. Nobody expects a strongman to breath like a yoga guru, but that doesn’t mean it wouldn’t help.

Tip #5: If you can do it faster, it doesn’t matter if you can do heavier

In a strongman competition, there are occasionally max weight lifts that favor the athlete with the greatest absolute strength. These are typically only one of five events in a full contest, though. What matters most of the time are the reps and times in bread and butter events like atlas stones, max repetitions of clean and press, tire flipping, or carrying and dragging things. It is not always the athlete with the biggest training numbers that takes the most points in the event. If you can hit numbers above what is necessary for an upcoming competition, it will serve you well to begin focusing on your speed and conditioning with the specific contest weights and implements. What good is a 300-lb. overhead axle press if you can only clean and jerk 255 twice in a minute? How impressive is that 800-lb. yoke walk if it takes you the full allotted minute to move 700-lb. the contest length? Don’t neglect your max effort movements, but take time to dial things back. For example, focus on developing your foot speed with lighter carries for multiple sets, or going through the motions of a continental clean faster with sub-max loads. Not only will your speed improve, the additional work will help you develop the greater work capacity to train more and recover faster in contests. The SAID principle tells us that if we want to be faster, we have to train faster, not just heavier all the time. It’s surprising how often athletes won’t put their ego aside to work on something they are less comfortable with.

Tip #6: Plan for Recovery and Manage Max Effort Work

While max effort work is important, too much can quickly lead to overtraining and injury. Adjusting training loads and rep ranges is necessary to keep the athlete healthy over the course of a career. This can be done well with either a block program adjusting the intensities and volumes in a wave, or by following a model similar to Westside that includes both max effort and dynamic effort work each week. Athletes in lighter weight classes may also want to consider their stature when balancing volume and intensity during later phases of a training block or on max effort days. I have found that great progress can still be made hitting max effort numbers over 95% for only 1-3 sets. Larger athletes and others utilizing certain “technologies” may be better suited to training both high volumes and intensities simultaneously, but less enhanced or smaller athletes may need to keep the volume in check at higher loads and intensities

Tip #7: Work All Your Energy Systems

Despite the short duration of events in a contest, there are important reasons to develop all energy systems to some extent. It is particularly shortsighted to think strongmen only need to develop creatine phosphate energy systems. Any event lasting the full span of the minute will heavily tax other anaerobic energy systems in addition to creatine phosphate systems. You can make use of an interval timer and structure work periods from 20 seconds to three-minute bouts, using heavy sled drags, basic carries or combinations of events. However, the aerobic system is also going to play a huge role in how the athlete recovers between events. Including some walking or hiking on off days or between high-intensity bouts should benefit the athlete by improving recovery as well as energy systems, all with little additional stress. At the end of a contest, it boils down to only about five to eight minutes of exhaustive work over the course of an afternoon, but a decent set of lungs and good aerobic capacity goes a long way in making sure that an individual is fully recovered between each of the events. Energy systems are never working completely independent of the others.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve ever thought you wanted to compete in strongman, you’ll want to start with the same basic strength movements you might teach any athlete: squats, deadlifts, cleans, presses, rows, and carries. These basic movements really are the foundation of strength needed for participation. But when you want to go from simply participating to being competitive or even winning, you need to have a little extra something. You have to be able to perform the lifts not just with heavy weight, but with speed and efficiency. You need to move quickly and under load. Neglecting proper technique and good mobility, or not properly planning your training, will leave you in the middle of the pack at best, and potentially injured or in last place at worst. If you put your ego aside and implement these tips into your training, you’ll avoid some of the pitfalls that so many have fallen victim to in their strongman training. Good luck, and maybe I’ll see you around.

When we look at the best in the sport, like Brian Shaw, Derek Poundstone, or Mariusz Pudzianowski, not only are these athletes incredibly strong, but they also move surprisingly well. This is not reflected in most strongman competitions at the amateur level, though. Many of the amateur competitors have a training background rooted solely in powerlifting and often move in a way that shows their neglect of other athletic qualities. Smaller trainees and athletes will find that they are far more competitive with the big guys if they take the time to learn how to move well and perform lifts efficiently, as opposed to neglecting anything outside powerlifting, as so many do. Additionally, the big fellas would also be served well to take the following considerations to heart in their training and practice.

Strongman is more multidimensional than just absolute strength. My success in the sport has more to do with my speed and mobility than my numbers in the weight room. I am certainly not the strongest in the sense of pounds on the bar in the weight room, but by lifting and moving more efficiently than other competitors, I have been able to go further in the sport. The following considerations reflect some training aspects that can help those looking to begin or continue with strongman perform better by training to be more efficient as athletes.

Tip #1: Learn the Basic Moves

Many strongman athletes rely heavily on powerlifting models of strength training to develop their absolute strength. Doing so has bound them to sumo deadlifts, box squats and strict pressing. The ability to squat deep is a foreign concept to the majority of competitors, and it shows when they have difficulty getting into position to pick up objects that may be lower to the ground for carries. If you question your mobility, start with your ability to squat below parallel. If parallel is your limit, start working on that depth. Whether it’s an issue with your hips or ankles, it’s holding you back. Not only will developing the mobility to squat below parallel help you to pick up objects from the ground, in my experience the athlete that squats deep is generally far more athletic and powerful than the box squatter or parallel squatter.

Watching strongman athletes clean and press is downright disgusting much of the time. I’m willing to bet that many readers of this publication would throw up in their mouth a little after watching some clean and press for reps events in strongman contests. The problem is that many of the athletes begin in the sport after only practicing powerlifting or bad weightlifting, and when they are given an odd object, they assume their sloppy lifting is just par for the course. Maybe it is, but to continue with the golf analogy, you shouldn’t settle for par if you want to perform well. Whether it’s for max weight or max reps, athletes that know how use their hips and move through triple extension efficiently are going to have a leg up on those that simply muscle their way through-- both in contest numbers and in reduced training injuries.

Strict pressing heavy weights is a feat that deserves respect. It definitely has mine, as I have never been great at it. But when I see a strongman strict press something impressive, I can’t help but think of how much easier it could be if they simply jerked the weight. Many strongmen are shackled to the slow strict press, all because they never took the time to learn to jerk, or even push press well. A good jerk will move more weight and do it faster.

Tip #2: Move in All Directions

The common powerlifting background of many strongman athletes is once again evident when you watch them walk around between events with their toes out to the sides. This type of gait is going to destroy any sort of foot speed an athlete may have during carrying events. If you can point your toes straight ahead while you carry, it’s an advantage you may have over other competitors of all sizes that have to duck walk.

In addition to simply squatting below parallel, including more single leg and multi-directional work through out your training will improve the strength of the hip girdle as well as mobility. You can begin implementing traditional track warm ups like skips, shuffling, and carioca as well as band work and other dynamic warm ups to start. In addition, you can progressively include more training movements like split squats and single leg deadlifts into the accessory work of your strength program. All these things will help you improve your mobility, among other things, and help you carry all sorts of things a little bit quicker.

Tip #3: Improve Shoulder Mobility for Pressing

Overhead pressing in strongman events is most commonly done with a log, an axle or a dumbbell, but it can also include odd objects like kegs. Each of these objects has its own challenges and advantages, but mobility in the shoulders can play a huge role in how you go about cleaning and pressing each one.

The log is likely the easiest rack position due to neutral grip and bilateral loading/gripping, which allows for easier stabilization. Learning to breath effectively is likely the largest issue with a heavy log. We’ll discuss this later on.

When the axle is cleaned, it doesn’t need to sit in a full front squat rack position, but the ability to keep the bar close to the shoulders will allow the competitor to initiate the jerk or push press without losing energy due to excessive movement and adjustment of the rack position.

Circus dumbbells are most often push pressed from a side rack position. This requires a 3-step process for each lift. Clean, rotate the dumbbell out, then press. If the athlete develops the mobility and shoulder stability to rack the dumbbell in a neutral grip position, though, he or she can skip the rotational step and jerk the implement more effectively instead of push pressing. Saves time, saves energy.

Make sure you maintain the required mobility and stability to perform well in all of these lifts by not overspecializing in just one. Include plenty of upper body pulling movements like rows and face pulls as accessory work. Drills like wall slides, crawling patterns, and bottoms up kettlebell carries are great additions to warm ups and conditioning to maintain shoulder mobility and strengthen your ability to stabilize the scapula. These types of movements keep you pressing more weight faster, longer, and with less shoulder pain.

Tip #4: Practice Bracing and breathing

Most athletes competing have a good understanding of bracing when lifting and carrying, but many disregard breathing entirely and simply try to perform an entire event under the held breath of the Valsalva maneuver. Carrying objects like sandbags or Husafell Stones is done much faster if they’re carried high because it keeps the object out of the way of the legs, but this restricts your ability to expand your chest and breath. For this reason, athletes can improve endurance speed by simply practicing breathing from the diaphragm. Brace abdominally and practice simultaneously breathing with shallow breaths from the belly. While the tension in the midsection required to move big objects can restrict your ability to expand in the belly fully, practicing breathing with shallow breaths can keep gas in your tank when the weight of an object doesn’t allow you to expand your rib cage for air. Nobody expects a strongman to breath like a yoga guru, but that doesn’t mean it wouldn’t help.

Tip #5: If you can do it faster, it doesn’t matter if you can do heavier

In a strongman competition, there are occasionally max weight lifts that favor the athlete with the greatest absolute strength. These are typically only one of five events in a full contest, though. What matters most of the time are the reps and times in bread and butter events like atlas stones, max repetitions of clean and press, tire flipping, or carrying and dragging things. It is not always the athlete with the biggest training numbers that takes the most points in the event. If you can hit numbers above what is necessary for an upcoming competition, it will serve you well to begin focusing on your speed and conditioning with the specific contest weights and implements. What good is a 300-lb. overhead axle press if you can only clean and jerk 255 twice in a minute? How impressive is that 800-lb. yoke walk if it takes you the full allotted minute to move 700-lb. the contest length? Don’t neglect your max effort movements, but take time to dial things back. For example, focus on developing your foot speed with lighter carries for multiple sets, or going through the motions of a continental clean faster with sub-max loads. Not only will your speed improve, the additional work will help you develop the greater work capacity to train more and recover faster in contests. The SAID principle tells us that if we want to be faster, we have to train faster, not just heavier all the time. It’s surprising how often athletes won’t put their ego aside to work on something they are less comfortable with.

Tip #6: Plan for Recovery and Manage Max Effort Work

While max effort work is important, too much can quickly lead to overtraining and injury. Adjusting training loads and rep ranges is necessary to keep the athlete healthy over the course of a career. This can be done well with either a block program adjusting the intensities and volumes in a wave, or by following a model similar to Westside that includes both max effort and dynamic effort work each week. Athletes in lighter weight classes may also want to consider their stature when balancing volume and intensity during later phases of a training block or on max effort days. I have found that great progress can still be made hitting max effort numbers over 95% for only 1-3 sets. Larger athletes and others utilizing certain “technologies” may be better suited to training both high volumes and intensities simultaneously, but less enhanced or smaller athletes may need to keep the volume in check at higher loads and intensities

Tip #7: Work All Your Energy Systems

Despite the short duration of events in a contest, there are important reasons to develop all energy systems to some extent. It is particularly shortsighted to think strongmen only need to develop creatine phosphate energy systems. Any event lasting the full span of the minute will heavily tax other anaerobic energy systems in addition to creatine phosphate systems. You can make use of an interval timer and structure work periods from 20 seconds to three-minute bouts, using heavy sled drags, basic carries or combinations of events. However, the aerobic system is also going to play a huge role in how the athlete recovers between events. Including some walking or hiking on off days or between high-intensity bouts should benefit the athlete by improving recovery as well as energy systems, all with little additional stress. At the end of a contest, it boils down to only about five to eight minutes of exhaustive work over the course of an afternoon, but a decent set of lungs and good aerobic capacity goes a long way in making sure that an individual is fully recovered between each of the events. Energy systems are never working completely independent of the others.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve ever thought you wanted to compete in strongman, you’ll want to start with the same basic strength movements you might teach any athlete: squats, deadlifts, cleans, presses, rows, and carries. These basic movements really are the foundation of strength needed for participation. But when you want to go from simply participating to being competitive or even winning, you need to have a little extra something. You have to be able to perform the lifts not just with heavy weight, but with speed and efficiency. You need to move quickly and under load. Neglecting proper technique and good mobility, or not properly planning your training, will leave you in the middle of the pack at best, and potentially injured or in last place at worst. If you put your ego aside and implement these tips into your training, you’ll avoid some of the pitfalls that so many have fallen victim to in their strongman training. Good luck, and maybe I’ll see you around.

|

Brian Tabor has been competing in amateur strongman for over 4 years, and won the North American Strongman 175-lb. National Championship in 2010. He is the owner of Strong Made Simple in San Diego, Calif., where he trains a variety of clients for strength, fitness, and health. Additionally, Brian is a MovNat Certification Team Instructor and teaches workshops focusing on natural movement patterns throughout the U.S. He moves like a spider monkey, lifts like King Kong, and reads like Dr. Zaius. You can find more from Brian at his website, http://www.strongmadesimple.com, on facebook, and on twitter—or e-mail him at brian@strongmadesimple.com. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date